Coping with Ankle Sprains

How to prevent and treat ankle sprains

Illustration by Steve Graepel

You’re cruising along a beautiful singletrack, enjoying your elevated heart rate and a great view, when suddenly you lose your footing. Ouch! Along most trail runners’ favorite routes lie such potentially ankle-turning hazards as roots, rocks and quick descents. A brief moment of not paying attention to where you’re stepping is all it takes to disrupt the ankle’s delicate balance. Even worse, injured ankles remain weakened for an average of six months.

Up to 80 percent of all ankle sprains stem from previous injuries. Athletes who have an injury-weakened ankle joint are about 10 times as likely to suffer a repeat injury than those who don’t. Twelve to 20 percent of all sports injuries are ankle sprains.

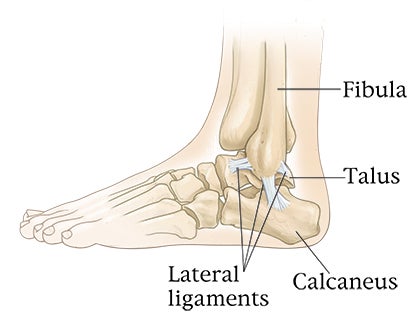

The ankle’s physiology is one reason why inversion injuries are so common. The inside of the ankle is much more stable than the outside, especially when the toe is pointed (plantar flexed). The good news is that you can quickly and easily determine if your ankles are weak, and take precautions to keep them healthy.

ARE YOU AT RISK?

According to head athletic trainer at Boston College, Bert Lenz, “The most common type of ankle sprain seen in sport involves the ligaments on the lateral [outside] aspect of the ankle. Injury to these ligaments most often occurs with a ‘rolling’ of the ankle inwards, or an inversion mechanism, such as simply stepping on a rock while running. This type of inversion action to the ankle can damage one or all three of these ligaments in differing degrees.”

Sports medicine professionals define dysfunction resulting from ankle inversion injuries as a reduction in proprioception, or knowing where your ankle is in space and what it is doing. If your brain isn’t aware of how your ankle should react, you’re much more likely to trip over a log or roll your ankle in a downhill divot. So how do you know if you have a weak or “dysfunctional” ankle? According to a study published by T. H. Trojan and D. B. McKeag in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, the simple “single-leg balance test” is a reliable way to predict the possibility of future ankle sprains.

To perform the single-leg balance test, stand barefoot on a flat surface. Balance on one foot with the opposite leg bent and not touching the weight-bearing leg. Focus the eyes on a target, then close them for 10 seconds. If you sense any imbalance, the test is failed. If the foot moves on the floor, the arms move, the legs touch or a foot touches down the test is failed. A failed test suggests the individual is more susceptible to ankle sprains and injuries. Further, according to Trojan and McKeag, athletes who failed the single-leg balance test but taped their ankles were less likely to sustain ankle sprains than those who didn’t.

AN OUNCE (OR TWO) OF PREVENTION

So here’s the damage control. If you have a weak or dysfunctional ankle, you can reduce the likelihood of injury, and re-injury, by taping, bracing, stretching and strengthening the joint in question. If you’re planning on taping your ankles, see a physical therapist or an athletic trainer who can show you how. Ankle braces are easily found in your local drug store and can effectively fortify vulnerable joints.

Another ankle-saving consideration involves selecting the proper shoes. Jason McGrath, USATF Level 2 Track Coach, decorated ultrarunner and shoe expert, suggests trail-specific shoes that are neutral and low to the ground. Most running shoes suitable for pavement are well cushioned; however, a thick midsole means that your feet are farther from the ground, causing less stability and increasing the probability of rolling an ankle. McGrath also warns against wearing “stability” shoes, common on the road-shoe market. These shoes contain medial posting, or a separate material lining the instep that prevents overpronation of the foot. When running on uneven terrain these shoes place more stress on the physiologically weaker lateral (outside) portion of the ankle, making it more likely to roll. In the meantime, you will also want to add ankle strength and flexibility exercises to your workout regimen.

RECOVERY ROAD

In the event that you do sprain your ankle on the trail, here are a few tips to get yourself back in action fast. Everyone’s doctor suggests RICE immediately following an ankle injury. RICE stands for Rest, Ice, Compression and Elevation and is the old standby for athletic injuries.

In the article “Management of Ankle Sprains,” authors Michael W. Wolfe M.D., Tim L. Uhl PhD., ATC, Carl G. Mattacola PhD., ATC, and Leland C. McKluskey M.D. emphasize the importance of stretching and exercises to maintain range of motion during the initial icing stage immediately after injury. Compression using an elastic bandage alleviates swelling in the area.

According to a study by Bleakley, McDonough and MacAuley in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, the best way to ice an ankle sprain is in 10-minute intervals, alternating with gentle stretches. This procedure may be repeated every two hours, and was shown to significantly reduce the pain felt on activity within the first week of injury. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) also alleviate swelling and pain. After pain and swelling are gone, begin a stretching and strengthening routine, taking care to tape or brace your ankle before hitting the trails.

RICE 101

REST: Stop running immediately after ankle injury occurs.

ICE: Apply ice for 10 minutes, stretch for 10 minutes, re-apply ice for 10 minutes and repeat every two hours until swelling subsides.

COMPRESS: Cut a U-shape out of a wad of gauze. Place the bottom of the U underneath the bone on the outside of your ankle (“ankle bone,” or malleus) so that the bone is surrounded on both sides and underneath by gauze. Hold this in place and wrap an elastic bandage toe to mid calf around the ankle. Otherwise use an ankle brace.

ELEVATE: Lie or sit down, relax and place the injured ankle no lower than six inches above the heart until swelling subsides.

This article originally appeared in our March 2007 issue.