4 Lessons from the Winter Olympics for Trail Runners

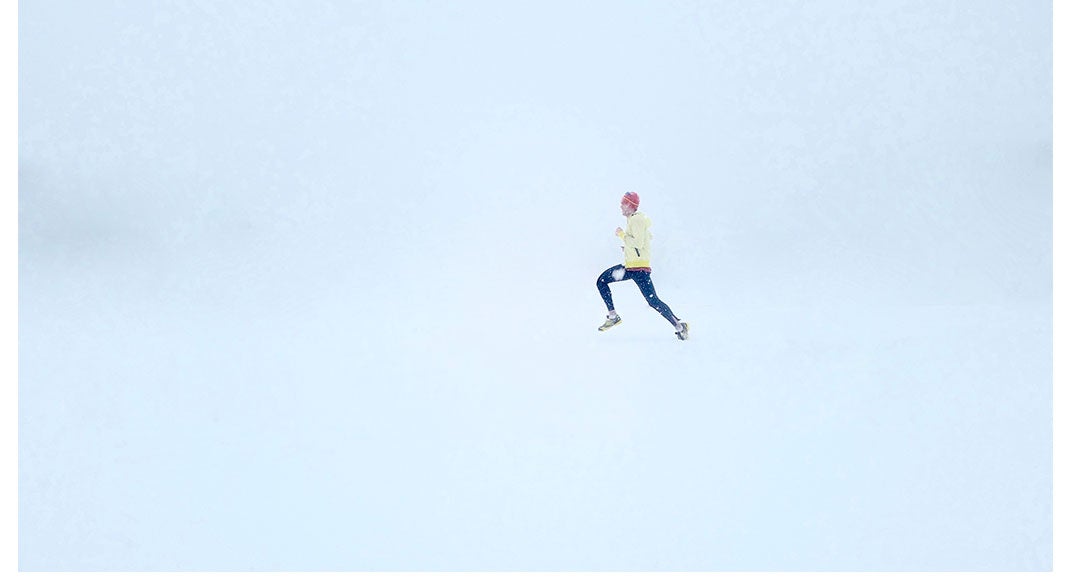

Photo courtesy of Unsplash

The Winter Olympics happen once every four years. But for the athletes, they happen every day, usually for decades.

That’s a lot to think about. You know how it can be exhausting to see a to-do list with 10 or 20 tasks? Now imagine a list with 20,000 tasks.

Almost every Olympic athlete spends most of their lives going through those tasks one-by-one, checking each box. Train five hours on Tuesday? Check. Spend another three hours studying and learning? Check. Media responsibilities and branding? Check. Train six hours on Wednesday? And on and on. They must feel a bit like Sisyphus, pushing a boulder up a never-ending hill, hoping it doesn’t roll right back down.

Any big task is like that when you really think about it, whether it’s sports or business or parenthood. The unglamorous daily grind is remarkable only in how unremarkable it is—a single brushstroke on a blank canvas. Add up lots of brushstrokes, though, and you can have a masterpiece.

Trail running is the same way, with each daily experience being what counts. There is a lot we can learn from those Olympians. How can we become better runners (and people) in the context of a long (and hard) journey? Here are 4 lessons:

Be honest

Just before entering the starting gate of the slalom, the twisty downhill ski event where she was the best in the world, Mikaela Shiffrin vomited before a disappointing (for her) run. Put yourself in her skis … what do you say?

It would be really tempting to say you ate something that didn’t sit right (which seems to be true by definition). The cushion of an excuse could make the eventual landing a bit softer. Shiffrin did not do that.

“Just nerves again,” she said, recounted by the New York Times.

She owned her nerves, and that honesty is a big part of why she is a champion. Seeing the behind-the-scenes reality for lots of trail runners through coaching has shown me that what the world sees on social media is not always the full truth. Heck, I’ve done it myself, making excuses that are only 50 percent of the story.

Honesty is essential for peak performance in any field because it’s the only way to fully understand where you are, to help you navigate where you are going. Plus, it’s good for the rest of the community to see the full picture, including the good, bad and ugly along the way.

Examples for trail runners: make sure your easy runs are truly easy; own your experiences rather than explaining them away; tell your full story, not just the highlights.

Failure is your friend

In the short program of the men’s figure-skating competition, gold-medal favorite Nathan Chen saw his dreams dashed by a fall. Put yourself in his skates … what do you do?

I’d probably lose all the confidence I had, approaching the free skate with apprehension and fear. Chen took another approach.

His free skate was historic, with a record six quadruple jumps (spinning four times in the air like a human tornado). It was the highest score of the competition.

Chen didn’t medal, but that didn’t matter. He recounted his biggest lesson to ESPN: “In the long program, I really set all my cares aside and just did what I’m good at … In the short program, I was so timid and so cautious and worried that I would make a mistake that I ended up making a bunch of mistakes.”

He viewed failure as a lesson to grow from. Based on the research about what makes us happy, it makes sense that he crushed it with a smile. In “The Happiness Project,” author Gretchen Rubin describes the “arrival fallacy,” a psychological principle that arriving at a destination is usually not what brings fulfillment. Instead, the atmosphere of growth is where happiness really happens. As Rubin writes, “The fun part doesn’t come later, now is the fun part.” Chen’s short program failure made him zoom out and realize that, letting him skate with passion in the free skate.

For trail runners, looking at growth as the place where happiness lives takes a lot of the pressure off. A failure just becomes another excuse to grow, rather than a reason to give up. Some examples: view bad races and runs as opportunities; think of injuries as creating more room for growth.

Time off can be a blessing

Nearly every Olympic athlete’s story seems to have a painful intermission—extreme injury that forced time off and a reevaluation of goals. Most winter Olympians have a list of surgeries that could be printed on a scroll. The unbreakable superhero Wolverine would probably look at the halfpipe ski competition and think, “No way, too risky, might break something.”

But another thing sticks out from those stories—usually, the athletes come back stronger. Injuries are an obvious example, though the best one from these Olympics might be a story of an unforced break. After the 2014 Olympics, ice dancers Tessa Virtue and Scott Moir took two years off to reset. As Moir recounted in 2016 to the Canada National Post: “After Sochi, we took time to do everything, step outside the skating world, and have lives—and it was wonderful.”

They came back from that break with a new fire and new perspective that let them excel to even greater heights, setting records in winning the gold medal. You see this all the time in running too, with breaks coming before breakthroughs. Part of the reason may be physical—the body can recover to come back stronger. But perhaps the most important reason is mental—the zoomed-out perspective from time off can make everything a little more fun along the way.

A lot of the time, these breaks come from catastrophe. Even those can be blessings. To paraphrase comedian Pete Holmes, by bringing up failure and injury, it’s not about ruining your morning, it’s about making your cereal taste better. Time off has a magical way of letting all of your systems switch back on when you return.

Examples for trail runners: take a few days off whenever you feel a slight injury or slightly burned out, letting your body reset when you need it.

You are capable of more than you might think

In the women’s Super-G alpine-skiing event, NBC cut away from the coverage, crowning the winner and saying the remainder of the athletes had no shot. There was one complication—Ester Ledecká.

Ledecká, primarily known as a snowboarder, shocked the world by going from never finishing higher than 19th at a World Cup race to winning the Olympic gold. When she crossed the finish line and saw what happened, her reaction mirrored the rest of the world: “How did that happen?”

So how the heck did that happen? Well, it’s the same fairytale story you see in sports all the time, whether it’s the Olympics or college basketball or trail running. She worked hard and she raced without fear, thinking not of her limits or of the results, but of her process along the way.

Trail runners can do the same thing. Self-belief doesn’t mean thinking that you’ll win a gold medal; it means knowing you can keep growing, even when handed evidence that points to the contrary. Belief might make each interval a 10th of a second faster by relaxing you and improving your running economy. Those marginal gains are nothing in a day, but in a year they can be everything.

Examples for trail runners: practice positive reinforcement with your running; view yourself in a way that removes self-judgment.

There are a thousand more lessons that winter Olympians could teach us. Cross-country-ski gold medalist Jesse Diggins alone could be the source of hundreds, from the importance of community to the power of enthusiasm to the true secret: working your butt off for many years. The over-arching theme is what counts: big dreams require little actions over a long time, so think about your running in a way that supports the daily process along the way.

David Roche runs for HOKA One One and NATHAN, and works with runners of all abilities through his coaching service, Some Work, All Play.