Inclination for Speed

Run uphill like the pros

To capture last year’s U.S. Mountain Running Championship title at Mount Washington, Eric Blake ran the equivalent …

Illustration by Kevin Howdeshell

To capture the 2008 U.S. Mountain Running Championship title at Mount Washington, Eric Blake ran the equivalent of almost four Empire State buildings (4650 feet) in 60 minutes—that’s 7:59 minutes per mile. To place fifth at the World Long Distance Mountain Running Championship, Galen Burrell climbed 6000 feet in the Swiss Alps at an 8:47 minute-per-mile pace for the marathon’s last half.

How do top trail runners ascend steep, gnarly grades for hours without exhausting and injuring themselves? Though it helps to train for years and have heaps of talent, proper technique and a smart strategy dramatically increase your speed on steep inclines.

Posture Is Paramount

“Let gravity help you by leaning into the hill, and use short steps with a quick tempo,” says mountain-running pioneer Chuck Smead, 56, of Mosca, Colorado. Smead’s technique makes it no wonder he’s won every major U.S. mountain race and still accumulates division victories.

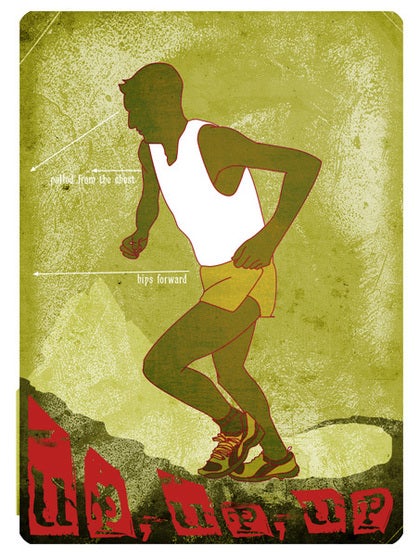

Maintaining speed on long climbs requires an efficient stride, which means keeping your hips and midsection ahead of your feet, so you “fall” up the hill. Use the stance of a ski jumper: bend forward from the ankles with your shoulders, back, and bum in a straight line. Avoid bending at the waist, which strains your back and throws your weight backward. Rather, imagine a bungee cord attached to your chest, pulling you forward with your body properly aligned.

Short and Quick

Aim for a cadence of three steps per second, no matter the grade, by using short, quick steps. The steeper the incline, the smaller the steps. “A shorter stride will keep you leaning forward,” explains Professor Reed Farber, biomechanics expert and director of the Running Injury Clinic at the University of Calgary. “If you can see your toes in front of you, you’re over-striding and losing efficiency.” On technical terrain a fast tempo also provides more agility to dodge obstacles.

Ball First, Heel Second

Good mountain runners land on the ball of the foot, then lightly touch down on the heel. “This mid-foot strike spring loads your Achilles tendon to propel you up the hill and keeps your weight in front,” explains Dr. Ferber. Heel striking, on the other hand, applies a strong braking force that throws your weight back.

But landing exclusively on your toes can cause ankle pain and calf strains. “Many runners tend to stay on their toes for steep climbing,” says Burrell, who recommends this technique only when sprinting up short, extreme grades. “On long uphill grinds, this will burn out your calves, so stretch them out by using the whole foot.”

Armed Forces

Swinging your arms encourages quick leg turnover and provides a boost on nasty grades. “The arms don’t contribute much to forward motion on the flats,” says Professor Bryan C. Heiderscheit, director of the Neuromuscular Biomechanics Laboratory at the University of Wisconsin. “But on steep hills, they provide vertical [uphill] propulsion as well as forward force.”

Race Mode

In uphill races, Burrell says, “Abandon expectations for a certain per-mile pace and focus on breathing, form and effort.” Think of an Italian sports car in the Swiss Alps, and shift down to a low gear for a pace you can sustain.

“If you go too hard, you’ll fade,” says three-time World Masters Mountain Running Champion, Simon Gutierrez. “Use a heart-rate monitor to learn where your lactic acid threshold [exercise intensity at which lactate accumulates in the muscles, causing fatigue] is and then stay just under that point.” Or gauge your effort by determining the maximum number of breaths-per-stride you can maintain for more than 30 minutes, and make this your race pace.

For extreme grades where form and efficiency decline, switch to a power hike or a “sideways” stride (see below).

At a hill’s crest, accelerate up and over to carry the momentum on the downhill. And at the descent’s end, use your downhill speed to accelerate the first part of the next hill. Ultramarathon legends Kami Semick and Scott Jurek use this “transitioning” strategy to shave minutes off their race times.

Training Mode

Ironically, the treadmill is many elite mountain runners’ tool of choice for uphill training. It allows them to skip damaging downhills and train through icy winters. Start with 20 minutes a week at 10- to 15-percent grade. Add five to 10 minutes weekly, and, if you’re up to it, work up to Gutierrez’s non-stop 65 minutes at 15-percent grade.

Once a week, run up a 2000-foot climb just below your lactic-acid threshold to build efficiency and confidence. If you have no mountains nearby, run the stairs of a high-rise. Zac Freudenburg, who placed eighth last year at the World Long Distance Mountain Running Championship, trains in a 45-story building in his hometown of St. Louis, Missouri.

“Use lunges, squats and box jumps to strengthen the exterior hip muscles (gluteus maximus and hamstrings), which provide about 75 percent of your vertical power on hills,” says Dr. Heiderscheit, who says the calf muscles produce horizontal thrust and support the mid-foot landing, adding, “If you aren’t accustomed to landing on your toes, do calf raises for four to eight weeks to build the requisite strength.”

Tough Climbs

Danny Dreyer, author of Chi Running and a renowned coach who integrates tai-chi principles into trail running, recommends turning your hips to the side to take the workload off your quads and hamstrings, and better engage your core muscles when going up steep inclines to avoid exhausting your legs.

Diagonal Feet. Facing uphill with your feet pointing at 12-o’clock, turn only your feet to 10-o’clock. Keep your feet at this angle as you run, slightly crossing your feet in front of each other.

Arm power. “The key is to engage your side (oblique) stomach muscles, by accentuating the motion of the downhill arm,” says Dreyer. “Swing the arm strongly across your body and up to your chin, just like an upper cut.”

Change Sides. After about six to 10 steps, switch sides by moving your feet to a two-o’clock position.