The Mending of Dave Mackey

After a horrific mountain-running accident, one of the sport’s humblest champions wonders if he’ll ever run again

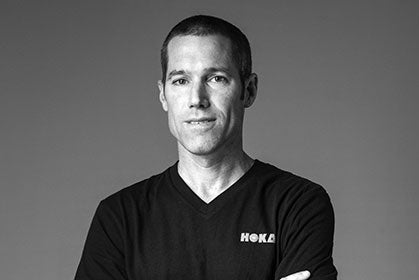

Photo by Robert Timko.

Ed’s note, October 2016: After more than a year of surgeries and lingering pain, Mackey announced his decision to have his left leg amputated below the knee. “This would mean the freedom, if I choose it, to walk the kids to school without a thought, ski, run in 6-8 weeks, compete in races again,” he wrote about the decision on Facebook this month.

The morning of May 23, 2015, was a murky one in Boulder, Colorado. A light drizzle doused the area in the hours before daylight, and a low cloud cover obscured the mountains that border the city to the west.

Boulder was experiencing its soggiest spring in 20 years. Considerable rain—plus several bouts of late-season snowfall and freezing temperatures atop the nearby peaks—made Boulder’s trails uncharacteristically damp, loose and lush with vegetation.

As he left his house for what he thought would be a familiar run up and over Boulder’s highest summits, Dave Mackey posted a photo of the cloud-shrouded mountains on Instagram and Facebook.

“Sigh. Heading to the 8,500’ office. 7 days a week. Tough job. Someone’s gotta do it,” Mackey posted with his characteristic dry wit.

Although he wasn’t planning anything epic for that day, he was eager to grind out a stout run with a good amount of vertical. He was feeling good about his training; his legs had recovered from his 12th-place finish at the menacingly tough six-day, 156-mile Marathon des Sables in Morocco in April, and his next race, the Western States Endurance Run, was still about a month away. He wasn’t about to let the weather slow him down.

For the past year or so, Mackey, 45, has worked as an emergency-room physician assistant at a hospital on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in southwestern South Dakota. Although it’s a five-hour drive from Boulder, the pay is good and he’s able to work in blocks—on for two weeks, off for two weeks.

With four days until he had to head back for his next shift, Mackey was excited to be in Boulder, partly to run his favorite trails as much as possible, but much more so to spend time with his family. School was out, both for his young children, 7-year-old Ava and 5-year-old Connor, as well as his wife, Ellen, a second-grade teacher. Plus, it was Memorial Day weekend in Boulder, which meant hanging out at the Boulder Creek Festival, running or watching the Bolder Boulder 10K road race and attending numerous barbecues and other events.

Mackey didn’t intend on running alone that morning, but none of his usual training partners were able to join, so off he went. He left his house in South Boulder just after 7:15 a.m., planning to run up 8,549-foot South Boulder Peak and 8,461-foot Bear Peak and, depending on how he felt, maybe 8,144-foot Green Mountain, too.

“It was going to be a pretty straightforward run that I’ve done hundreds of times,” he says. “But it didn’t quite turn out that way.”

Mackey in the Fisher Towers, Utah. Photo by Ross Comer.

For the past decade and a half, Dave Mackey has been one of America’s premier trail runners, yet there is a good chance you haven’t heard much about him (perhaps until recently). Although he’s been sponsored by various shoe and gear brands, he’s flown under the radar because he doesn’t talk much about his accomplishments or pimp his race results. Even in the age of social media—when everyone posts race reports, gear company shout-outs and look-at-me photos ad nauseam—Mackey is subtle and painstakingly modest.

It’s one of the things that makes him so endearing, a guy many who know him hold up on a lofty pedestal. To them, he’s not only one of the best mountain athletes they know, but one of the most genuine people they’ve ever met.

Mackey will be the first to admit he doesn’t have the all-out speed of Max King, the 100-mile legacy of Karl Meltzer or the prolific racing ability of Mike Wardian. Nor does he possess the social-media savvy of Sage Canaday or the international following of Anton Krupicka or Scott Jurek. What he does have, though, is a deep toolbox of real mountain skills, most notably a huge aerobic engine, amazing strength and body control on off-camber terrain and, perhaps his biggest athletic gift, calmness in the face of adversity.

“The thing about Dave is that he has an amazing ability to turn himself inside out, to go into the well in every race and just grind it out when it’s difficult,” says Bob Africa, a longtime friend and training partner who narrowly beat Mackey in the five-event Leadman endurance competition last summer. “He’s ridiculously strong almost every time out there, and yet, at the end of the day, it’s not about him.”

When you look at Mackey’s body of work over the past 15 years or so—a diverse collection of ultra victories, course records and multisport podium results—it compares favorably with any of those aforementioned stars. During that span, he has twice won the Montrail Ultra Cup (in 2004 and 2011); won national championships for 50K, 50-mile and 100K distances; and held the Rim-to-Rim-to-Rim record for running 42 miles across the Grand Canyon and back.

He’s won many of the country’s most competitive trail ultras, including the American River 50-miler, Miwok 100K, Way to Cool 50K, JFK 50, Zane Grey Highline Trail 50-miler and Mountain Masochist 50-miler, setting numerous course records along the way. He was also second to Matt Carpenter at the 2001 Pikes Peak Marathon and runner-up to Jurek at the 2004 Western States 100. And he’s done it all in a very understated way.

“You really have to drag it out of him,” says Jeff Valliere, another of Mackey’s training partners. “When he gets back from a race weekend and you ask him how it went, his typical response is, ‘Yeah, it went pretty well,’ and if you don’t keep asking questions, you might not know until you look it up that he won and set a new course record.”

Mackey hasn’t skipped a beat since turning 40, even as ultrarunning has gotten younger and more competitive. He was eighth at The North Face Endurance Challenge 50-mile championship in 2013, fifth in last year’s Leadville 100 and second at the Black Canyon 100K in February.

What makes him most notable as an athlete—especially in Boulder—is his versatility. Aside from his trail-running prowess, he’s a strong mountain biker, telemark skier and rock climber, regularly ascending expert-level 5.12 rock faces. He’s perhaps most adept at scrambling—using his hands and feet to move dynamically over steep planes of rocks and scree. In addition to the trail records he holds around Boulder, he’s set new marks for scrambling up and down the Flatirons—the massive, iconic rock faces that are so tied to Boulder’s identity as a mountain-sports hub—and has won several informal “Tour de Flatirons” scrambling races.

“As good as he is as a runner, he’s an expert at scrambling, one of the best in the world,” says Boulder trail runner and climber Bill Wright, who heads up the club that organizes the scrambling events.

And he’s even stronger on the way down. Mackey running downhill is a sight to behold, a mix of speed, power and complete control in a near-harmonious flow state.

“He can just fly through the downhills,” says four-time Pikes Peak Marathon champion Danelle Ballengee, a former adventure-racing teammate of Mackey’s in the mid-2000s. “It’s amazing how good he is. He’s just so in his element in situations like that.”

After shattering his leg during a fall, Mackey lay stranded on a precarious ledge. It took some two dozen volunteers to safely lower him down the mountain. Photo by Bill Wright

Their twin summits piercing the sky, South Boulder Peak and Bear Peak, along with nearby Green Mountain, define Boulder’s dramatic western skyline. For years, they’ve been beacons for all to behold and pursue—hikers and tourists, artists and sightseers, mountain climbers and trail runners. And as hardscrabble mountain ultrarunning began to grow in the 1990s and eventually mushroom in popularity in the past 10 years, the trails up those peaks became testing grounds for hundreds of top-tier trail runners wanting to prove their mettle.

On his May 23rd outing, wearing running shorts and a tech tee, Mackey ran along Mesa Trail and then up Shadow Canyon toward South Boulder Peak at about 8:20 a.m. After reaching its summit, he headed along the saddle en route to Bear Peak, just a few hundred yards away, passing his friend Paul Gross along the way.

Gross, a 50-year-old attorney in Boulder, caught the trail-running bug a dozen years ago. He originally met Mackey when his oldest son was a student in Ellen Mackey’s first-grade class, but he’d never trained with him because, well, “for most of us, Dave is just in a different league.” Still, Gross has gleaned inspiration from Mackey over the years, from running Leadville in 2004 to training for his fourth Hardrock 100 this spring.

As they greeted each other, Gross, who had already summited Bear Peak, said he was planning to tag the top of South Boulder Peak, then pass Bear again on his way back down to the trailhead. After they parted ways, Mackey scrambled up the south side of Bear’s summit. He took a moment to catch his breath, drink some water and glance at his watch before opting to scramble down the west side of the peak—not the common route for hikers, but a way Mackey and many others often take.

Then, suddenly, at about 8:45 a.m., a rock dislodged from under him. “I’ve stepped on that same rock hundreds of times,” Mackey would say a day later from a hospital room. “This time it just gave way.”

What ensued was a violent, cascading fall that sent him tumbling 20 or 30 feet, bouncing off rocks and small branches, before he came to rest on a precarious ledge. During the fall, he badly banged his lower left leg against a rock, causing it to explode into a severe compound fracture—an injury that could have proven life-threatening if he had knocked himself out or severed an artery on the way down. The rock that had dislodged—estimated at 150 to 300 pounds—rolled to a stop on his injured leg, making matters worse.

Shouting for help, Mackey leaned forward and tried to push the rock from his leg but could not. He continued screaming for Gross, who he hoped would be within earshot soon.

“It was kind of an odd sound,” said Gross, who was below Bear Peak at the time. “He was well above where I was going. I couldn’t hear it that well, but I heard something, so I went that up that way.”

Within a few moments, Gross found Mackey and, while trying to comfort him, called 911. Emergency dispatchers notified the Boulder County Sheriff’s Department and sent out an alert to Rocky Mountain Rescue, a Boulder-based volunteer group trained to rescue people from traumatic mountain accidents.

Gross tried to reach Mackey’s wife, Ellen, but could not. He called Valliere, Mackey’s sometime training partner, who was at home in nearby Louisville. Valliere soon reached Ellen and told her what he knew.

Then he called a few running and climbing friends he thought might already be in the mountains and somehow be able to help. As luck would have it, Bill Wright had hiked up Shadow Canyon with a friend that morning, just after Mackey, and was on his way back down when he got the call. He quickly reversed direction and charged up Bear Peak.

Photo by Bill Wright

In the meantime, Gross struggled to roll the rock off Mackey’s leg, knowing he risked causing greater injury and even knocking Mackey further down the mountain. When he finally pried it off with a small branch, he saw “a horrendous compound fracture”—splintered bone fragments were visible in the bloody wound, and most of the muscle in his calf was exposed. Despite writhing in pain, Mackey, utilizing his medical training and on-the-job emergency-room experience, instructed Gross to straighten and realign his leg in order to relax the muscles, take pressure off the bones and reduce pain.

“I was nervous and apprehensive, but he was coherent and I knew he was a PA, so I did what he said,” Gross recalls. “I wound up holding his leg for more than an hour and a half until the rescue team arrived.”

About 15 minutes after Gross showed up, Meg Fibbe, a trail runner Mackey had passed between the two peaks, arrived to help, followed by two hikers. As Gross continued to hold his leg, first Fibbe then one of the hikers, John Christie, supported Mackey’s upper body on the ledge, while several other people gave their clothes to Mackey and the first responders so they could stay warm in the damp, 45-degree weather. That’s about the time Wright arrived.

“I don’t know how he wasn’t bleeding to death,” Wright says. “When you have that kind of an injury, how major arteries or veins weren’t cut is astounding. At that point, I was worried about him living.”

While the first responders stayed at Mackey’s side, Wright and others went down to help Rocky Mountain Rescue personnel carry equipment up the mountain. Eventually, a team of more than two dozen Rocky Mountain Rescue volunteers—including two emergency-room doctors—helped stabilize Mackey and safely lowered him down a scree field on a fixed rope. Then they used a wheeled litter to get him down a trail on the back side of the mountain, where Ellen was waiting along with an ambulance and other fire-rescue personnel. Although he was medicated, Mackey was awake as the rescue group slowly and carefully brought him down the mountain.

“I was looking up and could see trees above me, but I didn’t really know exactly where I was until we got close to the ambulance,” he says. “It was a bit surreal. At that point, I was just happy to be in good hands.”

Photo by Bill Wright

When Mackey entered Boulder Community Foothills Hospital, there was serious concern he might lose his leg. A team of doctors delicately pieced together his broken fibula and shattered tibia with a metal rod and several plates and screws. The leg went together pretty well, but because he had lost so much skin and soft tissue, his ability to heal was unclear.

A few days after being transferred to Denver Health Medical Center, Mackey underwent a procedure known as a gastroc flap, in which a portion of muscle was removed from his left calf and placed over the tibia on the front side of his shin to promote blood flow to the area. Doctors also removed a large layer of skin from his left thigh to help cover the exposed bone and soft tissue in his lower left leg, the first of two skin-graft surgeries he would undergo.

But he still wasn’t out of the woods. Within a few days, Mackey became lightheaded and feverish and, sensing he had an infection, doctors decided to disassemble the original orthopedic work—removing the rod, plates and screws—to clean out the injury. While they were inside the injured leg, they realized some of the bone and muscle tissue still wasn’t growing as well as it should. They removed a small piece of his tibia bone and replaced it with a synthetic spacer laced with medications. Then they reassembled his leg with new hardware, and added a metal frame called an external fixator, or X-fix.

Three days later, during a seven-hour surgery on June 5, doctors harvested a flap of muscle from one of his left quad muscles and inserted it over the injured tibia. After that, they performed another skin graft—this time removing skin from his right thigh and placing it over the bone in his lower left leg. He spent parts of the next three days in the intensive care unit, in a room heated to 88 degrees for the first 40 hours to ensure optimal healing.

On June 10, he underwent a seventh surgery, during which doctors went back into the injured leg to once again clean out the wound, determine if the soft tissue and bone had progressed and adjust the X-fix. He will likely undergo another surgery in late August to remove the spacer in his left leg and replace it with bone material harvested from his left femur.

Finally, on the evening of June 13—a full three weeks after the accident—Mackey returned home from what he thought was going to be a fairly routine run over some of his favorite Boulder trails.

Photo by Randall Levensaler.

There has been an amazing outpouring of support for Mackey, both locally in Boulder and via the Internet. Runners from around the country and the world have sent well wishes his way, dedicated races to him, donated thousands of dollars to cover his medical costs and reminded him that he’s not alone in what figures to be a long road to recovery. Videographer Billy Yang even created a compilation of short messages from dozens of ultrarunners and posted it on Facebook.

Although not usually a serial poster, Mackey reached out several times on Facebook to thank friends and fellow runners for their support.

“What I am going through though is nothing compared to millions of peoples’ lives every day,” he wrote in a Facebook post on June 7. “Some friends have told me of their struggles and accidents which helps immensely. Thank you again to Ellen, close friends and my kids for pulling me through. Don’t take for granted what you have, value it.”

Upon his return home, Mackey was housebound and extremely limited in his mobility. While staying off his feet in the hospital, he had lost considerable strength in his good leg, and his prescribed rehab of crutching around the house for 10 minutes at a time was exhausting. But he has maintained his strong resolve and positive mindset, reminding himself constantly that he was lucky to be alive and in such good care, with his family and friends close by.

Mackey has no idea if he’ll be able to run again. It’s an awkward and perhaps unfair question to ask so soon, but it’s certainly one that’s been on everyone’s mind—especially his own. If all goes well, he’ll spend the rest of the summer recovering from surgeries and regaining enough strength to walk again. No matter what, he knows this accident will forever impact his life, but he also knows it could have gone a lot worse had he lost consciousness during the fall or ruptured an artery, or if doctors had ultimately been forced to amputate his leg.

No one is betting against him running again—but, for the time being, most are just happy he’s alive. Mackey himself has been optimistic that in a year he might be running trails again.

“I doubt I’ll be doing ultras at that point, but just getting out there running on the trails would be a good goal,” he says. “I just can’t see myself not running again.”

Brian Metzler was the founding editor of Trail Runner and is now the editor in chief of Competitor. He and Dave Mackey once did 12 different sports in 12 hours as part of a multisport training day. This article originally appeared in our September 2015 issue.