Running China's Tiger Leaping Gorge

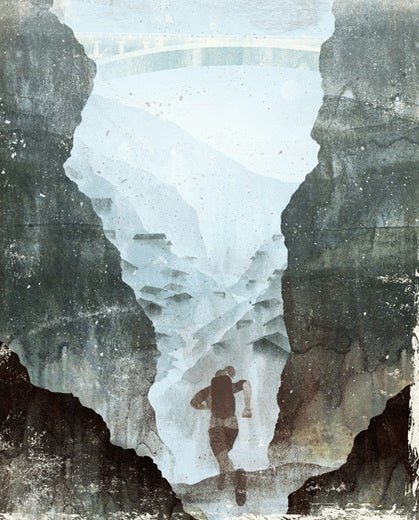

A runner discovers the adaptability of human nature on a run through one of the world’s deepest gorges.

China’s Tiger Leaping Gorge is a dramatic slice of rock and river in the country’s southwestern Yunnan province. At 10 miles long …

Illustration by Kevin Howdeshell

China’s Tiger Leaping Gorge is a dramatic slice of rock and river in the country’s southwestern Yunnan province. At 10 miles long and 13,000 feet deep, it’s one of the deepest gorges in the world, and possibly the most scenic natural wonder in China. Jagged 15000-foot peaks line the river, with vertical walls plunging to the water. Terraced fields layer the few gently-sloped hillsides on the northern side of the valley, where small villages make a thin chain across.

In November 2010, I was in Yunnan touring the province’s ancient Tea Horse Road, an old trading route similar to the Silk Road. Inspired by the tales of historic, arduous journeys, my friend—a British expat living in Yunnan’s capital Kunming—and I made plans to run the gorge. Matthew, a programmer, is drawn to the logistics of run: how far, how long, what elevation, what kind of fuel? I am pulled by the intense scenery and the physical challenge, and so together we balance inspiration and logic.

Two “paths” run the length of the gorge. The “low path” is actually a road under constant construction thanks to frequent landslides. It is mostly paved, and not good for walking or running due to vehicle traffic emitting heavy fumes. The singletrack “high path,” however, is an old transit route for a minority tribe called the Naxi, who populate the small hamlets that cling to the gorge’s hillsides. The high path climbs, drops and snakes along cliffs between villages and at the foot of magnificent mountains, and is still used every day by the Naxi.

The trek from one end of the gorge to the other is considered extremely difficult, and most trekkers take two or three days to walk it. Though I am drawn to adventure and never met a hiking trail I didn’t want to run, I am nervous about the gorge.

For one thing, I don’t have access to familiar food, let alone energy gels or sports drinks. Can I handle a 14-mile trail with 4000 feet of elevation gain? And will I be able to stay hydrated at altitudes of 6000 to 10,000 feet? I cannot imagine drinking any unfiltered water in a country as polluted as China, nor, at this point, do I know if any is available on the trail anyway.

The first thing we sort out is breakfast. Matthew and I wake before dawn, and he orders us gan bian tu dou si, a plate-sized hash brown topped with a fried egg. Carbs and protein—check. I swallow a few thick mouthfuls of instant coffee (caffeine—check), and we begin our ascent, catching the high trail where it intersects with the low road across from our guesthouse.

We climb the dry trail at a slow jog for at least an hour before the sun crests the opposite peaks, light beaming through gaps in a long row of sharp saw teeth covered in snow. Clouds still cover the river and canyon below like a fluffy mummy bag, though they rise and dissipate as the day warms. As we round a corner, a Naxi goat herder—a small man dressed in a yellow sweater, collared shirt, trousers and a signature blue Naxi cap similar to a golfer’s billed hat—and his herd of goats, squeezes by. He smiles and shouts, “Hello!” We step aside, letting the goats clang by.

After about three miles of ascent, the trail flattens out and contours along the vertical rock face. Waterfalls tumble down from the snowy mountains above, safe to drink from and sweet and fresh. We step carefully across their paths. Evidence of human life is everywhere. From the views of the road construction below to the occasional small piles of garbage, I’m reminded that despite the magnificent natural drama of the gorge, this is a place where people live.

We begin a grueling climb to the highest point on the trail, roughly 10,000 feet, and our run slows to a hike. At the top of our climb, an entrepreneurial woman appears on the trail with a basket of bottled water and bananas on her back. I eat a banana and feel revived, while Matthew demolishes a small bottle of water in three swallows. The sun glitters on the river below from a bright, blue sky, and snow from the line of vertical, triangle is swept off the summits in a high-alpine wind.

Then we descend the “28 Bends,” a series of knee-battering switchbacks that drop about 2000 feet. The trail mellows and we pass through more villages, clusters of small wood houses huddled against green hillsides, and we can look down from the trail into courtyards. A small shop sells more food and water geared toward trekkers. I stop to use a rural toilet in a village next to the trail: three patchy wood walls surrounding a slick tile floor with a sloped ditch in it, emptying onto the ground below.

The last couple of miles of “trail” is, in fitting with China’s rapid development, on a newly paved road. The cement leads downward, and sections of dirt trail are visible as shortcuts between the road’s switchbacks. The hot sun and hard pavement begin to work against us, and we walk the half mile or so to the trailhead in Qiaotou, a busy town with a highway linking the larger cities of Lijiang and Shangri-la.

We replenish with a random assortment of food: a Spam omelet, fried rice, fresh fruit. It took us 4.5 hours to cover the difficult 14 miles. As I reflect on my run, I’m in awe of the adaptable nature of humans. Though farming and herding are still a part of their lives, the guesthouses, small cafes and shops, and even the woman who hiked up the trail with sundries are her back are all testaments to ability of humans to change with and adjust to new circumstances.

And as for me? I think my recovery meal will definitely involve Chinese food.