6-Week Training Plan To Improve Speed

Man and woman running in the mountains

Over time, VO2 max has become overstated. As a coach, I don’t care about an athlete’s VO2 max. I don’t care about how much oxygen they are able to use during exercise, which is largely genetic and won’t change that much for an experienced athlete. What I care about is what an athlete does with the oxygen they have.

The VO₂ max test I recommend is this one: imagine that your number is off the charts, and train accordingly. That is how you’re going to improve your speed. But before we get there, let’s dive a little deeper into how VO2 max works.

VO₂ Max Context

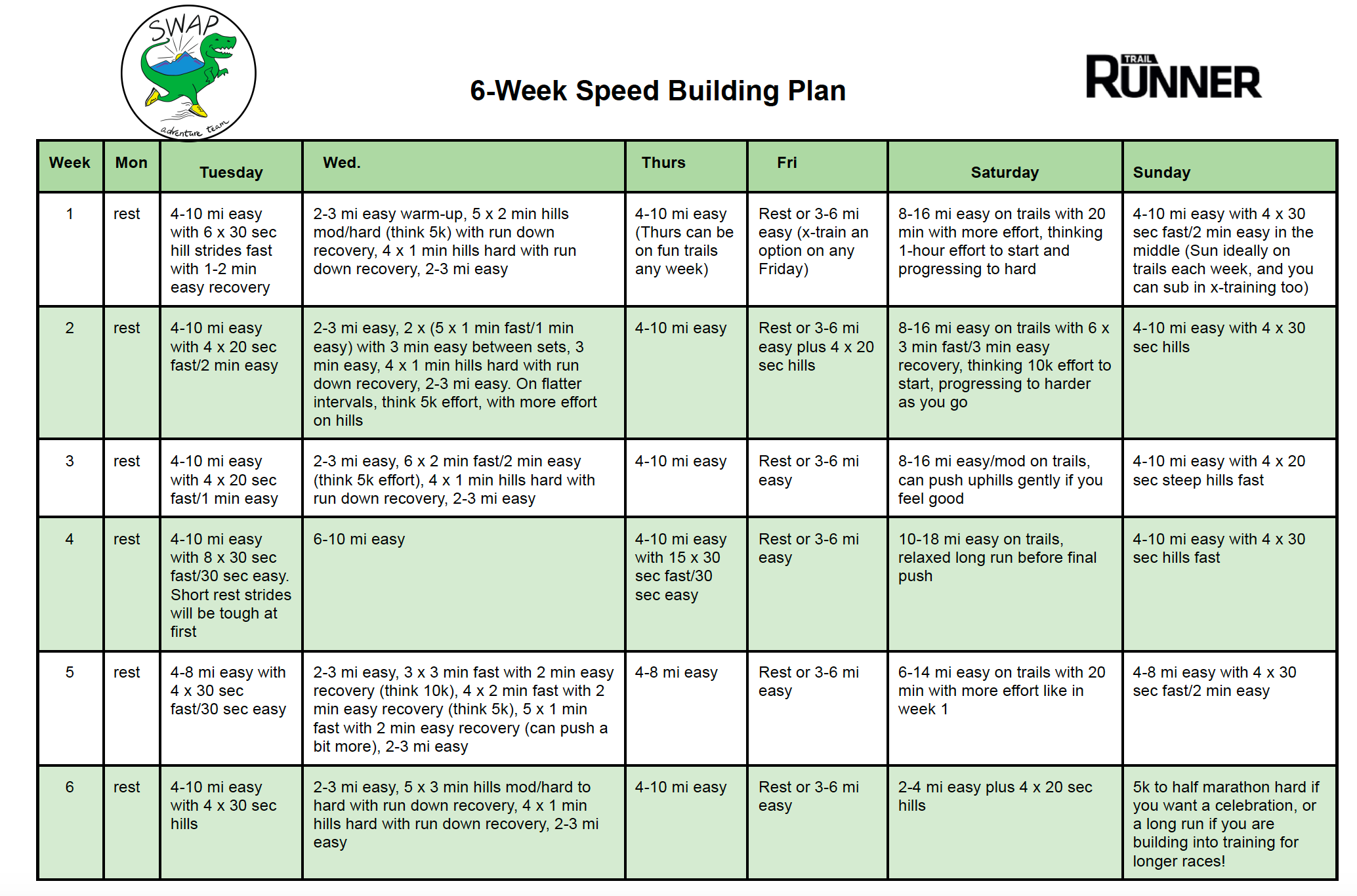

That “train accordingly” advice is how this article concludes, with a 6-week sample plan to optimize your upper-end running economy to improve performance at all distances. But first, a slight digression on why I am not concerned with that VO₂ max number, which informs the sample plan’s workouts and relatively short duration. And by “slight digression,” I mean 2 pages. This must be what George R. R. Martin feels like when he writes about dragons.

VO₂ max is the maximum oxygen uptake during intense exercise, usually corresponding to an effort that lasts 7 to 11 minutes (with variation around those numbers) depending on how it’s measured and athlete background. The number rises rapidly upon the start of training programs (either at the beginning of an athletic career or after a layoff), particularly training involving focused intensity. The absolute peak of that genetic potential is relatively young, with gradual reduction often starting in the late 20s or early 30s. Draw a scatterplot of VO₂ maxes against race results for the general population, and there will be some general correlation.

So why don’t we turn races into VO₂ max contests?

The hypothetical scatterplot mentioned above is deceiving. While there may be some cross-population correlation between VO₂ max and race outcomes, the association breaks down as you zoom in on similar cohorts of athletes. Think of it like a plot of how far people can hit a golf ball at a driving range. Yes, someone like me whose golf swing is an affront to nature won’t drive the ball far and will also get beaten by an experienced golfer. But among the experienced golfers, drive distance in isolation is not highly predictive of outcomes, and it involves many confounding variables (like who practices consistently over time).

With VO₂ max, the offset is based on how the body actually translates oxygen uptake into speed. First, the aerobic system is not just reliant on max consumption of oxygen–outside of very short events, the limiter on performance is dominated by more aerobic processes anyway. In events longer than middle distance track and road races, aerobic threshold (a proxy for overall aerobic development, around 2 to 3 hour effort) and lactate threshold (a proxy for fatigue tolerance, around 1 hour effort) are more important. The coolest part for long-term growth? Both of those metrics are highly trainable, with genetic starting points that can get swallowed up by smart training. VO₂ max, LT, and AeT may have some correlations (since the body doesn’t work in neat silos), but the VO₂ max number itself is rarely going to be the limiter for an experienced athlete in road and trail races.

But here’s where the rubber really hits the road. Why do we even measure VO₂ max? As outlined by Coach Steve Magness in this article from 2009, the history of physiological measurements largely depends on what we can reliably measure, rather than what has specific value for informing training. That’s where velocity at VO₂ max comes in (or climbing speed at VO2 max). By focusing on speed, it turns a measure of uptake into a measure of output. Running economy is the amount of energy used at a given output, and it’s so much more complex than a raw VO₂ max number even when that effort level is being practiced.

How does the body turn the oxygen input into speed output?

Seriously, I’m asking.

It’s immensely complex and there’s no single path, incorporating the musculoskeletal system, biomechanical system, neuromuscular system, endocrine system, early 2000s rock metal group System of A Down (I’m guessing), etc. While the aerobic system usually takes a longer time to adapt after initial gains, most of these systems can move a bit more rapidly. In the case of the neuromuscular system in particular, it might be as short as a few training sessions, though it’s debated.

For example, a 2018 study in Physiology Reports had 20 trained athletes do 10 sessions of 5 to 10 x 30 seconds fast in a 40-day training cycle where total training volume was reduced by 36 percent. After the intervention, 10K performance improved by 3.2 percent. Perhaps most interestingly, VO₂ max didn’t change at all (and it actually had a non-significant decrease). Instead, the athletes improved by two percent in their velocity at VO₂.

In other words, their aerobic systems had not improved, they were just going faster with the oxygen they had. The progress was based in some combination of their musculoskeletal, biomechanical, and neuromuscular systems. I only wish that study was available in lotion form so I could apply it to my pores before bed.

On a similar note, a 2006 study in the International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching tracked Paula Radcliffe’s metrics throughout her career, finding that her VO₂ max actually decreased from when she was a champion junior athlete, but her running economy improved by 15 percent. VO₂ max and running economy may be connected early in a runner’s career, but after that what matters is consistent training to put out power more efficiently. The starting point does not determine the ending point.

And that’s where this article comes in.

A common mistake in training is to focus on the slower-to-adapt aerobic system at the expense of how the brain and muscles translate that energy source into output. VO₂ max-focused training may be a primary culprit.

Many studies find that the best way to improve VO₂ max is to go REALLY REALLY HARD. As a result, many athletes that run longer distances avoid that type of work altogether, thinking it’s not that relevant to their goals. Why risk 20 x 400 meters on the track when I’m racing 50 miles? And how the heck could 6 x 1 minute fast hills (or the 10 x 30 seconds fast protocol from the Physiology Reports study) have any benefit at all if a study might show it doesn’t change the VO₂ max number?

Now you can see why it’s important to dispel the notion of the raw VO₂ max number being the goal when talking about training. First, the workouts to improve running economy don’t need to be that hard, with the aim being relaxed output that makes faster paces take less energy. We don’t want to practice going hard, since that can reinforce inefficiency and increase injury risk, all without big aerobic benefits since VO₂ max won’t change a ton anyway. Second, the plan can be shorter in duration because the adaptations we are looking for can happen rapidly off a good aerobic base.

The most fun part about applying these principles is that you can improve your speed quickly, like the participants in the Physiology Reports study but to an even greater extent. Velocity at VO₂ max is a perfect goal for a short training cycle because it targets every system at once. Aerobically, the top end output will have some benefits, particularly for athletes that have not done this type of training before. But what we’re really focused on is the musculoskeletal system, biomechanical system, and neuromuscular systems feeding back onto one another through a balanced mix of low output and high output work.

Like a late 90s star showing you the bedroom on MTV Cribs, this is where the magic happens. Those adaptations then feed back into the aerobic system growth. Easy running and tempos get faster and more efficient, which improves the aerobic system, making intervals and speed better, which makes the aerobic system even stronger. From a solid aerobic base, improving velocity at VO₂ max pushes the fitness snowball down the hill of long-term growth. I save my snow metaphors for springtime because I’m unpredictable like a feral mongoose.

That running economy improvement will distribute to better climbing and better all-day paces, raising both the floor and ceiling on race performances. You can insert this 6-week cycle anywhere in the beginning or middle of a season, just make sure you start with a good aerobic base, ideally with some faster running and strides too. And even the first 3 weeks alone would be a good stimulus for many athletes, so don’t feel obligated to do the whole thing at once.

Things to know:

- Each day is given as a range of miles, with the design being to stay at the low, middle or high end without going back and forth too much week to week. Start at the lower end of the range unless you have done higher mileage in the past.

- Be careful increasing mileage, and always rest or x-train at the first sign of injury.

- You can use run/walk strategies to do the designated mileage. And when that’s not possible, remember a five-minute run counts too.

- All of the numbers in the plan are general guidelines, rather than specific rules. Mix it up to fit your life and background.

- Do light rolling/massage and optional light stretching daily, and make sure you’re always eating enough food.

- The plan is designed for an athlete that wants to optimize their potential, but no single day is too important. Prioritize happiness and health above all else. Before starting any new routine, talk with a doctor or medical professional. This is not specific coaching advice for your individual history, but a general template to help you design your own plan. It’s always best to work one-on-one with a coach.

- You are loved and you are enough, just as you are, always. Not directly related to the plan, but an important background principle.

Terminology:

Rest days: you can be active, but no pounding on your legs. Rest day routine article

Easy runs: relaxed and effortless, but can progress to steady running when you feel good as long as it’s not every easy run.

Aerobic build week: semi-structured week with aerobic emphasis

Cross training: bike, elliptical, swim or hike ideal. Cross-training article

Hill Strides: powerfully efficient on moderate grade. Hill strides tutorial article

Flat strides: the fastest you can go without straining

Tempo runs: around 1-hour effort, relaxed and not too hard

Combo Workouts: multiple intensity-related stimuli in a single workout

CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD 6-WEEK SPEED-BUILDING PLAN

You got this!

David Roche partners with runners of all abilities through his coaching service, Some Work, All Play. With Megan Roche, M.D., he hosts the Some Work, All Play podcast on running (and other things), and they wrote a book called The Happy Runner.