The Puzzlemaster: How Courtney Dauwalter's curiosity and problem-solving push her to the brink of what's possible in ultrarunning.

Sixty miles into her first 100-mile attempt, Courtney Dauwalter was done.It was 2012 at the Run Rabbit Run 100 in Steamboat Springs, Colorado. She was 27 years old and determined to find out what her body was capable of. Not as much as she had hoped, it seemed. Her legs were shot, her stomach ached and she was exhausted.

“I doubted myself, maybe I wasn’t capable of running 100 miles,” says Dauwalter, “that feeling of doubt, it took over”.Dauwalter DNF’d there, just past the halfway point. Instead of defeat, curiosity overtook Dauwalter.

“There were two paths I could take,” she says. “I could accept that 100 miles isn’t for me, or I could figure out how to make it happen.”

Just over seven years later, she has finished over a dozen races of 100 miles or more and has DNF’d just two. Now, she’s one of the most dominant runners in the sport, famous for her capacity to leave competitors—both men and women—in the dust.

Teacher Becomes The Student

Seemingly overnight, Dauwalter went from a middle-school science teacher to one of trail running’s most dominant athletes. She’s ticked off notable wins across ultrarunning’s most prestigious, and some lesser-known events. She’s known as the woman who can outrun men at extreme 200-mile distances.

She has the top-end speed to win events like the Western States 100-mile race and the endurance to set course records at the Tahoe 200-miler. She has the turnover and stamina to set course records at the Javelina Jundred 100K, compete in 24-hour track events and win big-mountain events like UTMB. She has formerly held the American women’s record for most miles run in 24 hours, 159.3 miles in 2017. She doesn’t specialize in a particular surface or distance. She specializes in the unique, problem-solving mindset that ultramarathons require.

Dauwalter is lanky and tan, proof of a lot of time spent running outside her home in Golden, Colorado. Her blonde hair is perpetually pulled back in a ponytail, and sometimes folded over in a small, straw-colored bun. Her wide blue eyes fold into a squint when she laughs, which she does often. Her smile is relaxed and her teeth are shockingly white (Dauwalter is known to brush her teeth several times throughout the course of 100-mile-andup events).

“She seems to be mostly driven and motivated to find out what her limits are, not necessarily just to win,” says Addie Bracy, a professional ultrarunner and sport-psychology consultant. “ In pursuit of that mission she has developed some ability to just not let pain and discomfort bother her. If something is going wrong or something is hurting, she treats it as a fixable problem.”

From Minnesota To The Mountains

Dauwalter, now 34, grew up cross-country skiing in Hopkins, Minnesota, a suburb just west of Minneapolis. She ran to stay in shape for ski season and competed in cross country. She went on to ski for the University of Denver, where she studied biology to become a science teacher.

After graduating, in 2007, teaching took her to Mississippi. A lack of snow cleared the way for Dauwalter to pursue running year-round.She signed up for a couple of marathons, which she says she “survived.” That led her to her first trail race, a 50K in Texas. Dauwalter won.

“It was an amazing day, just weaving through the woods. The community was so welcoming and chill,” she says. “It felt like this grand adventure where we were all just trying to survive.”

She was hooked. That 50K led to a 50-miler a few months later, and her first attempt at a hundo a year after that. When she DNF’d at Run Rabbit Run in 2012, she was already registered for her next 100-mile race, the Superior Fall Trail race in Lutsen, Minnesota, just about a year later.

She spent the next year training and teaching in Denver, where she met her husband Kevin Schmidt, a runner and software engineer.

Some mutual friends had introduced them, referring to Dauwalter as a gal who “liked to run a bit.” Naively, Schmidt suggested they tackle a couple of Colorado’s Fourteeners for a first date.

“It took everything I had to keep up with her, but somehow I survived!” says Schmidt. “I’ve been trying my best to keep up with her ever since.”

“She seems to be mostly driven and motivated to find out what her limits are, not necessarily just to win,”

—Addie Bracy

Picking Up The Pieces

Dauwalter approaches training like a problem to be solved. Her attitude towards her RRR DNF was reminiscent of Thomas Edison’s assertion that he had never failed, but had succeeded in finding 10,000 ways to not make a lightbulb. In training, Dauwalter began to tick off ways to not make a lightbulb.

Her stomach had been a problem in her first 100, so she experimented with different fuels to figure out what worked.She built up distance more gradually and tested different configurations of gear. Before her DNF, she had been watching what other runners were doing and attempted to emulate their strategies.

Once, running a 50, Dauwalter implemented advice she’d been given about the efficacy of 5 Hour Energy. Ten miles in, she tossed one back and won. The next time she tried it, she ended up puking for hours.

“There’s a million theories out there,” says Dauwalter. “You really just have to test stuff yourself to see what works.”

When she started to approach training as a personal puzzle, things started to click into place. Food was nutritional Tetris, and Dauwalter was figuring out the exact configuration of carbs that would allow her to push her limits.

“There was a lot less barfing after that,” says Dauwalter. “I dialed it in, and started relying on Honey Stingers, Tailwind and mashed potatoes.”

As she stood on the start line of the Superior Falls Trail 100, Dauwalter told herself that she would finish, no matter what.

“I didn’t care what it looked like, or what place I was in, but I was going to get to the finish line of that race,” says Dauwalter.

And finish she did—in second place and in the top 10 overall.

The emotion of completing a goal that meant so much to her was overwhelming. “I cried for the last 10 miles of that race,” remembers Dauwalter.

It sparked a nascent curiosity in her to see what she was capable of, and how much farther, and faster her legs could carry her.

In 2017, Dauwalter stepped out of the classroom to pursue running full-time.

“Mostly, I just wanted to find out what was possible, for me and for the sport,” says Dauwalter. “I didn’t want to look back in 50 years and wonder what could have happened if I had invested more in this sport.”

RELATED: Beating The Boys

So, Dauwalter went all in.

Fluid And Freestyle Training

Dauwalter’s problem-solving approach to training stops just past being methodical, but far short of being obsessive.

She does not have a coach. Her training plan is fluid and freestyle. Mostly, she runs a lot. Lately, she’s been averaging about 100 miles a week while mixing in some cross-country skiing and stationary biking. She’s shifted her focus away from hammering out miles to include more strength work and bodyweight exercises. She likes to split up her days by tackling the majority of her mileage and gym time in the mornings, then joining her husband, Kevin, for a few more miles when he’s finished with work.

Her affinity for candy as fuel is well documented, and she loves anything fruity or gummy, though she does try to eat it seasonally. In the fall, she opts for candy corn, and conversation hearts in spring.

At Big’s Backyard Ultra, a race that pits competitors against a 4.166667 mile loop for as many hours as they can continue to tick off laps in under an hour, she refined her nutritional strategy. Dauwalter chowed down on Honey Stinger Waffles, cheese quesadillas, pierogies and pancakes before switching to McDonald’s double cheeseburgers for the final, grueling hours.

Her laid-back approach to training and fueling is echoed by her choice of apparel on the trail. Dauwalter eschews the form-fitting spandex favored by many trail geeks and opts instead for looser T-shirts and knee-length shorts, which the internet has dubbed “Shortneys.”

John Stanley is a frequent running buddy, who befriended Dauwalter while they were both teaching and coaching cross-country in Denver.

“On most of our runs together I feel like I’m training hard and she is doing a recovery run. But running with Courtney, whether we are doing long easy miles or more intense training, is always great,” says Stanley. “It is just getting out and sharing miles with a friend. Even though she can drop me at any time, she is willing to stay with me and give me encouragement.”

On the occasion that Dauwalter does drop him on a hill, she’ll always come back down and throw in an extra repeat, just for the company, says Stanley.

It’s this balance of problem solving without overthinking that has allowed Dauwalter to excel at long distances over the past few years.

In 2017, Dauwalter won the Moab 240-mile race, which traverses the high desert in Moab, Utah, outright, beating the second-place competitor by 10 hours. Wins at the 2018 Western States Endurance Run and the Tahoe 200 (where she finished second overall) solidified her as an ultra-icon. Still curious, Dauwalter kept pushing.

In 2018, she was runner-up at Big’s Backyard Ultra, an almost sadistically challenging race where runners must complete a 4.16667-mile loop each hour for as many hours as possible. If you want to relax and regroup, you earn that time by running faster. The last runner standing wins. On the third day of the race, after 279.2 miles and 67 laps, Dauwalter conceded the race to Johan Steene from Sweden. She and Steene had run 33 miles farther in the race than any previous competitor in the race’s eight-year history.

For someone in Bracy’s field, Dauwalter might be the closest thing to a perfect mental specimen, a petri dish of almost unshakeable mental toughness.

The Mental Game

Though these major victories brought Dauwalter into the spotlight, she’s a very private person and uncomfortable talking about herself.

“I remember when we would see each other on a Monday morning after she had raced over the weekend and I would ask her how things went. Her response was always something like, ‘OK. What did you get up to this weekend?’” says Stanley. “Through further interrogation, I would find out she won the race and broke a course record.”

There’ve been several attempts to plumb the depths of Dauwalter’s intensity in racing. One of the better known is an appearance on Joe Rogan’s podcast. Rogan interrogates Dauwalter, asking her what her secret is. Demons? Jedi-mind-tricks? A yet undiscovered form of meditation? What’s her secret?

“Just … not letting myself not have an excuse to stop,” replied Dauwalter.

“That’s terrifying to everybody else … Maybe there’s nothing more to it,” responded Rogan. “Maybe it’s just incredibly hard work and grit. That could be just it.”

“It could be really simple,” said Dauwalter.

Is it?

Dauwalter is a zen koan in action. A master of mindfulness who doesn’t need meditation. Her grip on things is so relaxed that she’s able to elicit complete control when it counts. The sound of one hand clapping.

Her approach is scarily simple. Find the dark moments, and embrace them.

“Your best bet is to barrel forward. I like going into those dark moments and learning from them,” says Dauwalter. “You don’t get to summon those whenever you want. You’re doing something really difficult, and that’s how you grow your capacity to endure.”

“While she probably does have some physiological attributes that help with her success, I still think it’s her psychological advantage that has set her apart,” says Bracy, who has interviewed Dauwalter multiple times in her studies as a sports psychologist. For someone in Bracy’s field, Dauwalter might be the closest thing to a perfect mental specimen, a petri dish of almost unshakeable mental toughness.

It’s not all mind games. Dauwalter is also known for high-volume training weeks with massive amounts of gain. Combine her mysteriously un-structured training with the black box of her brain, and you get a trail-running supermachine.

“Court is the toughest and hardest working person I know,” says Schmidt. “She’s also the most humble and kind person I know. Despite her many accolades, she seems to ground herself in knowing she can always improve and never lets success go to her head.”

Fellow runners recognize Dauwalter for her positivity while racing.

“She is just a very positive, happy and kind person and I can say from racing alongside her that she is still that way in the middle of a 50-miler,” says Bracy.

Bracy remembers encountering Dauwalter 30 miles into a 50-mile race, the longest Bracy had ever run at that point. When Bracy confided in her competitor that her legs felt like crap and she was nervous about the direction her race was headed, Dauwalter responded rationally, and with compassion.

“That’s awesome! It’s OK that your legs hurt, that’s normal. You’ve totally got this!” said Dauwalter.

“That just showed me how she treats the pain and discomfort of racing long distances,” says Bracy. “In the most basic context, I think Courtney has developed the mental strength necessary to get a near maximal effort out of her body.”

In Running As In Life, What Goes Up Must Come Down

2019 was a year of ups and downs.

Dauwalter had her sights set on some of America’s premiere races. But, the weather had other plans. The Hardrock 100 was canceled due to historically high snowfall and treacherous avalanche debris in Colorado’s San Juans.

Later in June, Dauwalter lined up at the Western States Endurance Run to defend her title. Around mile 60 an unsolvable problem popped up—Dauwalter’s hip began to send shooting pains into her leg. Dauwalter limped into the Green Gate aid station at mile 78.9. She had two choices; she could try to walk it in, or take her second-ever DNF. Deciding she didn’t want to aggravate her injury further, Dauwalter dropped from the race.

Injured, and without Hardrock on the horizon, Dauwalter doubled down on healing. She rode her bike. She rehabbed her hip by refocusing on strength and flexibility training. Sometimes, even pros need a reminder to foam roll every once and awhile.

“It was a weird summer,” says Dauwalter. She wasn’t used to putting in so many miles on a road bike, as opposed to the trails that she loved. As she started to string together longer and longer runs, another goal started to feel possible.

RELATED: How Courtney Dauwalter Won The Moab 240 Outright

Throughout her turbulent summer, UTMB loomed large. While many runners flock to Mont Blanc’s shadow to spend most of the summer examining the TMB trail’s many peculiarities, Dauwalter stayed at home in Golden, Colorado, to focus on rehabbing her hip.

On race day, Friday, September 30th of 2019, says Dauwalter, “Since I’m not a calculated person, I thought if I just kept going around the mountain, I’d find my way back to Chamonix eventually.”

Dauwalter took the lead around the halfway point, at the Bonatti aid station, and held it as the race circumnavigated the Mont Blanc Massif, crossing from Italy into Switzerland and back into Chamonix, France.

The last miles, however, were excruciating for Dauwalter, who spent the last couple of hours visibly hobbling (albeit quite quickly) over the Alps’ challenging, steep, rocky terrain. Her gait was forced and off kilter, her face set in an expression of obvious effort. After 24 hours, 34 minutes and 26 seconds, she beat the next woman, Sweden’s Kristin Berglund, by over an hour.

While Dauwalter had won large international races before, like Madeira Island Ultra Trail, Tarawera 100K and Ultra Trail Mount Fuji, UTMB was a recognition of her dominance in the sport. Dauwalter was out to satisfy her own curiosity of what she was capable of—and become one of the world’s best trail runners in the process.

After some time off at the end of 2019, Dauwalter has been focusing on base building and cross-training to prepare for 2020.

“I’m feeling good and excited to get the race season going!” says Dauwalter.

Instead of a set-in-stone ticklist, Dauwalter has a “wish-list” for the year to allow for some flexibility. This year, she hopes to get back to UTMB and Big’s Backyard Ultra, as well as tackling the Hardrock 100.

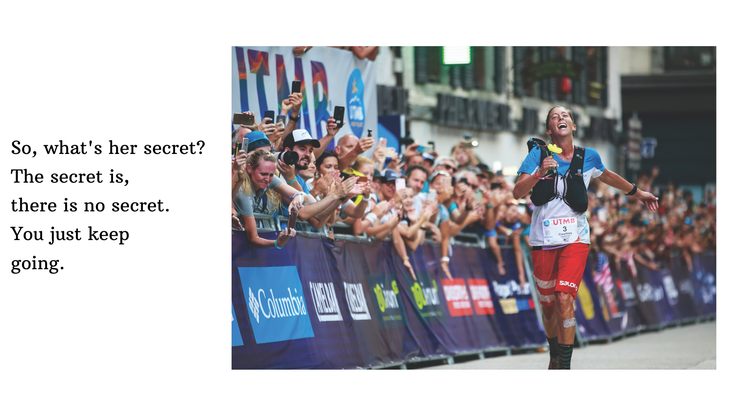

So, what’s her secret?

The secret is, there is no secret. You just keep going.

Zoë Rom is Trail Runner’s Editor-in-Chief and the producer of the DNF podcast. She enjoys long runs in the mountains and making pizza at altitude.