Trail Runner’s Guide to Carbohydrates

Unlike fat and protein, carbohydrate is not incorporated structurally into any body tissues. It is used only as fuel. Carbohydrate is stored in the liver and muscles as glycogen, but these stores are small—not even enough to fuel a marathon. This is why our carbohydrate needs are sensitive to our activity level. A desk worker who engages in no formal exercise needs very little carbohydrate and in fact shouldn’t consume much carbohydrate because any excess is converted to fat for long-term storage in adipose tissue. But a serious endurance athlete may need two or even three times as much carbohydrate as the average person.

Research going back to the 1960s has proven that the performance of trained athletes in racelike endurance tests is significantly affected by glycogen storage levels. When glycogen stores are maximized by a high-carbohydrate diet, endurance performance goes up. When glycogen stores are depleted by a low-carb diet, athletes bonk much sooner. The discovery of this causal link by Swedish scientists inspired the practice of pre-race carbo-loading (Rowell, Masoro, and Spencer 1965).

Most endurance athletes carbo-load before races. But they often overlook the importance of keeping muscles well stocked with glycogen throughout the training process, when glycogen stores are being drawn on heavily day after day. Numerous studies have demonstrated that athletes who eat more carbohydrates are able to maintain a higher performance capacity during periods of heavy training.

RELATED:4 Exercises to Tackle Runner’s Knee

Carbs And Training

One such study was performed by Asker Jeukendrup and his colleagues at the University of Birmingham, England, in 2004. A triathlete himself, Jeukendrup compared the effects of a high-carb diet (8.5 grams of carbohydrate per kilogram of body weight per day, or 65 percent of total calories) and a low-carb diet (5.4 grams of carbohydrate per kilogram per day, or 41 percent of total calories) on running performance during a period of intensified training. Seven high-level runners spent 11 days on each diet. Their training load was substantially increased for the last week of each 11-day period. At the beginning and again at the end of each heavy training period, the runners completed an 8-km time trial on the treadmill and a 16-km time trial outdoors. On both diets, the runners ran worse in the 8-km time trial after heavy training, but performance in the 16-km time trial worsened after heavy training only on the low-carb diet (Achten et al. 2004).

The more an athlete trains, the more carbohydrates that athlete needs in the diet to maintain performance. A good illustration of this principle is to be found in the diet of Greek ultrarunner Yiannis Kouros during a five-day, 600-mile race. To get through that event, Kouros had to eat and drink a tremendous number of calories—almost 12,000 per day—and nearly all of these calories—95.3 percent—came from carbohydrates. Kouros was wise to fuel his body in this seemingly unbalanced manner, as the body of a trained endurance athlete cannot store more than about 800 grams of carbohydrates (non-athletes store less than 400 grams) yet burns carbs at a rate of nearly 1 gram per minute even during moderate-intensity exercise such as ultrarunning. Thus, if Kouros had consumed “only” the 9.7 grams of carbohydrate per kilogram of body weight that Ethiopian runners who run “only” 110 miles per week consume, his glycogen stores would have been depleted long before he reached the finish line (even though the body can convert a certain amount of dietary fat into carbohydrate).

RELATED: The Science And Mystery of Ultra Fueling

Most endurance athletes exercise a lot more than sedentary folks whose exercise capacity is not affected by low-carb eating and a lot less than Yiannis Kouros during his running stage race. Therefore, the carbohydrate needs of most endurance athletes also fall somewhere between these extremes. Studies in which the carbohydrate intake of moderately trained athletes has been manipulated have generally shown that the average American diet—which supplies a moderate 3 to 4 grams of carbohydrates per kilogram of body weight—maintains glycogen stores well enough to prevent a drop in performance. For example, a study by William Sherman at Ohio State University showed that runners and cyclists performed just as well in exhaustive exercise tests after seven days on a moderate-carbohydrate diet as they did after seven days on a high-carbohydrate diet, despite the fact that the moderate carb diet reduced their muscle-glycogen stores by 30 to 36 percent compared to the high-carbohydrate diet (Sherman et al. 1993).

What lands athletes in trouble is switching to low-carbohydrate diets, such as the Zone Diet or the keto diet, that promise to increase endurance performance by boosting the fat-burning capacity of the muscle. Such diets do increase the muscles’ reliance on fat for energy during exercise, but they also reduce training capacity because the body always burns some carbs during exercise and when those carbs are not adequately replenished, performance plummets.

RELATED: Ask The Coach: Long Run Fatigue

Build Endurance

The Zone Diet recommends that carbohydrates account for 40 percent of total calories. The typical endurance athlete gets 50 to 55 percent of his or her daily calories from carbohydrates. In 2002 researchers at Kingston University in England studied the effects of switching to the Zone Diet on high-intensity running endurance in a group of young men. Before the switch, the men were able to run for 37 minutes and 41 seconds on average at 80 percent of VO2 max. After a week on the Zone Diet that time had dropped all the way down to 34:06—a 9.5 percent decline in high-intensity running endurance.

It is worth pointing out that reducing carbohydrate intake has never been shown in any study to increase training capacity. Nor has increasing carbohydrate intake ever been shown to reduce training capacity. Increasing carbohydrate does not always increase training capacity, but it does under heavy training loads. The natural conclusion to draw from these facts is that endurance athletes should take pains to ensure that they are consuming enough carbohydrates to meet the demands imposed by their training load.

RELATED: Understanding Glycogen, Your Body’s High-Performance Fuel

Most of us are familiar with carbohydrate intake guidelines in the form of recommendation percentages of total calories (such as the Zone Diet’s 40 percent guideline). These recommendations are not very useful because they make carbohydrate intake dependent on total calorie intake, which is only marginally relevant to actual carbohydrate needs. Carbohydrate needs are actually dependent on body weight and activity level. Therefore, they should be expressed as absolute amounts (grams) rather than as percentages of daily calories.

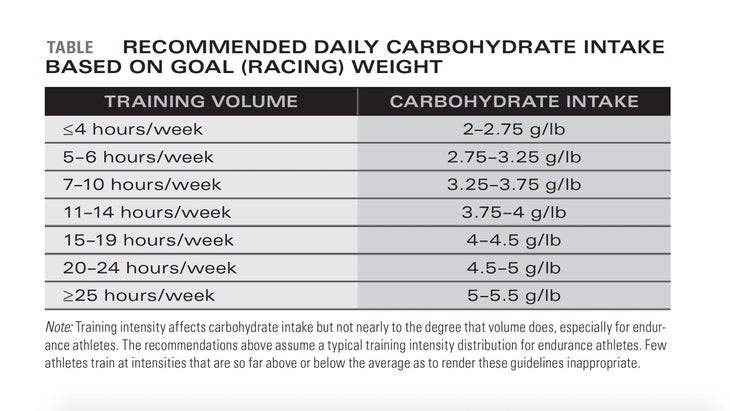

Based on my review of the scientific literature, I suggest that you aim for a daily carbohydrate intake target that is based on your training workload in the table below.

Many athletes with higher training loads are surprised by the large recommended carbohydrate intake values. That’s because the nutritional needs calculators that athletes may be familiar with do not account for how increasing training loads disproportionately increases carbohydrate needs versus fat and protein needs. Trust me, the numbers yielded by calculations based on the table above are valid. They are not absolute musts in all cases, however. If your carbohydrate intake is slightly lower than the amount recommended, and your training and recovery are going very well, you may not notice any improvement after increasing your carb intake to the recommended level. Then again, you might.

One obvious implication of these recommendations is that not only should some endurance athletes eat more carbohydrates than others, but also any single endurance athlete’s carbohydrate intake should vary as his or her training workload changes. If your training load increases, then your carbohydrate intake should rise, and if your training load drops, then your carbohydrate intake should also come down. The proportions of carbohydrates, fats, and proteins that non-athletes eat are as irrelevant to your body-weight management as an endurance athlete as they are to non-athletes’ efforts to lose weight and prevent weight gain. All that matters in this regard is the total number of calories that are consumed daily.

On the practical level of food selection, what does it take to meet your daily carbohydrate requirements? If your training load is moderate, it requires only that you include a few high-quality, high-carbohydrate foods in your daily nutrition regimen. If your training load is high, it may require such foods in every meal and snack throughout the day. Generally, the richest sources of carbohydrate are grains, dairy foods, legumes, and certain fruits (especially fruit juices).