The Wisdom of Hippie Dan

And how I ran my first ultra, the 1994 Minnesota Voyageur 50-Miler

An excerpt from the forthcoming book by Scott Jurek with with Steve Friedman

Due to last-minute design changes, some of the text in the print version (June 2012, Issue 80) of this excerpt was repeated and deleted. We are very sorry, and offer this complete and correct online version.

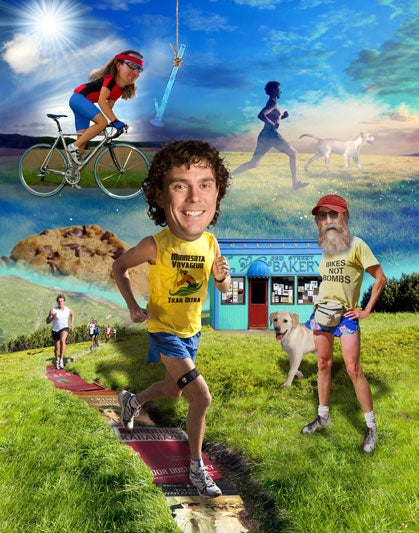

Illustration by Meg Bisharat

The more you know, the less you need.

—Yvon Chouinard

People are always asking me the same question. Why, when I could stay in shape with a 25-minute jog, do I train for 5 hours at a time? Why, when I could run a perfectly civilized marathon, would I choose to run four of them back-to-back? Why, instead of gliding over shaded tracks, would I take on Death Valley in the height of summer? Am I masochistic? Addicted to endorphins? Is there something deep down inside that I am running from? Or am I seeking something I never had?

At the beginning of college I ran because of Dusty. It was the summer after my freshman year. Dusty was living with guys in a place they called the House of Gravity. One of his roommates was a champion downhill skier, another was a world-class mountain biker. Dusty was bunking in the attic, where the temperature could drop to –20 degrees, and slept in a down winter sleeping bag from the army surplus store. They called it the House of Gravity because they smoked from a gigantic bong so often that much of the time they couldn’t get up. They decided the field of gravity was greater in that house than anywhere else. They even attached the bong to a rope so they could swing it from one person to another.

Meanwhile, I was staying with the Obrechts, the family that had re-formed the Proctor High School boys’ ski team. To see my mom and little brother and sister, I had to sneak back to the house when I knew my dad was working. Dusty and his housemates lived day-to-day. I couldn’t stop thinking about the future. I knew my skiing career was coming to an end; I didn’t have Dusty’s talent, and while I could hone my technique until a casual observer would think I was born in Norway, I also had figured out that guys like Dusty—and there were a lot of them at the upper levels of cross-country skiing—could almost always sprint faster than I could. No matter how hard I worked, I could never attain the pure speed that others could. I think whoever—or whatever—gave me determination and a good work ethic forgot to throw in fast twitch muscles. Then Dusty called and told me he had won a 50-mile race called the Minnesota Voyageur. He said he was going to run it next year, too, and asked whether I wanted to train with him. Of course I said yes. (I always said yes to Dusty.) I told myself it was to get in shape for the next ski season. But in reality Dusty was living the life I envied: free, fun, and fast. He was a dirtbag, and I wanted to be a dirtbag, too.

So we dirtbags trained. We would run for 2, 2½ hours, Dusty giving me shit the whole way. Jurker this and Jurker that, telling me I studied too hard, that I thought too much, I needed to loosen up, who cared if I was a fucking valedictorian. We picked up mud along the way and flung it at each other with various insults. Then one day, just when I was getting used to running distance, Dusty said we should mix up the training, and he threw bike riding into the equation. My experience riding was on the hunk of metal my dad had welded for me. Dusty promised it would be fun. He persuaded a friend of his to sell me his old bike—a Celeste green steel Bianchi. It was too small for me, so Dusty helped me put on an oversized mountain bike seat post. We’d go 70, 100 miles. Dusty knew how to ride, knew all the mechanics. He had raced against George Hincapie a few years earlier; Hincapie would eventually compete in the Tour de France. There I was, my giant seat post jabbing the seat into my nuts every time I hit a rock, ready to quit every 5 minutes. Except I didn’t. Maybe because it was such a relief to be away from studying and the sadness of my family, from watching my mom deteriorate and sensing my dad get sadder and more angry. I didn’t have the skills, and I didn’t have the bike, but I discovered something important during those rides with Dusty. I learned that even though I was a hack, even though I didn’t know anything about riding—I hadn’t read a single book on it, hadn’t studied a single essay on spinning or gear ratios—I could gut out those long rides. I wondered what else I could gut out.

I moved into the dorms my sophomore year. I signed up for a class with a Sister Mary Richard Boo, who was a notorious hardass, even among St. Scholastica’s hardass nuns. The first day of class she told us to get Crime and Punishment. We had five days to read it. It was a struggle between my other classes, my 30-hour-a-week Nordic-Track job, sneaking home to help my mom, and training for what I was sure would be my last season of cross-country skiing.

I looked at my classmates (the student body was 70 percent female), laughing on their way to class. I didn’t think many of them were on scholarship. They always seemed to have plenty of time. It seemed to me their life was school and intramural sports and parties. I felt out of place. It wasn’t the first time.

It didn’t help when Dusty would come over from the House of Gravity reeking of marijuana, hair down to his shoulders, making googly eyes at the coeds. He’d say, “Hey, maaaaaaaaaaaaaan,” and they’d blush. They all asked me, “Who’s your stoner friend?” Dusty was always a hit with the ladies. One day he slapped a sticker on my door that read: thank you for pot smoking. I left it up, and the visiting students would laugh as they passed by, but I’m sure their parents didn’t.

If someone had asked me at the time what I liked about Dusty, I probably would have shrugged. He was my friend, and that was enough. Now, though, I suspect it was because he embodied the worldview that was pulling at me. I had started delving into existential literature in high school and was continuing in college. Writers like Sartre and Camus described the plight of the outsider who felt like a stranger in an incomprehensible world. Hermann Hesse wrote about the search for the sacred amid chaos and suffering. The existentialists did not believe in living life from the neck up. They challenged me to reject artifice and the expectations of others, to create a meaningful life.

Back then, while my life never strayed from the conventional lines of socially approved behavior, the people I chose to hang out with created their own conventions—people like my uncle, my mom’s younger brother, nicknamed “the Communist,” who wore a Malcolm X cap, demonstrated to protect the rights of the homeless, slept on the beaches of Hawaii, worked on the Alaska pipeline, and usually had a copy of Mao’s Little Red Book in his pocket. And people like Dusty, of course, who now had a puke-green Chevy van emblazoned with a bumper sticker that read: hey, mister, don’t laugh, your daughter might be in here.

The most unconventional of all might have been the Minnesotan known as Hippie Dan, a modern Henry David Thoreau.

Dan Proctor was forty-five years old when I met him in 1992 at the co-op where he worked and which he co-owned, the Positively Third Street Bakery. He was 5-foot-10, all legs and long, gangly arms. He wore a T-shirt that said bikes not bombs, partly hidden by a beard that would have looked at home on a Hasid. He moved as if he was dancing at a Grateful Dead concert. His hair was plaited into two braids that hung over each shoulder. He talked fast—about the environment, and wheatgrass juice and whole grains, and living a mindful life. He spoke with a Scandinavian twang, and when he laughed, he sounded like a loon at dusk.

Hippie Dan made Thunder Cookies that were like chocolate chip cookies on steroids, with oatmeal and whole wheat flour and peanut butter and tons of butter. They were the best cookies I had ever tasted. (Rumor has it he once ran a secret bakery in the back of the shop, long since closed, and Dusty and his stoner pals used to sample those goods a lot.)

He was also a local running legend. People said that when he was younger, he would ride his bike to the local races. Then, wearing blue THE WISDOM OF HIPPIE DAN 49 jeans, he would leave all the people wearing shorts gasping as he shot ahead of them. Even Dusty seemed in awe of Hippie Dan. Dan had been running for twenty years. He didn’t have a car or a phone. Eventually he would get rid of his refrigerator. He talked about solar energy and living off the grid and minimizing impact—he produced one small garbage can of trash over an entire year. He also talked a lot about fossil fuels and the foolishness of humans. Essentially, he was trying to lessen his impact on the earth long before that became the trend. Some people called him the Unabaker.

Once Hippie Dan invited me to run with him. We followed his yellow labs, Zoot and Otis, and he told me to watch how effortlessly they ran. He encouraged me to notice how they seemed connected to their surroundings. Simplicity, he said, simplicity and a connection to the land made us happy and granted us freedom. As a bonus, it made us better runners. I didn’t know it, but it was a lesson I would learn years later in a hidden canyon in Mexico.

I longed for happiness and freedom as much as the next guy, probably even more, considering my schoolwork and jobs and the situation at home. I could see the wisdom in a simpler-is-better philosophy. But simple for me had never been, well, simple. I had al- ways tackled problems by study and focus. Consequently, when I began training with Dusty for his upcoming Voyageur, I suggested we read up on race strategy and training techniques. Maybe, I said, we should do some intervals or alternate sprints and jogs. Maybe we should count our strides. I think I mentioned heart rate monitors and lactate thresholds. Dusty told me I was full of shit. He said I thought too much. Do monster distances, he said, work your tail off , and that’s what will save your ass. He mimicked the Ricker’s voice as he beamed, “If you want to win, get out and train, and then train some more!”

So we spent that spring chugging monster distances that lasted 2, 3, 4 hours, runs all through and around Duluth. Dusty would come by and knock on my dorm door, and I’d take a break from The Brothers Karamazov, or War and Peace, or upper-level physics and anatomy and physiology, and we’d head out. We ran on paths that would narrow to trails and on trails that would narrow to almost nothing. We were running where deer bounded, where coyotes rambled. We ran through calf-deep snow and streams swollen with spring melt so cold that after a while I couldn’t feel my feet. Somewhere between my agonized, gasping high school forays to Adolph Store and now, running had turned into something other than training. It had turned into a kind of meditation, a place where I could let my mind—usually occupied with school, thoughts of the future, or concerns about my mom—float free. My body was doing by itself what I had always struggled to make it do. I wasn’t stuck on my dead-end street. No bully was spitting in my face. I felt as if I was flying. Dusty knew all the animal paths in the area, and after that spring, I knew them, too. We ran free all spring, sometimes talking, sometimes silent. We ran the way we always ran, Dusty in the lead, me behind. I knew my place, and it was fine. It was all quite fine.

I know a novelist who says he was never happier than when he was working on his first book, which turned out to be so bad that he never showed the manuscript to anyone. He said his joy came from the way time stopped and from all he learned about himself and his craft during those sessions. Running with Dusty that spring—not racing, running—I understood what the writer had been talking about.

I also thought I might do all right in a race. I entered Duluth’s Grandma’s Marathon in June, and all the training with Dusty paid off. I finished in 2:54. Not bad. I thought that, with focus and training, I could get faster.

Instead, with Dusty’s recommendation, I decided to go farther. I would enter my first ultra.

The day of the 1994 Voyageur we were both ready, and when Dusty—the defending champion—shot off the starting line, I shot off, too. Dusty didn’t call me Jurker or give me shit about my studies. We ran, and not just free. We ran hard. Minnesota in late July can be a muggy 90 degrees and muddy, and this day it was both of those, but we kept cranking. Then, at about mile 25, in a particularly gooey mud puddle, Dusty’s left shoe came off. He stopped to fetch it, and for a second I hesitated. How was I supposed to run without Dusty in front of me? He was the legend. I was the sidekick. He was the runner. I was just a stubborn Polack. I wasn’t sure what to do, so I did what I had been doing. I kept running. I ran for a few seconds, then a few minutes, and I looked back over my shoulder and didn’t see Dusty. I kept running.

Maybe my ski career was over. Maybe my dad would never be happy. Maybe my mom wasn’t going to get better, and maybe I’d always lead a dual life, split between diligence and the wild ways that Dusty represented. But at the moment I crossed the finish line, it didn’t matter. I had completed one of the hardest things I had ever attempted, and I told myself “never again.” I lay face down in the grass, panting, happy but feeling sick, totally drained. I didn’t have anything left. Was this what being a runner meant? Putting everything into a single race until you had nothing left to give? I had sensed a long time earlier that I had a talent for gaining speed when others gave ground, and I had wondered how that talent might ever serve me. In the rocky hills outside Duluth, bouncing on my cruel, nut-crunching green Bianchi, I had realized that no matter how much something hurt, I could gut it out. I wondered what that skill would ever be good for. I finished second in my first Voyageur, beating Dusty (who finished third) for the first time.

Hippie Dan had told me that we all had our own path, that the trick was to find it.

I think I had found mine.

EASIER, NOT HARDER

Coming from the flatlands, I had to learn to run uphill. Sharpening that skill, I improved all my running. You can, too, with or without hills. Next time you’re running, count the times your right foot strikes the ground in 20 seconds. Multiply by three and you’ll have your stride rate per minute. (One stride equals two steps, so your steps per minute will be twice your stride rate.)

Now comes the good part: Speed up until you’re running at 85 to 90 strides per minute. The most common mistake runners make is overstriding: taking slow, big steps, reaching far forward with the lead foot and landing on the heel. This means more time on the ground, which means the vulnerable heel hits the ground with more force on landing, creating more impact on the joints. Training at a stride rate of 85 to 90 is the quickest way to correct this problem. Short, light, quick steps will minimize impact force and keep you running longer, safer. It also will make you a more efficient runner. (Studies have shown that nearly all elite runners competing at distances between 3,000 meters and the marathon are running at 85 to 90-plus stride rates.)

I used to train runners with a metronome. Nowadays there are plenty of websites that list music by BPM (beats per minute)_—_try http://cycle.jog.fm/. Either 90 or 180 BPM songs will do the trick.

For Trail Runner’s book review, click here.