Dropping Out

Revisiting the walk of shame

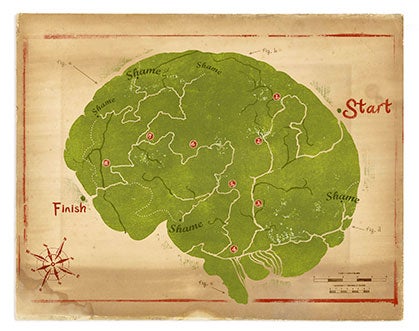

Illustration by Jeremy Collins.

Twenty miles into the 50-mile race, two women passed me chatting about Christmas presents and holiday cards. The rain had been falling since before the 5 a.m. start, it was a few degrees above freezing, and I had been walking through the mud for too many hours. For the short while that I was able to accelerate and keep up with the two, I deduced that they were mothers of teenage boys. Ben was going to Cal Poly, and Mike was the starting forward for the high-school lacrosse team. Meanwhile, I was embroiled in an existential crisis, asking myself whether we runners are morally obliged to finish a race.

If there’s one place where runners can easily spend too much time, it is within the confines of our own brains. If things start to sour at mile 20 of a 50-mile race, you’re going to spend a long time in that cell.

The questions from the start of my decline had been pointed and direct: are you hungry? Thirsty? Were you well-rested?

As I slowed, the questions became much more vague and philosophical: Why do you suffer like this? What do you learn? What are you proving?

Finally, after walking several miles through the cold rain and mud, I asked myself the question that brought on my little crisis: are you going to quit? One of the few defining characteristics of this sport is that you don’t just quit. You run. The moment you stop running, you are no longer participating—by definition, you stop being a runner. Before I drop in any run, I tell myself that the ability to run is a gift, that I owe a finish to those who can’t run.

When you toe any starting line, it is understood that you will suffer and your ego will be tested. In a sport so cut and dried, so black and white in terms of times and places, the ego is eventually called in for questioning.

Perhaps the suffering is why not all runners choose to race. Or they know they might get too revealing a look at that ego we so often try to conceal. The stakes go up when a runner pins a number to his or her shirt, and there’s more to gain and more to lose. It is the difference between singing in the shower and singing on stage.

Most of us go into a race with goals. Over years of racing, we refine them. With intentions of a fast race and a respectable time, I had apparently refined my goals so pointedly that I hadn’t factored in finishing the race. That was a given. Or so I thought.

I’ve suffered this crisis before, usually at a point where I’m wishing for an honorable retirement from a race in the form of a broken ankle and a helicopter ride down the mountain. When it became obvious that I was not moving fast enough to break my ankle, I removed my bib and checked out at the next aid station.

You might think that dropping is going to relieve you from your pain and anguish, but really it just becomes a trade. Pain for shame. On that cold, muddy day, I bowed my head and made my way to the car.

“The walk of shame” used to mean something entirely different to me. A notion that was once accompanied by guarded snickers now elicits the question, “Are you hurt?”

I hedge. “Well, kinda.”

Curious of the race outcome, I drove to the finish line, though it certainly wouldn’t make me feel any better about my own decision.

Runners were death-marching across the line. One man was crying, saying, “I didn’t think I could do it.”

I hurried past him.

Several beers later, I found Hal Koerner, hobbling around after finishing. With an old account of his 38-hour epic at the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc two years ago still swimming around in my head, I asked why he had powered through to that finish in France. It had required an unanticipated 15 extra hours of exhaustion and “chafing in all the wrong places” that would have crippled a normal human.

“I had dropped out of that race once before is why.”

I walked away consoled.

Running is a journey of highs, lows, DNFs and DFLs (that’s Dead F’ing Last, if you wondered). Quitting is sometimes a first step toward finishing.

Rickey Gates prefers the original Walk of Shame.