The Forest Is Closed

The cost of admission may be going up

After driving nine hours to Taos, New Mexico, I was shocked to see a sign reading, “THE FOREST IS CLOSED,” …

After driving nine hours to Taos, New Mexico, I was shocked to see a sign reading, “THE FOREST IS CLOSED,” hanging over a band of pink tape blocking a trail. Thinking it was a joke or a temporary closure of a single trail, I kept driving up the Taos Ski Valley to run up Wheeler Peak, the highest point in New Mexico.

More pink tape blocked streamside pullouts, and I saw the dreaded “CLOSED” signs at other trailheads. At the Wheeler Peak trailhead, my worst fear was confirmed. “FOREST ACCESS PROHIBITED…National Forest CLOSED To All Use … No camping, no hiking, no biking, no horseback riding, no Jeeping, no ATVs, no motorcycles, no running … Extreme Fire Danger.”

Just then, it started to rain.

As I checked into a room for the night, I asked the clerk where I could go for a run. She suggested I could run on the road past the end of their fence for about a half-mile, or back down the road to the town for an almost three-mile loop. I just smiled. She said state parks and everything in the Carson National Forest, including the ski area, was off limits. A $5000 fine could be imposed on trespassers. She said government had run out of money fighting the fires in Los Alamos, and land was closed to all users. Then she offered to sell me a $5 ticket to go run a mountain on private property across the road. I smiled more.

I holed up in the room pondering my dilemma. Outside, rain poured down so hard the flammable forest vanished from view, so I turned on the TV. That’s when lightning cracked and blew out the power. So I sat in the dark with a flashlight listening to the monsoonal deluge and looking at maps of all the trails that were now illegal to run. They surrounded me.

In the morning I decided to pay the five bucks and hike Frazer Mountain on private property. I figured hiking would make it last longer than running, and it gave me time to think.

By the time I got to the summit and the coveted Wheeler Peak came into view, I was torn between going for it and toeing the line. On the one hand, only a few people in New Mexico that I knew of could keep up with me on a mountain trail, and I didn’t think any of them were forest rangers. On the other hand, I couldn’t outrun a radio. On the one hand, I saw no one out there but me. On the other hand, I was above timberline and easy to spot. On the one hand, the ground was still wet and I didn’t have matches or a lighter. On the other hand, I was leaving clear tracks.

Perhaps luckily, I forgot all about peak bagging when a herd of bighorns walked up the hill right past me, and stopped on the summit. It was nice, marvelous even, to sit on top of the peak with bighorns, soaking up the scenery (and wet ground) together. I called it good, and turned back.

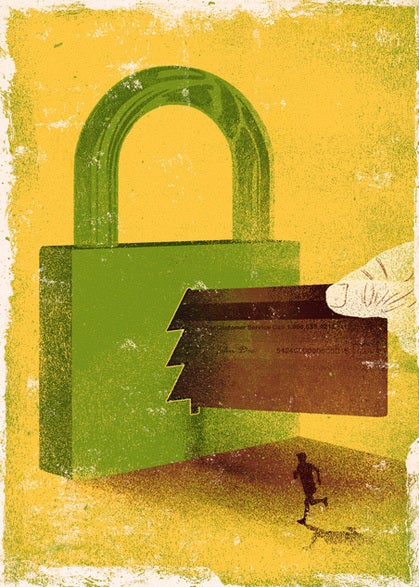

But, walking down the mountain, I envisioned a grim future. Our economy has been in the tank for a while and politicians are looking for new ways to earn revenue. If the government can close the forests and parks to everyone, they can just as easily open them back up and charge a user fee.

It’s already happening in pockets throughout the West. Fee collection at Maroon Bells near Aspen, Colorado, is being hailed as a “lifesaver” by local White River National Forest officials. You can drive through Utah’s Wasatch-Cache National Forest, but if you plan to park anywhere, you have to buy a permit. In Arizona, if you want to run the trail to The Wave, a geological wonder in the Vermilion Cliffs area, you have to buy a permit many months in advance, or take a chance in the daily lottery where only 10 people are selected for entry. I once watched a guy turn down a $100 bill for his permit.

As I strolled down the hill I recounted falling in love with trail running because it was free and easy.

Bernie gets his runs in while he can.