12-Week Intermediate/Advanced Base-Building Training Plan

(Photo: Alex Gorham/Unsplash)

In my first-ever road half marathon, I rocked a training cycle and ran a 1:21. I was so proud of myself! I remember digging so deep that I was curled up in the subway car on the trip back to my dorm room, my internal organs starved of blood flow. At the start of that training cycle, my range of potential outcomes may have been 1:19 to 1:26, depending on the training approach, assuming I stayed healthy and consistent. I crushed training and got near the fast end of the range. HECK YES.

Fourteen years later, I have run trail half marathons, with technical sections and climbing, 5-10 minutes faster. If I were to race a road half again, my base would set me up for a range more than a minute per mile faster.

Those long-term changes happen in the unglamorous grind, not in specific training cycles for events. So it’s odd that there are very few training plans that focus on background principles of long-term aerobic growth, rather than race specificity (my own plans included). After all, your potential for year-over-year growth makes anything else look relatively marginal.

Let’s change that today. It’s time to grind with this base-building plan.

4 Base Principles

I think that base training has been simplified to the point of being actively counter-productive for some athletes in large swaths of online training literature. It’s not just about aerobic development, stacking up work in Zones 1 and 2 (in a 5-Zone model) without developing speed, and hoping for magical improvement. Base is about methodically improving how the cells of the body metabolize fuel and shuttle lactate, while increasing the amount of output that can be generated by each stride, combining purely easy running with moderate aerobic efforts and constant speed reinforcement. The plan relies on 4 principles that we talked about in detail on our podcast.

One: Low-level aerobic time below the first ventilatory threshold (~Zones 1 and 2 in 5-Zone model) improves fat oxidation, increases capillaries around working muscles, enhances recruitment of Type I slow-twitch muscle fibers, and may improve mitochondrial function.

This is the point that you’d probably guess–stacking up aerobic work over time. Easy training is a core principle of all endurance growth, due to how it improves the cellular-level context for fatigue management and can be developed almost indefinitely.

RELATED: A Theory About Building Speed While Doing Long Races and Ultras

However, it’s not just about going easy all the time. There are probably a thousand people reading this who have tried pure “MAF training” where they run at a heart rate of 180-age, with promises of faster running over time, only to get slower and slower. The problem is that most athletes will end up becoming output-limited, and unless they simultaneously focus on power development, easy training will get less efficient as the systems-level biomechanical processes are not equipped to actually use the cellular level aerobic changes.

While most training should probably be around 80% easy, base training can be 90-95% easy, with the faster work focused on improving mechanical output. Here, “easy” generally means below the first ventilatory threshold, where you can talk in complete sentences and feel no resistance most of the time, but with permission to increase the pace to easy/moderate or steady on days when things feel good. Cross training adds aerobic work without impact, and will be optional throughout the plan.

Two: Developing an aerobic base on top of a speed foundation allows that low-level aerobic time to translate to more economical outputs.

Similarly, starting the base-building process with poor speed is like trying to chop down a tree with an unsharpened ax. You’re about to take 1,000 swings – better make them count.

Applying these types of principles year-round interspersed with specific training for races can let an athlete go from playing with marginal gains to contemplating decades-long breakthroughs.

The plan starts with a few weeks of reinforcement of output around VO2 max, and periodic reinforcement throughout the training cycle. That will make sure that athletes aren’t starting from a place of inefficiency.

Three: Constantly reinforcing top-end speed builds mechanical power without risking aerobic regression.

The problem with purely easy activities is that they don’t involve much power development. Do that for long enough, and you have an aerobic system that can write massive checks, but with legs that can’t cash them.

Throughout the plan, hill strides and flat strides build that output. Given that they are short, there is little risk of counteracting aerobic development, which is a peril with an excessive amount of work in upper Zone 4 and Zone 5 in a 5-Zone model.

Four: Moderate threshold work between the first and second ventilatory thresholds (Zones 3 and 4 in 5-Zone model) improves lactate shuttling and enhances aerobic development.

Later in the plan, there is a heavy dose of moderate and threshold running, allowing the body to improve how it clears moderate amounts of lactate. By the end of the plan, we should have created an aerobic monster, who can run easily all day without too much fatigue. But that’s just the start of it. That aerobic monster could also pick up the pace effortlessly, running an hour or two at steady efforts without much heart rate drift. And when it comes time to throw down, the monster can move fast, with pure power that feeds back into more economical easy and moderate running, and quality workouts in specific training to come. Following these 12 weeks, an athlete would be ready to do hard specific training for a peak road or trail race, or would be prepared for great performances at races up to 50 miles with just a couple specific efforts.

RELATED: Easy/Moderate Fartlek Workouts For Improving Endurance

Essentially, this plan embodies the background aerobic principles inherent in all advanced training philosophies. Applying these types of principles year-round interspersed with specific training for races can let an athlete go from playing with marginal gains to contemplating decades-long breakthroughs.

Plan Logistics

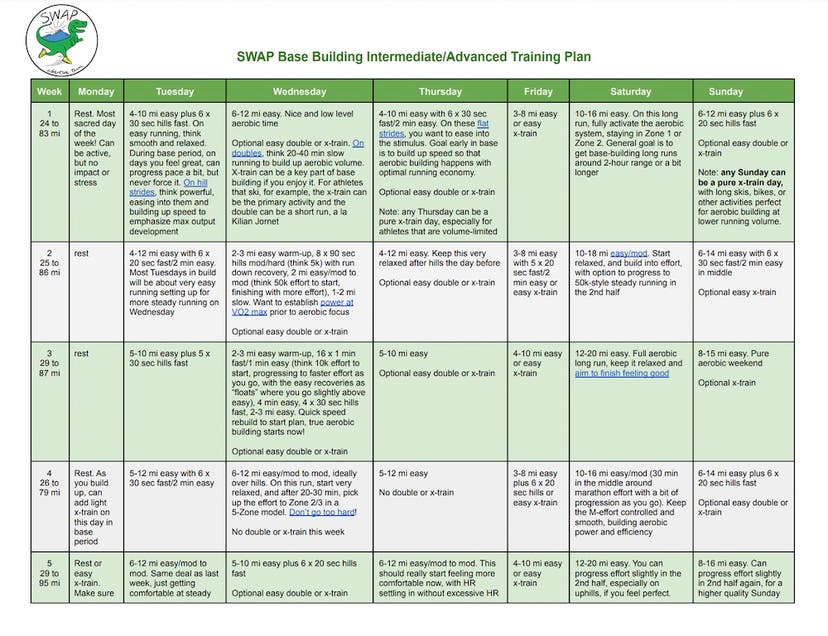

As with all of these free plans, I prescribe each day as a range of miles, with the design being to stay at the low, middle, or high end without going back and forth too much week to week. Start at the lower end of the range unless you have done higher mileage in the past. Think of it as 3 different plans in one!

- Low end of range = intermediate.

- Middle of range = advanced.

- Top of range = super duper advanced athletes that prefer higher volume.

The lower range starts at 24 miles per week and peaks at 34, with plenty of cross training options, while the high end gets up to 100 miles and is usually around 80-90. Weeks 1-3 build up volume and VO2 output. Weeks 4 and 5 focus on the addition of steady running. Weeks 6 to 12 increase the aerobic training stress while improving output around aerobic threshold. You can start in week 6 if you are rolling into base-building with good fitness, or confine the plan to the first 6 weeks if you have a compressed time window for training after an offseason.

Other Things To Know

- Be careful increasing mileage, and always rest or cross-train at the first sign of injury. This is a perfect-world plan, and it’s designed to allow for missed time.

- You can use run/hike strategies to do the designated mileage. Hike with purpose when needed (form tips here). And when that’s not possible, remember a five-minute run/hike counts, too.

- All of the numbers in the plan are general guidelines, rather than specific rules. Mix it up to fit your life and background. It’s always OK to miss a day or two or sub in an easy day.

- Do light rolling/massage and optional light stretching daily, and make sure you’re always eating enough food.

- The plan is designed for an athlete that wants to optimize their potential, but no single day is too important. Prioritize happiness and health above all else. Before starting any new routine, talk with a doctor or medical professional. This is not specific coaching advice for your individual history, but a general template to help you design your own plan. It’s always best to work one-on-one with a coach.

- Ideally do the 4-Minute Wake-Up Legs warm-up routine before all runs.

- Base period is a great time to focus on strength work, and we have a time-crunched plan that is just a few minutes a day, and a more comprehensive Strength Work Cheat Sheet for advanced athletes.

- You are loved and you are enough, just as you are, always. Not directly related to the plan, but an important background principle.

Click Here to Access the Plan (PDF)

Developing aerobic base in a speed context makes champions. Let’s do this!

David Roche partners with runners of all abilities through his coaching service, Some Work, All Play. With Megan Roche, M.D., he hosts the Some Work, All Play podcast on running (and other things), and they answer training questions in a bonus podcast and newsletter on their Patreon page starting at $5 a month.