An Advanced 50-Mile Ultramarathon Training Plan

Two athletes trail running in the hills during sunset. Shallow D.O.F. and with motion blur.

A while back, badass athlete Andy Boyle reached out to say he had used the Trail Runner 100-mile intermediate/advanced plan to win the Kodiak 100K. I was partly horrified. One stray typo and instead of doing 4 x 20 sec fast, Andy could have been doing 4 x 20 sex fast. Overtraining is not sexy.

I was also so happy. The goal with these articles is to lovingly throw as much information at the wall as possible, and see what might possibly stick for a few athletes. And one of the training plans that is missing from the archives is for 50 miles. That changes today!

50 miles is an ultra-sweet spot, rewarding a well-rounded athlete combining a skill-set that can feed into long-term growth at shorter and longer distances too. There are four main elements to think about.

RELATED: See our full library of training plans here.

Velocity and climbing output at lactate threshold

If I could only see one piece of data to predict an athlete’s future, it would be their credit card number. Just trust me. But the second piece of data would be their vamLT. Initially a cycling term, “vam” stands for “velocità ascensionale media” or “average climbing speed.” LT is approximately 1-hour effort, with variance based on the athlete. So vamLT is average climbing speed that an athlete could sustain for around 1 hour.

My wife/co-coach Megan and I like vamLT because it has overlap with vLT, or velocity at lactate threshold, a common term used for road running (we talk about it on our podcast here). Because uphills have different biomechanical patterns, yet running economy on uphill grades correlates with level and downhill grades, vamLT is a good catch-all variable combining muscular endurance and aerobic capacity.

At the upper end of the output spectrum, VO2 max is highly genetic and not very trainable after an initial growth period. Meanwhile, LT can progress longer-term, and it has more predictive value for longer events like half marathons, marathons, and ultras. Improving vLT and vamLT requires an endurance base, well-developed output at VO2 max, and specific tempos and cruise intervals. Show me an athlete with a high vamLT, and I’ll show you an athlete that is no more than 6 weeks away from a strong performance at any event, from a 5k trail race to a 100 mile mountain ultra.

Takeaway: The first 6 weeks of the training plan are focused on building upper-end output with speed and hills, then emphasizing tempo workouts.

Velocity and both climbing and descending output at aerobic threshold

While vamLT is a flashy pony, the workhorse of the aerobic system is output around aerobic threshold. AeT is the intensity range when the body switches from primarily lipid metabolism to glycogen, with breath rate picking up and efforts getting less sustainable over a few hours. Most athletes can train to race ultras at a relatively high percentage of AeT, so if they raise that AeT ceiling, it makes breakthroughs possible where athletes actually RACE at the ultra distance. That’s where the amorphous science of fatigue resistance comes in.

An interesting wrinkle for the training nerds out there: elite road marathon training has a heavy emphasis on compressing LT and AeT, so that athletes can race at relatively high efforts for up to a few hours. That’s a great jumping-off-point for 50 mile training, but if an athlete stops there, it’s likely that they’ll bonk unless they go out relatively easily, since the burn rate will be too high at 3+ hours. So 50-mile training involves a heavier emphasis on lower-intensity long runs close to race day.

We’re going to need botox because there’s another wrinkle. If athletes train to race at a high percentage of AeT, they’ll be running downhill pretty darn fast. That focused and purposeful downhill running can be difficult at first, and purposeful downhill running needs to be an emphasis on some long runs to avoid jello legs on race day.

Takeaway: Easy/moderate long runs and steady efforts over race-like terrain are a key part of the training plan throughout, but especially in the final 6 weeks.

Aerobic endurance

A 50-miler will take anywhere from 5 hours to 25 hours depending on the athlete and terrain. What do those durations have in common? They are–and this is a scientific term–really freaking long.

In the RFL zone, most athletes are primarily relying on fat oxidation around aerobic threshold and below. And like all events longer than a couple minutes, the aerobic foundation is the most important element of performance. Time on feet and mileage matter, though it’s less about accumulating massive totals than being consistent, with enough low-level easy activity to develop the aerobic system via increased capillarization and more efficient metabolic processes.

Takeaway: The plan includes plenty of easy running and hiking, with optional doubles and cross-training.

Muscular resilience

Here is the trickiest part of 50 milers, and the part that is most event-specific. A flatter 50 like Tunnel Hill is a very different stress than a mountainous 50 like Ouray, or a steeply rolling 50 like Lake Sonoma. The temptation is to go all-in on race-specific training, but that might not be the best approach to long-term growth.

Overemphasizing flat training could undersell an athlete’s ability to run fast on the flats after a few hours. As the muscles fatigue, ground contact time increases, leading to a greater level of eccentric muscle contractions (when the muscle lengthens under load). So even for flat courses, some vert can be helpful to induce those adaptations to eccentric muscle contractions.

Overemphasizing steep training could cause an athlete to slow down via the “climbing paradox,” when output goes down to account for the higher muscular strain from going uphill and downhill.

Fortunately, you can have your cake and eat it too. Or you could rub your cake onto your nipples. It’s your cake, you can do what you want with it. Speed and strength can form a feedback cycle that allows for peak performance on any type of course.

Takeaway: Weekday runs focus on speed and output, with weekend trail runs being more race-specific, plus consistent strength work. In the final month, specificity becomes a greater focus.

The 50-Mile Plan

This 50-mile intermediate/advanced/pro plan is designed for athletes that already have a base, stemming from requests by readers (if you have requests for another type of plan, let us know!). It can work for advanced 50Ks or marathons as well, or even 100Ks with a greater emphasis on weekend long runs.

If you’re more interested in building base for long-term growth, see this 12-week base plan for somewhere to start. And if looking for a better intro plan, see this 12-week plan on training for your first ultra over 50k or this 12-week plan on training for your first half or under. An amazing book is Running Your First Ultra by top coach and athlete Krissy Moehl. Here is the 100-mile plan that Andy used, which can be used for mountainous 50 milers as well.

Biggest disclaimer: every athlete is unique, so what works for you may be totally different than what you see in a general plan. That is an exciting opportunity for training experiments! But it can also be frustrating if you see a training plan that has elements that aren’t optimal for your unique background and physiology. This plan is meant as a starting point for intermediate/advanced/pro 50-mile training based on what has worked for many athletes we coach, but if you need to change it up, that is just a great recognition of your exciting uniqueness.

IMPORTANT POINT: Each day is given as a range of miles, with the design being to stay at the low, middle, or high end without going back and forth too much week to week. Start at the lower end of the range unless you have done higher mileage in the past. Think of it as 3 different plans in one! Low end of range = intermediate. Middle of range = advanced. Top of range = super duper advanced athletes that prefer higher volume.

The lower range starts at 18 miles per week and peaks at 52 with most weeks around 35, while the high end gets up to 101 miles and is usually around 70-80. Athletes can add cross-training and hiking on top of that total on the days specified.

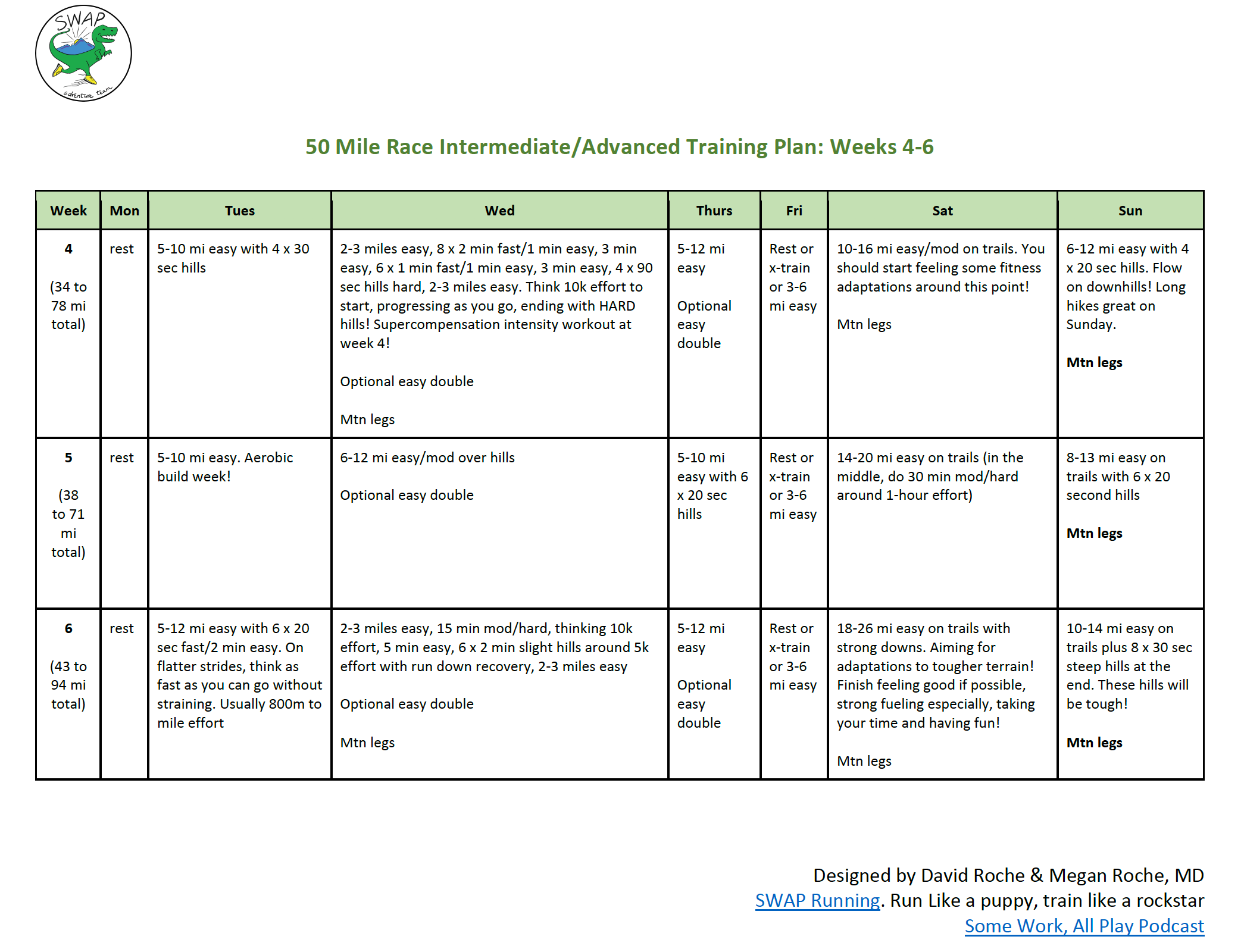

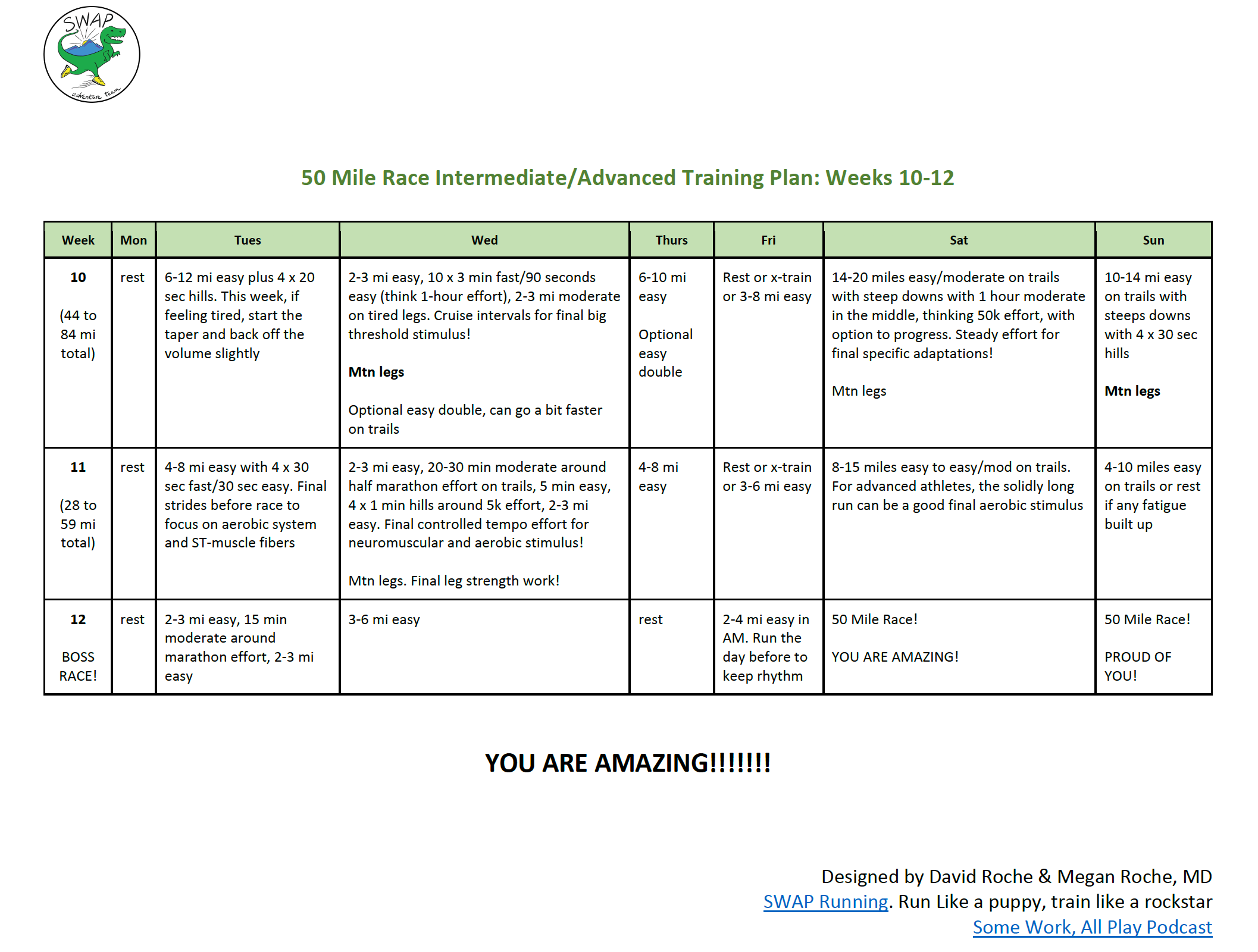

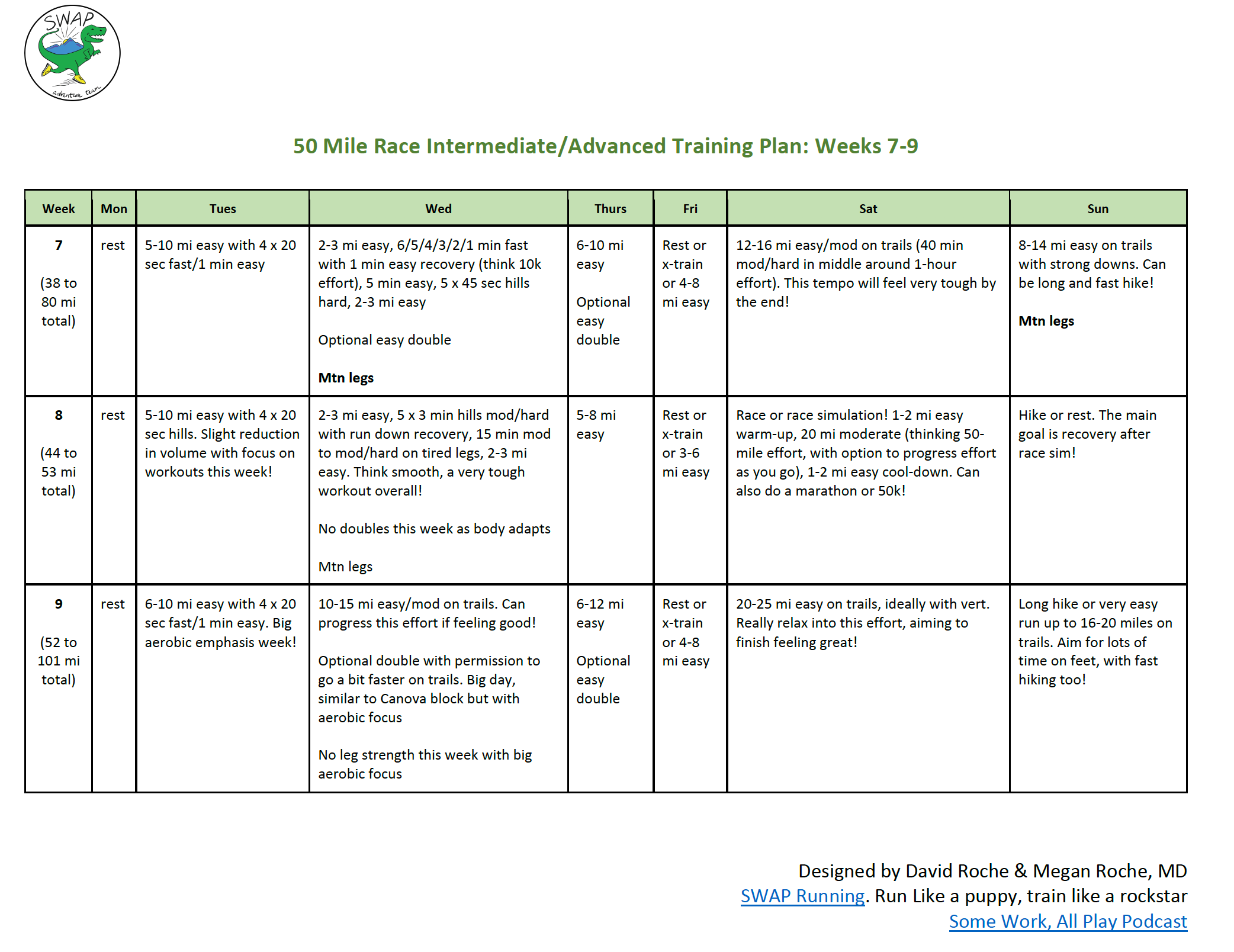

Weeks 1-4 build base and introduce speed, while extending long runs and adding vert. Week 5 is an aerobic build week that increases volume with a bigger weekend. Weeks 6 and 7 continue the upper-end adaptations while keeping volume high. Week 8 involves a hard workout and race simulation or training race. Week 9 is peak volume, week 10 dials in running economy adaptations, and weeks 11 and 12 are the taper. During the taper, reduce miles if you are fatigued or the training was more than you have done in the past.

The long runs don’t exceed a marathon as a max option because the risks often outweigh the benefits in longer, breakdown-heavy days. Back-to-back long runs and long run tempos will get many of those benefits with less risk of injury. There may be some neuromuscular or muscular benefit to racing a marathon or 50k 4 to 8 weeks before your 50, but it’s not necessary, and the plan has a 20-mile focused effort penciled in 4 weeks out.

Instead of massive long run volume, seek out vert if you can on your weekend runs/hikes in particular. That steeper uphill and downhill stimulus will add resilience for the later stages of the 50. Lower-body strength work is included in the plan, and if you do not currently do upper-body work, read this article and spend a couple of minutes on it a day through push-ups and/or chin-ups.

Other Things to know:

- Be careful increasing mileage, and always rest or x-train at the first sign of injury. This is a perfect-world plan, and it’s designed to allow for missed time.

- You can use run/hike strategies to do the designated mileage. Hike with purpose when needed (form tips here), since hiking is an important part of most ultras. And when that’s not possible, remember a five-minute run/hike counts too.

- All of the numbers in the plan are general guidelines, rather than specific rules. Mix it up to fit your life and background. It’s always OK to miss a day or two or sub in an easy day.

- Do light rolling/massage and optional light stretching daily, and make sure you’re always eating enough food.

- The plan is designed for an athlete that wants to optimize their potential, but no single day is too important. Prioritize happiness and health above all else. Before starting any new routine, talk with a doctor or medical professional. This is not specific coaching advice for your individual history, but a general template to help you design your own plan. It’s always best to work one-on-one with a coach.

- You are loved and you are enough, just as you are, always. Not directly related to the plan, but an important background principle.

Key resources:

- 4-Minute Wake-Up Legs warm-up routine (before all runs)

- 3-Minute Mountain Legs strength routine (when noted). Important: when “Mtn legs” is in bold, you can do the Speed Legs routine

Terminology:

Rest days: you can be active, but no pounding on your legs. Rest day routine article

Easy runs: relaxed and effortless, but can progress to steady running when you feel good as long as it’s not every easy run.

Aerobic build week: a semi-structured week with aerobic emphasis

Cross-training: bike, elliptical, swim or hike ideal. Cross-training article

Hill Strides: powerfully efficient on moderate grade. Hill strides tutorial article

Flat Strides: as fast as you can go without straining

Tempo runs: around 1-hour effort, relaxed and not too hard

Uphill treadmill doubles: optional training elements for climbing practice

Access a printable PDF of the plan here! You are AMAZING!

David Roche partners with runners of all abilities through his coaching service, Some Work, All Play. With Megan Roche, M.D., he hosts the Some Work, All Play podcast on running (and other things), and they wrote a book called The Happy Runner.