New perk! Get after it with local recommendations just for you. Discover nearby events, routes out your door, and hidden gems when you sign up for the Local Running Drop.

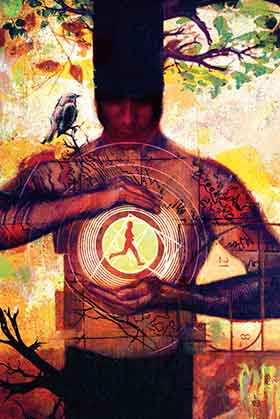

Illustration by Jeremy Collins

This article originally appeared in our April 2008 issue.

Accomplished ultrarunner Darcy Africa is hardly the type to sit still for long. But before she makes her way to the start line, she takes a load off to meditate. “It calms my mind and nerves in anticipation of the race,” says Africa. She must be onto something. Africa not only won the Cascade Crest 100 Mile Endurance Run and the Big Horn Mountain 100 last summer, but she also blew away both women’s course records by hours.

Contrary to popular belief, meditation is not sitting and doing nothing. “Don’t be fooled,” says Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, the spiritual director of Shambhala Buddhism who recently ran the Chicago Marathon in 3 hours30 minutes. “If you are meditating correctly,you are engaging the most important aspect of who you are: the mind.”Researchers have found that even small doses of daily meditation may improve attention, lower blood pressure, reduce pain and ward off anxiety and stress. But can slowing down for sitting meditation actually help you speed up for a trail run? “They can enhance each other,” says Africa, who, like me, attended a Buddhist program called Running with the Mind of Meditation at the Shambhala Mountain Center in Red Feather Lakes, Colorado.

Meditating on the Run

Although sitting meditation is important brain training, you can conceivably meditate while you’re on the move. “Naturally through running there’s a certain amount of environmental meditation,” says Rinpoche. “You pay attention to breathing, your feet. In order to pay attention, your mind has to leave other topics and come to something.” Before I attended the Shambhala program last summer, I thought running was my meditation. But I usually meant that I let my mind wander about on a run—mentally resolving conflicts with friends, imagining ways to tell off a difficult boss or brainstorming creative ideas. In other words, my mind went just about everywhere except the run. Instead, sitting or running meditation takes regular and disciplined practice to truly synchronize body and mind, to bring them both into the present moment, and, ultimately, to put them to use for a particular purpose or goal.

“The mind is the leading edge of whatever you want to do,” says Rinpoche. “Those who run know that after you’ve gotten used to physical activity, you’re working with your mind.” For example, running to the top of your nemesis hill often isn’t a matter of fitness but mental toughness.

Meditation can help you control distracting or debilitating thoughts, so they no longer get in the way. At one point during the Cascade Crest race, Africa got off route for about 45 minutes due to a mismarked course. Although she lost her way physically, she stayed in the race mentally enough to place first despite the setback. “Meditation helps me to let go of the thoughts that consume me and to be in the moment,” says Africa, who also usually meditates at the end of her once-per week yoga practice.

For Jon Pratt, who helps organize the running and meditation workshop at Shambhala Mountain Center, meditation helped him work through injuries, such as hamstring issues. “I found that my mind can be a friend,” Pratt says. “I’ve become more aware of how I’m running. Rather than trying to power through a run, I start to relax and discover how to run properly.”

Quality of Life

But cyclist and runner Eric Cech, who trained with Rinpoche for the Chicago Marathon, isn’t sure that his regular meditation practice over the past four years has necessarily made a difference in his race PRs. “But it has helped my life,” Cech says. “I’m better able to respond to things that come up in my life.” And maybe that’s the point—not to become better runners or better meditators, though those are worthy outcomes, but to engage in the world, no matter what you do. “Through meditation, you train your mind to come back to the here and now, which is really all you have,” says Pratt. “Then, you find joy in activities, like running.”

How to Meditate

At first, meditation may seem difficult. Be forgiving of your wandering thoughts. Don’t be afraid to move after a few minutes. Rotate your neck. Adjust your legs. But try to be consistent in your practice. You’ll reap more benefits if you meditate every day for short periods—even five or 10 minutes— than if you sit for longer periods just one or two days a week.

Posture. Sit cross-legged on a pillow or cushion (or in a chair with feet flat on floor). Imagine a string attached to the top of your head pulls you upright. Let your body settle around your erect spine. Place your hands comfortably on your thighs without pulling your shoulders too far down or back. Tuck your chin and relax your jaw. Open your mouth slightly.

Gaze. Look downward about six feet in front of you with eyes half shut.

Breath. Breathe naturally through your mouth. One simple technique to keep the mind focused is the count the in-and-out cycles of breathing from one to 21. Every time thoughts come by, notice them and release them. If you get caught up in a train of thought, refocus on your posture and breathing and start again.

Adapted from information at www.shambhala.org.

Pamela Bond is a freelance journalist, trail runner and climber living in Eldorado Springs, Colorado.