The Twilight Zone

You’re running through another dimension–a dimension not only of sight and sound but of mind. A journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination.

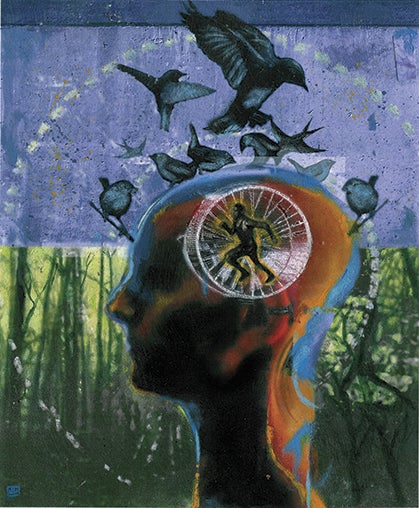

Illustration by Jeremy Collins

Andrew Thompson was on his way to becoming only the seventh runner to complete the Barkley 100-miler in its two-decade history. “I had 20 miles to go and plenty of time,” recalls Thompson. “I was running well and feeling very good.”

What was not to feel good about? A Barkley finish is a life-defining achievement for even the most elite runner. The Barkley staggers through the rugged Tennessee wilderness, and features over 60,000 feet of climbing—twice that of Colorado’s heinous Hardrock 100. Bushwhacking is frequent, brambles slice flesh, river crossings are dangerous and staying on course demands expert navigational skills.

But Thompson, 28 at the time of the race, knew he had the gusto to finish. He’s a blood-and-guts runner, trained on the craggy trails of his home state of New Hampshire, and has run some of the toughest trail races in the country. In the summer of 2005, he set the speed record for the Appalachian Trail, covering the 2,174 miles in 47 days and some change. Thompson had total confidence in his body.

What Thompson didn’t count on was his mind turning adversary.

“I’d been running for 49 hours without sleep, when things became hazy,” he recalls. “Switchbacks became confusing. I felt I was just walking back and forth on a single stretch of trail without going anywhere. Soon, I couldn’t even tell whether I was ascending or descending a mountain, or just standing still. Houses started popping up along the trail in the brush. Then office buildings.”

Thompson knew of the Barkley’s reputation for generating outlandish hallucinations, and his mental disposition went from bad to worse. “Suddenly, an entire neighborhood of homes appeared. I had vivid images of people walking by, cars driving past. I was even able to identify the specific models of the cars. Then, things got weirder. I suddenly became a garbage man trying to identify which houses to visit for trash duty, and which to bypass. Then, I changed jobs—I was a landscaper, carrying lawn refuse from the house to a street. Next, I was an ice deliveryman. Does this house need ice, or are they all set?”

In his delirium, Thompson wandered off course, perhaps to deliver imaginary ice, and joined the ranks of other Barkley DNFers.

“I lost my mind in the full definition of the phrase,” he explains. “I worked so hard to get to that point, and then I pissed away the Barkley. I hate hallucinations!”

WHY ME?

Thompson’s experience is not uncommon for runners who participate in extreme endurance events. Textbooks define hallucinations as sensory perceptions not related to outside events. They’re simply seeing or hearing things that aren’t there—your mind turning cartwheels, pulling a sleight-of-hand on your sense of logic and reality.

Hallucinations are typically associated with drug use, psychosis or neurological illness. So what causes them in long-distance running events? Dr. Jeffrey Lynn, an exercise physiologist from Slippery Rock University in Pennsylvania, studies running hallucinations as part of an ongoing study on the physiology of running 100-mile races. “Based on my experience, hallucinations in endurance running events are typically caused by the combination of sleep deprivation and exhaustion,” explains Lynn. “I think both factors are responsible.”

Lynn acknowledges that little is known about the relationship between endurance events and hallucinations, or their inherent dangers, but sees no reason to panic. “Right now I don’t know of anyone studying what’s happening when runners hallucinate,” he explains. “However, I doubt that hallucinations pose much of a danger. They’re usually innocuous and runners typically pull out of them quickly.”

ILLUSIONS OF GRANDEUR

Most trail runners experience hallucinations of the garden-variety type: rocks becoming raccoons, boulders turning into cars, grass clumps morphing into giant spiders. Some, however, transcend the common.

Take, for instance, those of Marshall Ulrich, 54, a world-class trail runner, adventure racer and mountain climber from Colorado. Ulrich’s exploits are legendary. Thirteen times he has finished the Badwater Ultramarathon, a 135-mile summertime sweatfest across Death Valley and up Mount Whitney, winning four of those races. He’s run a 586-mile quad Badwater, repeating the course four times consecutively. In 1989, he became the first runner to complete the Last Great Race, finishing all six major 100-mile trail races in one summer. He’s also stood on the highest peak of every continent, and is one of only three athletes to have competed in all nine Eco-Challenges.

Ulrich also hallucinates in epic fashion.

During his 1999 self-supported solo crossing of the Badwater course, where he pulled 225 pounds of water and food in a rickshaw for the entire 135 miles, Ulrich’s mind played wonderful tricks. “It was the second day of my crossing, getting toward dusk,” explains Ulrich. “I was running at about three miles per hour, when suddenly, a woman in a silver bikini appeared. She was rollerblading at a pretty decent rate. Every so often, she would turn around to smile and wave at me. She was just perfectly proportioned, this ideal woman in the middle of Death Valley.

“I’ve had hallucinations before, so I knew it wasn’t real,” adds Ulrich. “But this was such a good one, and so entertaining, that I perpetuated it for six or seven minutes. This is one I didn’t want to go away.”

At another point in his lonely solo crossing, Ulrich subconsciously created his own crowd boost. “I was pulling the cart along the left-hand side of the road,” he recalls. “And a massive, wingless 747 pulled up beside me. I looked up and through the portals saw people waving. Men, women and children were all cheering me on.”

Envisioning airliners, however, did not play as well with Ulrich. “Seeing the skater was entertaining, but not the plane,” he remarks. “That vision was just bizarre, a little too vivid, too real.”

NOT FOR HARDCORES ONLY

Hallucinations are not the sole domain of hardened veteran runners. The vulnerable minds of novices are equally susceptible. In 2004, Baltimore runner Justina Starobin, 44, was cutting her 100-mile teeth in Vermont, when she encountered a cinematic oasis in the New England woodlands.

“It was two in the morning, about 72 miles into the run, and I was practically sleepwalking,” says Starobin, “when on a hill in front of me, I saw a drive-in theater, with a love scene playing. It involved a woman with dark, shoulder-length wavy hair and a clean-cut, dark-haired man. Both were very tan, caressing each other and talking.”

Starobin’s pacer sought to be a voice of reason, and argued that there couldn’t possibly be a drive-in theater there, but Starobin wasn’t buying. “I was certain [my pacer] was wrong,” she explains. “I could see the movie right in front of me, so I didn’t say anything. I was just focusing on the dialog and story.”

As the tandem neared the top of the hill, reality abruptly ended the movie. What spurred Starobin’s hallucination was an aid-station light casting shadows of swaying trees on the side of a barn. “I was very disappointed,” offers Starobin.

Mind alterations helped motivate Wyoming runner Kevin O’Neall, 49, to his first 100-mile finish. It happened at the 2003 Javelina Jundred, an autumn amble through the stark beauty of the Arizona desert.

“The night had a dream-like quality,” remembers O’Neall. “I recall feeling calm and safe in the night air with the full moon and coyotes howling. Then an eclipse began, and the sudden lack of light was eerie. The raucous coyotes quit singing. Right in front of me, I saw a man hanging by a rope. He was wearing a cowboy hat and boot-length duster. There were no trees nearby for him to be hanging from.” The man turned out to be a bush, and the hanging rope a tall reed protruding from behind. The shock of the vision gave O’Neall a second wind.

Later in the race, large Saguaro cacti began chasing O’Neall, prodding him to a sub-30-hour finish.

FAMOUS COMPANY

Often, public figures or characters weave their way into the mental fantasies of trail runners. Lisa Demoney may or may not have seen late Grateful Dead singer and guitarist Jerry Garcia wink at her in the later stages of the Massanutten Mountain 100-Mile Run. Scott Brockmeier happened upon Saddam Hussein during a 70-mile run across the Smokey Mountains, in Tennessee.

During an Eco-Challenge, Marshall Ulrich watched a teammate’s face metamorphose into that of gap-toothed MAD magazine icon, Alfred E. Neuman. On his Appalachian Trail quest, Andrew Thompson saw singer Dave Matthews’ face perfectly etched into a tree, and later Michael Jackson’s face in another tree—a vision that he found quite disturbing.

Florida runner Jeff Bryan encountered a former president during a recent Pennar 40-Mile Endurance Run, an out-and-back jaunt from Pensacola Beach to Navarre Beach. “I crashed and burned,” he says. “I was suffering from major dehydration and cramping. Between miles 30 and 35 I was running with a friend, Gary Griffin, when Bill Clinton rode by on a bicycle. He waved, shouted some encouraging words and rode off into the horizon.”

“I looked at Gary, and Gary looked at me,” Bryan continues. We continued for about half a mile, when I couldn’t contain my thoughts any longer, and asked, ‘That was Bill Clinton who just passed us, wasn’t it?’ Gary got a shit-eating grin on his face and responded, ‘Pal, I’m glad you saw him, too.’”

“As a Republican, I found it very scary,” adds Bryan.

CAN YOU HEAR ME NOW?

Hallucinations are generally thought of as being visual, but often manifest themselves in other ways. Blake Wood is a tough-as-steel trail runner from New Mexico who has seen Volkswagen Beetles hanging from trees and rock lichen transform into a running friend. Once, in the later stages of Barkley, he chased a non-existent kitten through dense woodland, believing it belonged to a park ranger. But on one occasion, Wood’s ears deceived him.

“It was the 1997 Barkley and I was approaching the Coal Pond area, just beyond Son-of-a-Bitch Ditch,” explains Wood. “I heard someone blowing a whistle in the dark. I could only assume they were in distress, so I called back. ‘Who are you? Are you in trouble?’”

“When I received no answer, I got really concerned and ran toward the sound, the whole time yelling ‘Hold on! I’m coming! It’ll be OK!’ I ran and ran and ended up on the shore of Coal Pond. The whistling was just frogs peeping.”

Hallucinations don’t require the victim to be on the move. The overactive mind may even lead to post-race visions.

Jeff Keyser, 44, of Alabama, completed the 2003 Mountain Mist 50K Trail Run near Huntsville, Alabama, as his fourth marathon or ultramarathon in 10 weeks. “I ran a fever, and was cold and miserable the entire race,” says Keyser. “Afterward, the only thing I could think of was getting to my car and into clean clothes. I was shaking uncontrollably. As I approached my car, I noticed a cowboy kneeling next to it, panning for gold. He had a big hat down over his face and one of those long coats.”

Further inspection revealed the culprit as a three-foot shrub. “I do not have any fond memories of that day,” says Keyser.

Veteran Massachusetts runner Stanley Tiska, 48, had a similar experience. It happened following a vigorous 35-mile training run on the Metacomet-Monadnock Trail, which threads through the scenic Berkshire Mountains. Tiska wandered off course and ran longer and harder than planned. “After the run I was driving home alone, very exhausted,” he recalls, “and noticed a speed skater racing me. I could see the texture of his black body suit and hood, and his muscles straining for more speed. All I could think about was ‘Wow, look how fast he’s going! He’s doing great!’”

Tiska can usually erase his hallucinations by diverting his focus to other objects, but the speed skater proved persistent. Tiska was forced to pull over for a rest break. “Not only did I have an unforgettable run that day,” he says. “But also an unforgettable drive home.”

This article originally appeared in our January 2006 issue.

Michael Strzelecki, of Catonsville, Maryland, is no stranger to running hallucinations. Once, during the late stages of a 24-hour run, he yanked his wife (pacer) out of the path of an imaginary car trying to run them over.