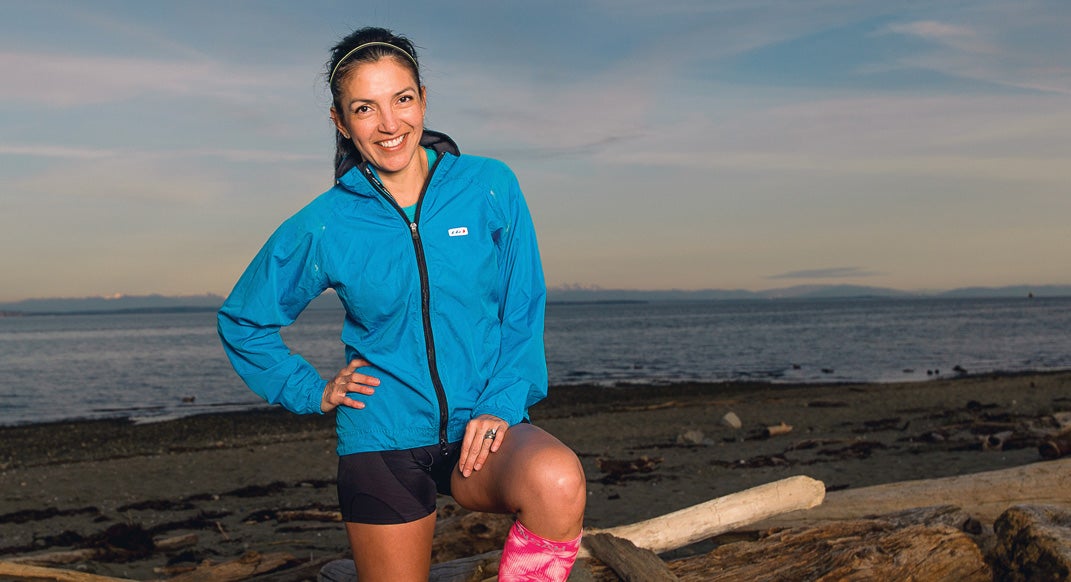

Taking Control

It was a dark wintry Canadian night in September, 2006 when Norma Bastidas quit running from her past.

Her 11-year-old son Karl, recently diagnosed with Cone-Rod Dystrophy (an incurable eye condition that leads to blindness), was curled up underneath her left arm and her other son nestled into her right shoulder. Both kids snoozed while Bastidas tried to blink away the tears. When she realized she could no longer temper the sadness, Bastidas did the next best thing. At 4 a.m., she went for a run.

“I didn’t want my kids to see me cry,” says Bastidas. “When I got tired, I sat on the curb and cried. And then I kept running.”

She didn’t worry about the fact that she wasn’t a runner. She didn’t even let the minus-20 Fahrenheit weather phase her, even though delicate snowflakes melted against her sweaty skin. Instead, Bastidas focused on putting one foot in front of the other. She ran until she conjured the courage to face her history. Then she ran some more.

Running From Her Life

Growing up in the slums of Culiacán, Mexico, Bastidas had never been a runner. Her father died when she was young, leaving her mother to single-handedly raise five children in poverty. Once El Chapo’s drug cartel took over her town, things got worse.

“If you have money, you can buy security,” Bastidas says. “But when you don’t have any, your life becomes a game of Russian Roulette.”

Then, an uncle that Bastidas trusted sexually abused her. With nowhere to go and no one to tell, she felt trapped. At the age of 17, she fled to Mexico City in the hopes of reinventing a new life for herself. For a while, it worked. She took classes to earn an aerobics instruction certification which she viewed as a solution to her financial concerns. But, on the day she received her certificate, she was kidnapped by two gang members. They spent one week raping and torturing Bastidas before inexplicably releasing her. “After that, I became terrified of everything,” Bastidas says. “I just wanted to live and I realized I needed to leave Mexico in order to do that.”

She began modelling, eventually securing a contract in Japan that paid roughly $1000 per month. Her mother was initially concerned about the distance, but reality took hold. Money talks, and the family needed the financial support. For Bastidas, it felt like a dream come true. Until it became her nightmare.

When she arrived in Japan, it became clear that Bastidas had unknowingly been trafficked into an escort ring. She didn’t speak Japanese and the club owners had taken her passport, so she was stuck.

“I had no recourse since I had signed the contracts,” Bastidas now says. “I don’t know if they did this to all the women but I think I was an easy target since they knew what type of background I came from.”

After nine months, she repaid her debt, and relocated to Calgary, Canada, to create a family.

Running for the Records

Bastidas spent her life running away from people and places. But on that chilly evening in September 2006, she made a decision: she could hide from the pain of her son’s eye condition, or she could face it head on, harnessing personal strength she never knew existed. She started running.

Just before her 40th birthday, a close friend encouraged her to run the Calgary Marathon. It was her first-ever race, and Bastidas qualified for Boston. Then, she registered for the grueling 78-mile Canadian Death Race, just three weeks after Calgary. During the run, she fell in a river and got hypothermia, effectively capping her race just shy of 60 miles. But, it didn’t matter: Bastidas was hooked.

“My body hadn’t belonged to me for so long and I finally found something I could control,” she remembers.

She kept running, but didn’t care much for organized events. Instead, Bastidas wanted to use her newfound talent to empower others. In 2009, she became the fastest woman to run seven ultramarathons in the world’s most unforgiving environments. She ran through scorching desert heat, thick jungle humidity and mind-numbing cold on seven continents in seven months, all to raise awareness for her son’s eye disease.

“When people are faced with adversity, they develop resilience,” says Ray Zahab, an endurance athlete and Bastidas’s former coach. “I see that in Norma. She is the most resilient person I know and that gives her unparalleled drive.”

Bastidas spent her life running away from people and places. But on that chilly evening in September 2006, she made a decision. She could hide from the pain of her son’s eye condition, or she could face it head on … She started running.

In 2014, she lined up an even bigger challenge: breaking the world record for the longest triathlon.

With the help of local Mexican shelters and the United Nations Blue Heart Campaign, Bastidas identified a popular human trafficking route from Cancun, Mexico to Washington DC. In total, her triathlon amounted to 95 miles of swimming, 2,932 miles on a bike, and 735 miles of running, which was double the previous record.

“Initially I pitched the idea in Mexico and all the organizations turned me down; they said they didn’t want to associate themselves with ‘those women’,” Bastidas remembers. “But in the middle of the triathlon, they posted videos of support and encouragement.”

She demolished the course, finishing in just 65 days. Two sex trafficking victims ran the last two miles with her.

Bastidas wants to shine a light on the trauma people experience on the USA-Mexico border. So she is currently training for her 2020 run of the 2000-mile USA-Mexico border, dubbed the “Other Side.” She is following a six-month training plan that calls for six days per week with a 2-4-6-8-10-12 hourly scheme. For the first month, she runs for two hours per training day; on the second month, she trains for four hours per day. She’ll continue this regimen until she completes a month of 12-hour training days—without any injuries.

“It all works together: her athleticism, her personal drive, and the fact that she has survived everything she has gone through and continued to grow,” Zahab says.

But Bastidas says she isn’t in it for her own glory.“Medals are great, but I do this for the visibility of my causes,” she says. “I can’t imagine a more important life role than being someone’s beacon of hope.”

Heather Balogh Rochfort is a Colorado-based freelance writer (follow her online @heatherrochfort).

If you or someone you know has experienced sexual assault, call the National Sexual Assault Hotline: (800) 656-4673