Mind Games

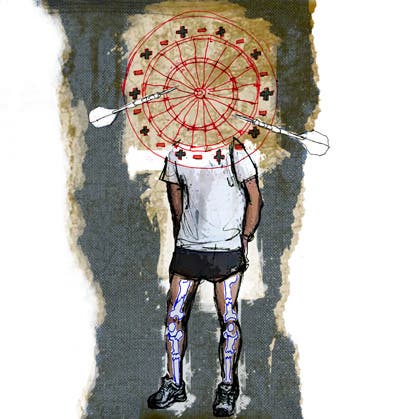

Injury got you down? it’s all in your head

Last summer, just four weeks before the Pumpkinman Club Championship triathlon in Las Vegas, Nevada, I developed a painful stress fracture in my left foot. As a professional coach, I know this type of injury typically takes six to 10 weeks to heal, which means no running. Though I felt frustrated, my body benefited from the extra rest and I ended up savoring the break from training for swimming, biking and running.

As a result, on race day I was mentally sharp and rested. Transitioning from the bike to the run, my legs felt fresh, feet quick and stride fluid. Before I knew it, I’d scored my fastest run split of the season. Seeing the injury as an opportunity rather than a setback allowed me to heal quickly, enjoy a mentally rejuvenating pre-race period and have a solid performance.

Injuries stink, but choosing to convert them into an empowering experience gets you back on the trails sooner.

The Psych Factor

Sport psychologists studying the relationship between injury and emotion have identified four factors that determine how athletes cope with injury: personality, history, outlook and coping style.

Organized, controlling and proactive personality types (“type A” people) are more likely to approach rehabilitation with strategy and discipline and stay motivated during treatment. However, those feeling victimized and not in control (viewing the injury as punishment or infliction from an outside source) tend to stray from treatment, ignore the problem, or rush back to regular activity too soon.

Those who have suffered a long layoff due to injury in the past are more prone to concede to another lengthy layoff, even if it’s not necessary this time.

And outlook tends to dictate coping style. Pessimists enhance their distress by focusing on what they’ve lost in terms of fitness, race goals or athletic part of their identity. Optimists who view injury as part of the athletic journey generally heal faster by committing more readily to the rehabilitative process with focus and determination.

The Control Factor

Emotional reactions to injury may begin with denial that progresses to anger, leading to rationalization as a way to downplay the injury’s severity. Examples of rationalization strategies are experimenting with brief rest periods or promising to stretch daily without addressing the injury’s root cause. When such avoidance tactics fail, depression and worry can ensue. Instead, examine your perception of the situation by asking questions such as, “Is this injury going to drastically change my life? What does my body need to keep performing?” and, “What does this injury free me to do with my time?”

These questions put the injury into context and open your eyes to new lessons. Maybe you need to train less or differently. Perhaps your gait needs adjustment (through form drills, orthotics or different shoes) or you have a muscle imbalance.

The Action Factor

Once you’ve established a positive mindset, choose an appropriate course of action. Rather than letting injury be an excuse for inaction, assemble a team of professionals—a sport psychologist, doctor and physical therapist—to help you convert your passion for training into a passion for rehabilitation.

The Time Factor

Attach a realistic time frame to your recovery plan in order to stay motivated and on track for success. While a doctor or physical therapist can determine which physical improvements are possible within a certain period, a sport psychologist helps you maintain a positive mindset and celebrate intermediate achievements along the path to complete recovery.

As a bonus, injury rewards you the gift of extra time to spend with family and friends, on your career, personal growth or new hobbies, often leading to a more balanced and relaxed lifestyle.

Back in the Running: Returning to the trails after time off

Having a positive outlook during your layoff will set you up for a success once you’re healed and get you the green light from your physician or physical therapist to resume training.

- To prepare your body for the stress of running again, begin with two weeks of low-impact cross training. During this time, you should be able to walk briskly, bike or swim without pain.

- When you resume running, begin with only 50 percent of your pre-injury mileage at half your usual pace. Or alternate intervals of running for two to five minutes with walking for an equal amount of time.

- Though it’s tempting to ramp up your mileage and pace, do so by no more than 10 percent per week. But avoid increasing mileage, frequency and speed simultaneously. Instead, boost the length of your long run one week, and intensity of shorter runs the following week.

Ashley Mosher Naegele, founder of Mindful Sports, uses self discovery to enhance the performance of athletes of all levels. She is a former U.S. national swim-team member and has a Masters in Sport Psychology and Kinesiology from the University of Minnesota.