8-Week Road Marathon Training Plan For Trail Runners

Fitness is fitness. Or to be more precise, long-term running economy development should benefit performance in all disciplines, whether a trail race or ultramarathon, road marathon or track mile, OCR race or long hike. We all have a beast inside of us, it just needs to be unleashed.

Road marathon training is one great way to let our amazing talents shine. And those benefits are tied specifically to a universal truth, known since Pheidippides hit a quite sturdy wall—road marathons are really, really hard.

In a road marathon, athletes rely primarily on the interaction of aerobic threshold (AeT, the effort level where the body switches from mainly fat to mainly glycogen for fuel, which can be sustained for a few hours, with variation), lactate threshold (LT, around 1-hour effort), and muscular endurance. Aerobically, the goal is to get AeT to compress up toward LT. Coach Renato Canova and others that have revolutionized the approach to road marathon training generally try to bring sustainable effort levels all the way to the ceiling, while also raising the ceiling.

RELATED:Run Faster On Trails With Power Hill Strides

That process starts by developing an aerobic base with easy and some steady running, along with max muscular and cardiac output via strides and hills. Those basic principles popularized by Coach Arthur Lydiard back in the 1960s are true of any base build, even as their specific application has evolved through coaching approaches over time. Next, improving velocity at VO2 max and LT through intervals and tempos allows athletes to sustain faster paces for longer. Incorporating long, steady runs that stress lipid metabolism and upper-end aerobic output creates an ability to sustain relatively high efforts for longer. Then it’s all brought together with marathon-effort workouts and long runs that allow athletes to sustain higher outputs and heart rates without burning through all of their glycogen.

Get strong and fast, push back the bonk, adapt the musculoskeletal and metabolic systems to be able to run relatively hard for a long time. Now those are some damn good adaptations. Research and training theory back up the effectiveness of focused marathon training for trail runners.

The fastest runner will usually be the best climber.

A 2018 study in the European Journal of Applied Physiology found that at any given time, uphill running economy and level ground running economy are strongly correlated. Road marathons are perhaps the purest tests of economy, since even a hint of inefficiency (going a bit too fast relative to energy consumption) will make itself known in a terrible way at mile 20. While uphill running involves slightly different biomechanics and internal mechanical workload (see 2017 review study in Sports Medicine), those differences likely get smoothed out with just a bit of specific training. Because a strong road marathon maximizes total aerobic output, there should be benefit for any event where aerobic output is the limiter (from a 5K to a 200+ miler).

And training theory backs that up, with oodles of athletes that excel in trail racing coming from road or track backgrounds. The fast marathoner won’t always win on the climbs. But I know who I’m betting on.

Training implications: Speed training should improve flat and uphill running on trails. And the correlation goes both ways—some trail running and climbing should improve aerobic output on flat roads too. You don’t need to forego trails entirely (or even much at all) to run really fast on roads.

With some specific training, the fastest runner should be a good descender too.

RELATED: Training To Be A Strong Downhill Runner

The 2018 study also found correlation between level running and downhill running, though those associations are likely much less strong on steep and technical terrain. On those types of downhills, aerobic output is relatively low. The limiters end up being musculoskeletal resilience to eccentric contractions (when the muscle fiber lengthens under load, primarily on steeper grades) and neuromuscular/biomechanical practice.

There isn’t much agreement on what can be done to become a blazing fast technical descender, though form, practice, and fearlessness can’t hurt. Nor can being really fast generally—becoming your fastest self gives a lot more margin for error, as long as the error doesn’t involve tripping off a cliff. As always, dying is a sub-optimal training adaptation.

Training implications: Reinforcing trail running throughout a road marathon cycle can keep resilience high, while also supporting practice-based adaptations. And all trail runners should probably do some running on terrain that allows them to maximize output, even if it’s just a smooth and rolling trail.

RELATED: A Training Plan To Run 100 Miles

Fatigue resistance developed in road or track training should benefit ultramarathon performance.

If you follow enough road marathons, you see a pattern. Somewhere from mile 16 to mile 22, there is an invisible wall that much of the field runs into like they’re doing an impression of a sugar-free Kool Aid man. What is happening?

It’s tempting to say “inadequate training.” I don’t think that’s it. I’d argue that any athlete who runs a few times a week and does a few long runs in training can cover the distance without fading too hard. My answer is usually something else—“started too fast.”

The magic of mile 16 to 22 is the duration of running until that point. At 90 minutes to 4+ hours, the body is stressing glycogen stores and our old friend aerobic threshold. Exceed aerobic threshold too long or fail to properly refuel, and the gas tank approaches empty. Studies show performance starts to deteriorate even before our bodies sputter to a stop. Often, what feels like severe muscular fatigue is just muscles deprived of what they need to maximize performance. The wall is protecting us from catastrophic bodily failure. Stupid/helpful wall!

Or maybe the fade is related to eccentric muscle contractions, where duty factor increases as the race goes on (more ground contact time and knee-sink on each step), causing more micro-damage. Or it could be neuromuscular, with sub-maximal contractions weakening even with full fuel availability and limited measurable muscle damage. No matter what causes the fade, it all gets back to the murky science of fatigue resistance.

Last month’s article on fatigue resistance goes over some possible options to improve performance in a high-fatigue context, but one that wasn’t mentioned was much simpler: push to the absolute edge in training, where you can learn about your body and brain. Training theory-wise, show me a marathon GPS file with a negative split, and I’ll show you an athlete that can excel in ultras with some practice.

Training implications: Difficult workouts like those in the plan could have benefits in performance at all distances. Since vert may play a role in fatigue resistance, doing some trails year-round may help as well.

RELATED:An Expert Training Plan For Your First 50K

Plan Rationale

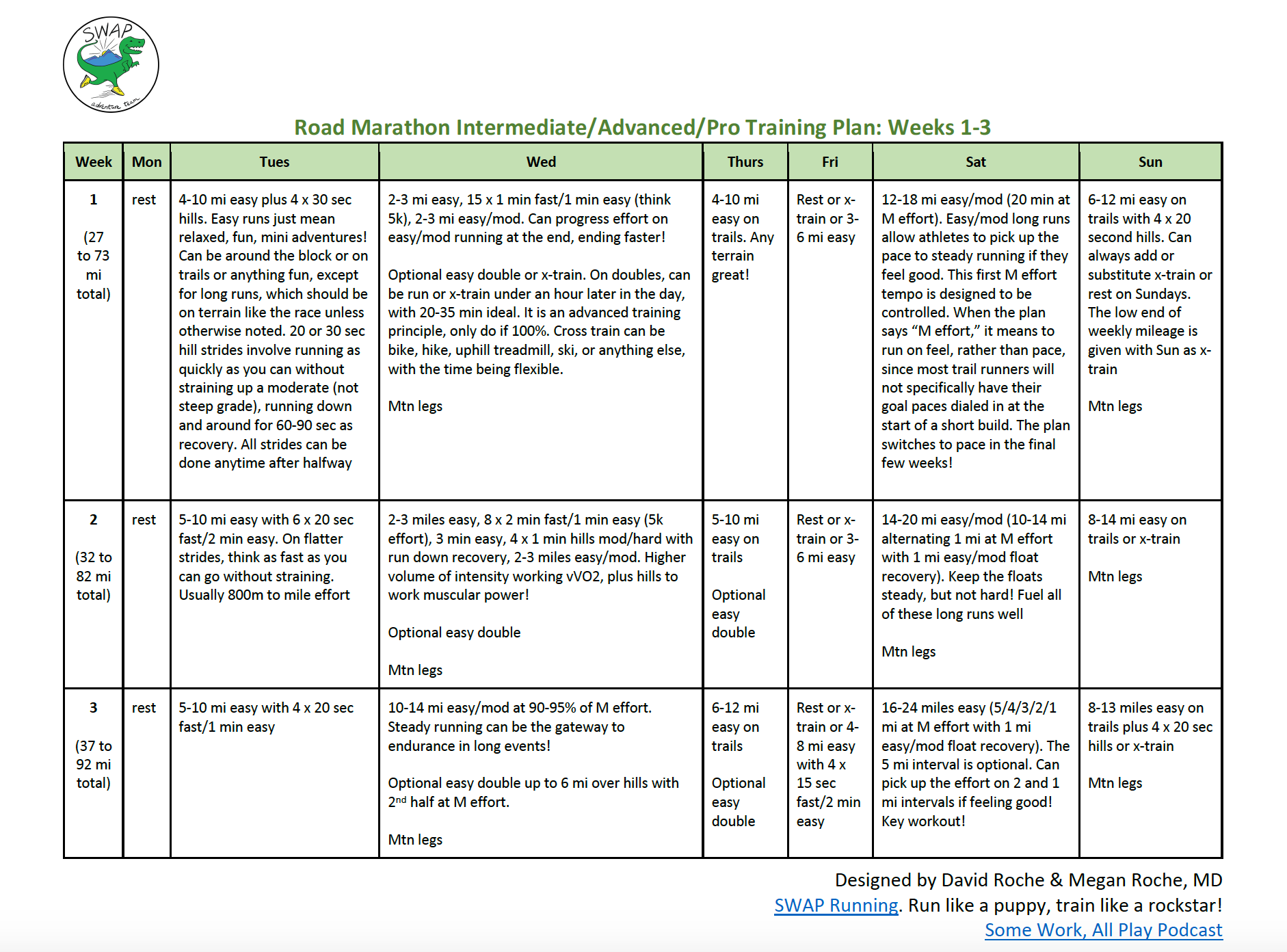

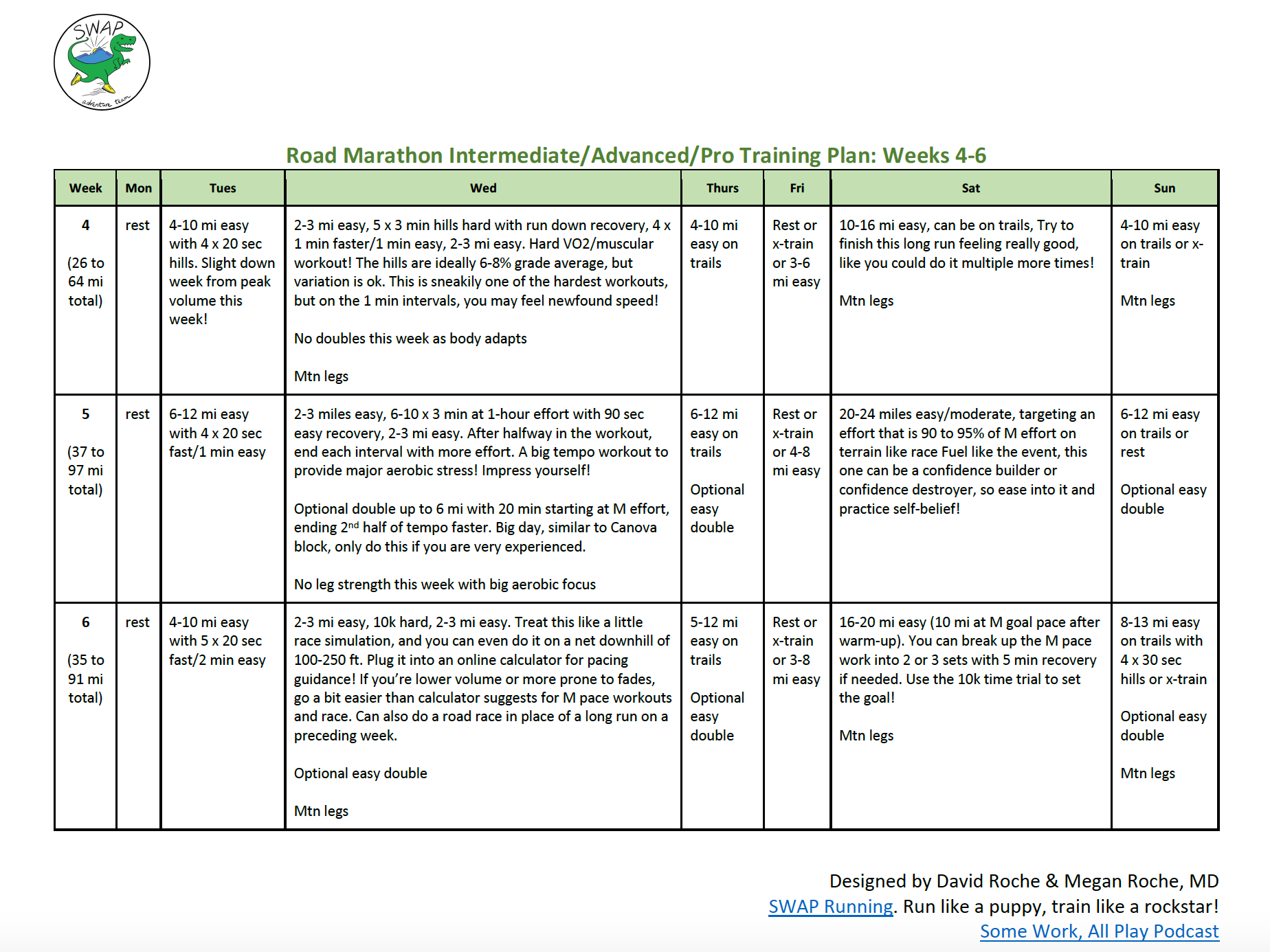

This marathon plan is in response to numerous requests from readers to help them prepare for a dalliance into road training. The plan is just 8 weeks to account for shorter builds by athletes balancing trail goals and road training. Start it only when you have a good base of endurance and speed (here’s a 12-week plan for that, and another 6-week plan for speed). The first 4 weeks of either plan would be an ideal way to make it a typical 12-week build.

You can throw this schedule in before, during, or after trail season, or just take the last few weeks of it for the final specific build. Even the first few weeks could be a good stimulus for athletes looking to spice up their training mid-season.

The plan is designed for intermediate to advanced athletes, with a range of miles on each day. Think of it as a few different plans—the low end of the range being a good intermediate default, and the high end and optional workouts being for advanced athletes or pros.

Things To Know

- Be careful increasing mileage, and always rest or x-train at the first sign of injury.

- You can use run/walk strategies to do the designated mileage. And when that’s not possible, remember a five-minute run counts too.

- All of the numbers in the plan are general guidelines, rather than specific rules. Mix it up to fit your life and background.

- Do light rolling/massage and optional light stretching daily, and make sure you’re always eating enough food.

- Fuel the long runs adequately, with 200-300 calories per hour plus fluid.

- The plan is designed for an athlete that wants to optimize their potential, but no single day is too important. Prioritize happiness and health above all else. Before starting any new routine, talk with a doctor or medical professional. This is not specific coaching advice for your individual history, but a general template to help you design your own plan. It’s always best to work one-on-one with a coach.

- You are loved and you are enough, just as you are, always. Not directly related to the plan, but an important background principle.

Terminology

Rest days: you can be active, but no pounding on your legs. Rest day routine article

Mtn Legs: The 3-Minute Mountain Legs routine, done after runs on the days noted

Easy runs: relaxed and effortless, but can progress to steady running when you feel good as long as it’s not every easy run.

Aerobic build week: semi-structured week with aerobic emphasis

Cross training: bike, elliptical, swim or hike ideal. Cross-training article

Hill Strides: powerfully efficient on moderate grade. Hill strides tutorial article

Flat strides: the fastest you can go without straining

Tempo runs: around 1-hour effort, relaxed and not too hard

Here is a free download, and below are screenshots. YOU ARE AMAZING!

David Roche partners with runners of all abilities through his coaching service, Some Work, All Play. With Megan Roche, M.D., he hosts the Some Work, All Play podcast on running (and other things), and they wrote a book called The Happy Runner.