New perk! Get after it with local recommendations just for you. Discover nearby events, routes out your door, and hidden gems when you sign up for the Local Running Drop.

Be yourself; Everyone else is already taken. —Oscar Wilde.

The cove on Ithaca Island in the Greek Ionian Sea looked idyllic and, equally as important, like a safe place to anchor. So I slowly motored into it on Adagio.

There was no sign of civilization apart from what looked to be an abandoned villa on the south arm of the cove, and the anchorage was empty. Which is to say not much has changed since the peripatetic Odysseus saw Ithaca upon finally reaching “home” in Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey over 2000 years ago. The rolling hills were covered with dense pine and lenga forests that dropped down to the crystalline water’s edge, which was fronted by a pebbly beach.

I needed to verify one more thing—access to a trail to run on the island. Opening Google Earth on my iPad, I located the cove and found a track that traced roughly along the water’s edge and ran well north and south of the anchorage. So, I dropped the anchor, secured it and settled in for the evening. As the water turned a cobalt blue, twilight and then darkness slowly accentuated my solitude in the isolated cove.

Awaking at 8 a.m. I brewed my daily cup of coffee and prepared for the day’s run. “Amphibious trail running,” for me, means going ashore to run either via Adagio’s inflatable dinghy of 70 pounds (ugh!) or, what’s easier and more refreshing, by swimming. Since the water temps in the Ionian Sea were comfortably in the upper 70s, I filled my waterproof bag with the essentials—shoes, socks, shorts, T-shirt, towel (the Mediterranean is notoriously salty) and a liter of fresh water.

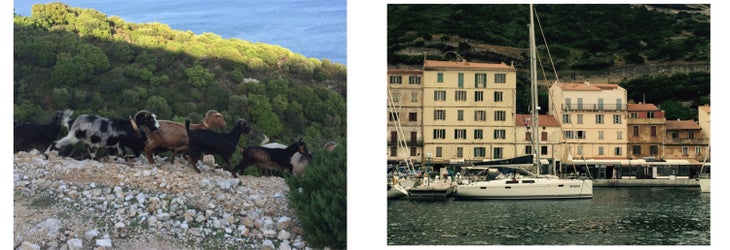

Dropping my boat’s transom, or the vertical section at the back, allowed me to slip into the water and swim with short fins while towing the floating waterproof bag with a rope around my neck to the beach 75 yards away. Once ashore, I toweled off, donned my running attire and arbitrarily decided to jog south on the dirt road. I came across olive groves, a herd of goats, an abandoned fishing boat and the ruins of a stone farmhouse during my six-mile out-and-back run over gently rolling hills. Swapping running shoes for fins, I swam back to Adagio and her warm freshwater shower in the cockpit.

During breakfast, I heard the low rumble of a powerboat offshore getting noticeably louder. Looking at it through my binoculars, I could see it was a grey boat heading straight toward Adagio at a very high speed. The only grey powerboats that travel that fast in the Med are the coast guard—presumably because they can afford the cost of fuel. Sure enough, it was the Greek Guardia Coasteria. As they roared into the anchorage, they did a sharp U-turn some 75 feet around Adagio, gave me a quick eyeball and then, without slowing down or as much as a wave or acknowledgement, hightailed it back out to sea, presumably reassured that there were no illegal migrants aboard.

The boat’s violent wake and the raucous noise of its engines had rudely disturbed my tranquil morning. Paradise, or the illusion thereof, is inevitably a temporal phenomena.

I checked the weather forecast, especially for wind speed and direction, and sailed south, in search of other anchorages but with no definitive plan in mind. A fixed itinerary is unrealistic given the weather and precludes being open to interesting places that pop up. “Vagabond sailing,” I call it. But in some comfort.

The Beginning: Getting Ashore To Run Trails

I began amphibious trail running some 25 years ago on California’s Channel Islands, which lie 18 to 30 miles offshore my hometown of Ventura, California. They are entirely protected by both the National Park Service and the Nature Conservancy. There are no dwellings saved for a few NPS campsites and the caretakers’ modest residences. Nor are there, from a sailor’s point of view, any moorings or docks to secure to.

You anchor, sometimes precipitously, 50 to 150 feet offshore. That plus the often rambunctious seas and winds of the Santa Barbara Channel keep “fair-weather” sailors close to the mainland harbors. High surf often required swimming to ashore. Dinghys or even kayaks could easily get upended.

What this means is that even in the summer you can find a cove and anchorage all to yourself. Running the islands’ over 100 miles trails is a throwback to when California was its native self. And gone, as in removed, are the herds of cattle, sheep, elk and even the feral wild pigs introduced by civilization in the past 150 years.

Why Do It?

The freedom of sailing one’s own boat allows a trail runner to literally get off the beaten track along any coast with suitable anchorages. In addition to southern California’s offshore islands, this quirky endeavor has included my spending a couple of winters in Mexico’s amazing Sea of Cortez and the Hawaiian Islands (windy with few secure anchorages), as well as summers in the Pacific Northwest and all the way up to Alaska. Amphibious trail running in the year-round frigid waters of the Northwest necessitates using my dingy or kayak to get ashore. Hypothermia is not an option. Nor is encountering an aggressive brown bear. My deterrent of choice? A small air horn which I fortunately have not had to test.

This “sport,” if I can call it that, is more akin to a lifestyle than a solitary pursuit. It calls for a deep love of sailing and trail running combined with a thirst for discovery. You must be able to deal with the vagaries of weather, a constantly changing and often challenging coastline and frequently sparsely inhabited interiors not even acknowledged in Trip Advisor. Thank God!

Club Med

And, now, what are the rewards in the amphibous trail running in the Mediterranean? For one, the “discovery” of unnamed, perhaps historically insignificant, but nevertheless fascinating ruins. For example, in Greece and Italy, running to the top of any good-sized mountain or hill will almost guarantee that you find a small, abandoned stone church of indeterminable age. This beats the crowded cathedrals and citadels of the big cities. Been there and done that.

I stumble into vistas I imagine have seldom, if ever, been seen by tourists. Running past small villages and farmhouses, I encounter rural inhabitants that are invariably courteous, friendly and helpful. Alas, few speak English but they communicate volumes through their smiles and gestures. In lieu of verbal directions, they have even taken me by the arm and steered me several hundred yards to a cafe or other point of interest.

And, certainly, there is always the risk of getting lost, of which I have a history. As a reconnaissance platoon leader in the army during the Vietnam war, I had plenty of opportunities to get “lost,” but always found my way back to my unit one way or another. I’m not above leaving small piles of stones, or self-made cairns, at forks in a trail or road to make returning to the anchorage less uncertain. Yet as some pundit said, “You only discover things when you are lost.” To include, of course, things about yourself. Being “lost” can indeed stir an awareness that fully activates the senses.

Lost and Alone: An Opportunity

The joy of solitude. I’m a true believer of the stoic philosophy that one’s circumstances in life have little to do with one’s happiness or sense of well-being. Solitude in an alien environment, provokes introspection and self-examination that can seldom be achieved in one’s comfortable home setting. Here, in the Mediterranean, my isolation helps to brings out a deep appreciation of the long, tumultuous and multi-layered history of the area, and my own relative insignificance.

Lest I give the impression that I’m a total misanthrope or sailing hermit, one of the most profound advantages of solo sailing and running versus sailing and running with friends is that I’m more likely to engage with strangers. That could be other boaters in a marina or anchorage, simply folks sitting next to me in a restaurant or locals I meet casually in the market. In Trieste, Italy, I once had a lengthy conversation with an Austrian in a restaurant.

Saying goodbye, he added, “So you travel around the world and meet people like myself and we become friends and then you never see them again?”

“Yes,” I replied, “something like that.”

He looked at me querulously and then shook his head in total incomprehension.

My mantra: be curious and adapt. In the most desolate of places there is always something to experience if you leave yourself open to possibility.

Possibility Amidst Uncertainty

I was warned that getting into Croatia would be a bureaucratic nightmare. As I walked into the immigration office at the harbor of Cavtat, I was greeted by a pleasant middle-aged woman who would handle my paperwork. While making small talk, she mentioned an unusual hobby. You guessed it—trail running. My entry was significantly expedited, and even led to a guided run along a Big-Sur-like coast.

But, usually, you’re constantly dealing with an uncertain environment, which can be frustrating and times consuming. Like taking a whole day to find a laundromat, learn its nuances, and then actually do your laundry. Or even trying to find a decent meal in a strange village. But, as I often have to remind myself, this all part of the adventure, even if it’s just the spin cycle.

There is also the uncertainty of a trail run on unmarked trails that may lead to the town dump, a pack of barking dogs or even a cemetery. But cemeteries in the Med can be fascinating and, even, useful.

Midway through an early morning hot and humid run in Turkey, I had already emptied my water bottle with miles to go. There was a modest, small cemetery along the trail. At the head of one of the graves was a gallon plastic jug with about a quart of, hopefully, potable water still in it. The flowers the jug had served to water were as dead their grave’s occupant. After a moments hesitation, I determined my hydration needs were the greatest. It was a very brief moral dilemma.

Uncertainty keeps you present in the moment. This can be both liberating and unnerving. Unnerving in the moment and liberating once you’ve experienced it. Similar to passing through a stormy gale at sea.

I rented a car in Albania to explore the country’s interior. The flat coastline offered few attractive anchorages or running routes. One of my destinations was the so-called “Albanian Alps,” a bit of a stretch compared to the “real” Alps but nonetheless scenic with runnable foothills. I parked the car next to a trailhead whose attraction was that it led toward some snowcapped peaks in the distance.

The trail was deserted and bordered by dense, reedlike vegetation. Then I spotted a man. He was an older fellow wielding a long machete with which he was harvesting the reeds for God knows what purpose. Near him was a rusty motorcycle with a basket on it half full of this prolific and somehow valuable weed. He looked at me grimly with an expression close to hostility. I waved but his steely expression didn’t change.

Over the next mile the weather deteriorated to a light drizzle as the skies darkened ominously. I turned to run back, hoping to beat the storm. I was then overcome by dread. What if this fellow was waiting to ambush me on the way back? No one would ever know or hear my cries for help. I sped up as I neared his location and picked up a baseball sized rock. Running past him he barely looked, and I reciprocated, avoiding eye contact. Whew, I might have dodged that bullet, or rather, machete.

Creative Adaptation—With a Purpose

On my sailing-trail-running adventures I create my own, simple rituals. As in, I will run every other day. On alternate days I spend one hour on my portable rowing machine. Daily meditation. A daily journal entry. I’ll spend a bit of time each day reading the stoic philosophers. Audio books and podcasts on a bluetooth speaker in the cockpit are the perfect companion for a solo sailor on a long day. I try to pick those that relate to the history of the geography I’m in. Homer’s Odyssey, of course, in Greece. And Dumas’ The Count of Montecristo in France and Corsica.

On a sailboat it’s easy to drift mentally and physically into lethargy. I need some direction and purpose, yet with flexibility, that is adapted to my circumstances. You need to create your own “balance,” as you go.

Marinas with their towns and cities and fellow sailors dockside can offer a welcome respite from the solitude of anchoring. Some coastlines offer no alternative. There are no protected anchorages. There’s usually some interesting history if only the ever-present harbor citadel, or a good restaurant and plug-in electricity dockside.

They’re also an opportunity to do some cross training. I’ll often Google local gyms, some of which can be comparable to modern U.S. gyms but some, I’ve experienced, are reminiscent of those from the 1950s or ‘60s, kind of like “Rocky’s gym” complete with the memorable odor of stale sweat. In those cases, I’ll call the swankiest hotel in town and inquire about its day rate. Usually for 10 to 15 euros you’ll have the run of their facility to include gym, luxury spa, sauna and perhaps an indulgent massage.

The biggest issue in solo sailing in the Med might be loneliness. I’ll go days without a conversation in English. I tell myself this builds self reliance and fortitude but it’s always good to see a boat with a north European flag on it—they will speak English.

I have only encountered one other solo sailor in 15 months during four seasons in the Med. He was a 70-year-old weather-beaten Australian I met in a Tunisian marina in 2016, with a 40-foot sailboat that had a busted transmission and tattered mainsail. Like most Aussies, “John” was typically phlegmatic about his predicament as he drank his beer. “Yeah, I don’t know how long I’ll be here but it’s all OK. No worries, eh, mate?” he said. I admired his stoic indifference.

Other sailors tell me they have run into one or two solo sailors. They consistently describe them as, “Yes, he was a crazy Brit,” or “crazy Swede”. Having met only a half-dozen crewed American boats during my time in the Med, I have no doubt I’ve earned the moniker of, “Yes, he was that utterly crazy American sailor—who also ran.”

Jim Eisenhart is an avid trail runner, sailor and skier. He has completed over 35 marathons and ultras. His last marathon, the Catalina Island Marathon, he completed at age 70 in 2018. When not living the life of a vagabond sailer and trail runner he lives in Ventura, California.