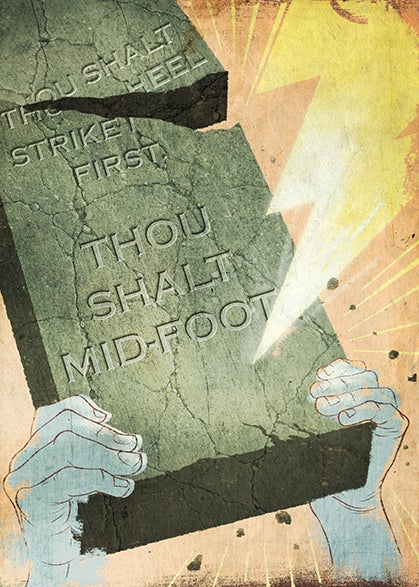

Heel Strike, You're Out!

How does the new midfoot-strike theory hold up on the trails?

This article originally appeared in issue March 2010 issue.

Illustration by Kevin Howdeshell

Since the era of the legendary Bill Bowerman, former renowned coach of University of Oregon Track and Field from 1949 to 1972 and founder of Nike, it has been widely regarded that the best running technique for athletes is one in which the heel strikes the ground first. But, recently, some running experts have spoken out against heel striking, promoting instead a mid-foot strike, which they believe is more economical and causes fewer injuries. The ensuing debate has raised more questions than answers.

Ultimately, you must decide which technique works best. Injuries and race times may depend on it.

Don’t Change a Thing

In a study conducted at UMASS by the laboratory of Joseph Hamill, PhD, 10 recreational runners, all heel strikers, were taught to run landing on their mid-foot. The study measured the oxygen consumption of the athletes when they landed on their heels and again with a mid-foot strike. The results confirmed what many had thought all along: that foot strike does not affect running economy.

“We concluded that there was no advantage to changing from a rear-foot to a fore-foot pattern,” says Dr. Hamill. “I think the pattern that one uses is highly dependent on the individual. There is no correct way to strike the ground for everyone.”

Another study, published in the Journal of Strength and Conditioning, in 2007, analyzed the foot strikes of all elite runners at the 2004 Sapporro International Half Marathon. Setting up a high-speed camera at the 15K mark, Japanese scientists found that 75 percent of the elite athletes landed on their heels, 24 percent on their mid-foot and one percent on their forefoot.

“There’s no [scientific] evidence that heel strikers are injured more, no evidence that mid-foot runners are faster and perform better than heel strikers, and so the ultimate question is: Why would you want to change your foot landing?” says Ross Tucker, PhD and co-writer of sportsscientists.com. “My advice … is to forget about the possibility that you’re landing ‘wrongly,’ and just let your feet land where and how they land.”

Go Natural

Despite a lack of supporting evidence, promoters of the mid-foot strike remain convinced that they are onto something. Inexorably tied to the mid-foot hypothesis, barefoot running, which forces athletes to land on the balls of their feet, makes a strong case for itself. In fact, it has yielded positive results in the United States, most notably at Stanford University.

“I can’t prove this,” says Stanford cross-country and track coach, Vin Lananna, “but I believe when my runners train barefoot, they run faster and suffer fewer injuries.” This belief eventually prompted development of the Nike Free, a minimalist shoe meant to simulate barefoot running.

Christopher McDougall, author of the recent book Born to Run (see excerpt on page 46), mounts a compelling argument for the mid-foot strike as well. He argues that running on our heels is not natural, and cannot be performed without our own modern invention, the running shoe, which he claims is in fact the cause of many injuries. Running without padded shoes, he says, reveals our “natural” running form.

“Before the invention of a cushioned shoe, runners through the ages had identical form: Jesse Owens, Roger Bannister, Frank Shorter and even Emil Zatopek all ran with backs straight, knees bent, feet scratching back under their hips,” says McDougall. “They had no choice: the only shock absorption came from the compression of their legs and their thick pad of mid-foot fat.”

Danny Dreyer, running coach and author of Chi Running, promotes mid-foot running and asserts that running form can be best explained by the laws of physics. “A basic understanding of physics will tell you that any time you strike the ground in front of your center of mass, you’ll create a force in the opposite direction to your movement,” says Dreyer. “When you heel strike you’re putting on the brakes with every stride, which creates impacts to your body from the lower back to your plantar fascia. When you strike with a mid-foot behind your center of mass, it significantly reduces any chance for impact or braking to happen.”

“Most coaches and scientists like to think that we can’t beat the Kenyans because of their talent,” says Dreyer. “In truth, we will never beat the Kenyans until we start using the same highly efficient biomechanics they are using … which includes a significant lean and an immense amount of relaxation.”

Eric Blake, a member of the U.S. Mountain Running Team and the head coach of Central Connecticut State University’s Cross-Country and Track programs, supports McDougall and Dreyer’s opinions, saying, “When you land on your heel, your mid-foot still has to touch and take off. The end result is that you end up being on the ground longer when you heel strike, and that is never a good thing,” says Blake. He also adds that the heel strike puts more pressure on runners’ legs. “You want that force moving forward, not back into your legs,” he says.

Ian Hobler, an elite Canadian trail runner, promotes the mid-foot strike as well, which he believes increases running efficiency and reduces stress on the body. “Regardless of how far or fast I’m running, I try to land softly and have my feet on the ground for as little time as possible, so I have to land on my mid-foot,” says Hobler. “My entire foot can absorb the shock, followed by my knees and hips, which are more aligned bottom to top with a mid-foot strike than with a heel strike. This soft landing spares my muscles, connective tissue and joints from undue strain.”

Several running companies have also jumped on the mid-foot bandwagon, designing products that contrast with the common, heavily padded motion-control shoes. Creating a product that essentially forces the foot to rely on its own evolutionary design, Vibram has developed a “shoe” called FiveFingers, basically a shoe sock offering zero cushioning or support, only minimal protection.

Similarly, Newton Running has developed its entire line of running shoes based upon the mid-foot strike concept. “Recent research and news reports are confirming what those close to the sport have known for years: running shoes with thick midsoles, extensive anti-pronation devices and large heel crash pads don’t prevent injuries,” says Danny Abshire, co-founder of Newton Running. “The tenets of good running form include running with short strides and a quick cadence, landing lightly on the mid-foot-forefoot area, and quickly lifting your foot off the ground instead of pushing off with excessive muscle force. A slight forward lean and a relaxed arm swing are also key components.”

It’s Your Call

With so many different ideas and opinions from elite athletes and experts in a variety of fields, runners are faced with a tough decision when they hit the trails: run with a heel strike or change to a mid-foot strike. One piece of advice that seems consistent among elite runners is simply for individual runners to do what feels right. “I think that the difference we are discussing is more than just foot strike,” says elite trail runner Rickey Gates. “We are talking about two different running styles. Try out both styles and pay close attention to what the rest of your body is doing.”

“In my opinion, running is a highly subjective science, so experiment to figure out what works best,” adds Hobler. “If a heel strike keeps you happier and more successful than a mid-foot strike, why change?”