Ultrarunning Back in the Day

Q&A with Ultrarunning Pioneer and Coaching Legend Jim O’Brien

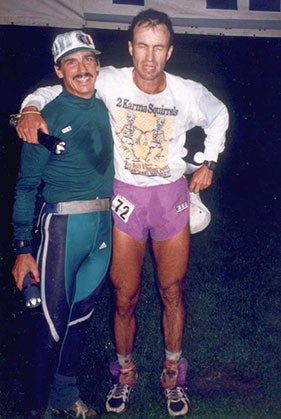

Jim O’Brien and a knackered Larry Gassan at the 1996 Angeles Crest 100-miler. O’Brien paced Gassan the last 25 miles. Photo courtesy of Larry Gassan

(This article first appeared in Ultrarunning in 2003.)

Jim O’Brien, coach, ultra legend and unrivaled Angeles Crest 100-mile record holder announced his retirement from private coaching September 1, 2003. O’Brien cited professional and familial reasons for disbanding his Team Blarney, which was synonymous with running achievement here in Southern California. There wasn’t enough time in the day. In addition, Jim’s daughter, Erin, is now 10, and time is always short.

Professionally, while coaching track at SoCal’s Arcadia High School with 85 runners, he also coaches at Pasadena City College, where he’s coaching track and cross country and teaching PE classes.

At Team Blarney, Jim coached a spectrum of runners and distances at his memorable Monday (and then Tuesday)-night workouts. The distances spanned red-hot 10Ks through the 100-milers, and included runners from their late teens into mid-60s.

Jim brought a high level of ethics and honesty to his craft. That alone would make him a standout. But his athletic accomplishments backed it up, big time. His 17:35:48 Angeles Crest 100 record of 1989 is the benchmark that all of us have measured ourselves against. And that was when the course was almost two full miles longer than it is now.

At Leadville in 1989, his epic surges up Hope Pass on the way to Winfield completely buried four-time winner Skip Hamilton. Then on the way back it was rain and mud to a course record that stood for five years until Juan Herrera took it in 1994 … on a clear and calm night.

To flesh out some of these details, I caught up with O’Brien on a recent Tuesday night at Pasadena City College.

Q&A with Jim O’Brien

How did you get into ultrarunning?

I was in San Diego in the late 70s-early ’80s, going to school at San Diego State University getting my BS in PE. At that time I was road racing. I’d heard about a Run Across America. Unlike a stage race, it was first to the finish. It got me thinking, so there was a year’s leeway to prepare for the event. However it later got cancelled due to sponsorship problems.

In ’85 I’d moved up from San Diego to Monrovia and got a job at Cal Tech in Pasadena teaching PE. Tried the Mount Wilson Trail Race, an eight-mile uphill grinder from Sierra Madre up the Old Mount Wilson trail to the observatory. I won my age division.

I met local ultrarunners like Jack Slater, Ralph West and Judy Milke. At this point I had run 13 marathons in a year, mainly to demystify the marathon process. I raced two and ran 11 as training runs. I’d also heard about Ken Hamada’s idea of putting on a 100. 1986 was the inaugural Angeles Crest 100. I set my sights on ’87, and tried to get in but Hamada wouldn’t let me in—no 50-milers under my belt, and only a string of sub 2:30 marathons.

So for my first 50, I did the Mile Square 50 in Fountain Valley, which was 10 loops. I set a goal of 33 to 35 minutes per loop, for a sub-six-hour finish. By 26 miles I had lapped everybody, and won it in 5:58. The steady pace was the key to a good performance.

So, what happened at AC100 in 1987?

I ran it with bronchitis and finished third in 19:51 behind Jim Gensichen, with Jim Pellon seven minutes in front of me. Afterwards I took to bed with pneumonia. What I learned was that solid food in a race is inefficient, but I had done it out of deference to common knowledge. I started to really research liquid nutrition.

How did you get ready for the 1989 AC100?

I really prepared for Angeles Crest that year. I sacrificed for six months before the race. Meticulous planning. I had a crew, pacers and my nutrition dialed in. I had three plans. Plan C was to run the record. Plan B was to run conservative, and break the existing record. The secret Plan A was to go under 18 hours. The training began a year before the race.

My mileage for the six peak weeks before the race, nine weeks prior to race day, was 150 to 200 miles per week in a continuous build. Then I tapered downward 200-100-75-50 per week. The Tuesday before the race I did a speed workout to deplete the fast-twitch muscle fibers.

I got back to basics on what worked. Nutrition was going to be liquid based, in total defiance of conventional wisdom. I was using mango nectar mixed with Carboplex, with ProOptimizer as the protein supplement every 25 miles, and water with potassium tablets for electrolyte absorption.

How did the race shake out?

After a cool start, the day was warm through Shortcut [mile 59]. I was outracing most of the aid stations, which had not set up yet. For instance, I beat the crews up to Newcomb’s Pass [mile 68]—the trucks passed me on the way up the road.

After Newcombs, a heavy inversion layer cut visibility down to three feet in through Santa Anita Cyn to Chantry [mile 75]. However, I knew the way cold. At this time I was running a caloric deficit because my bottles were mixed and still on the trucks, and my pacer Bill Kissell couldn’t get to them without me waiting around.

At Chantry there was no scale to weigh in on. I stuck to my plan throughout. I stayed in the chair for the full 10 minutes getting a massage etc before heading up Mount Wilson.

How about Leadville the following year?

My original goal was to do every hundred that existed in 1989. These were Old Dominion, Vermont, Western, Leadville, Wasatch and Angeles Crest.

At Leadville I did the homework for six weeks before the race, splitting my time between Steamboat Springs (three days) and Leadville (four days) each week.

Come race day I ran alongside Skip Hamilton, a four-time winner of the race, known as “Mayor of Leadville,” which was OK by me. Skip held back in the first 13 miles. When I was changing out of my tights at May Queen, he passed me. I let him lead until the base of Mount Hope, which was about a fat mile past the water crossing after the elk wallow at Twin Lakes. I passed him there.

I started throwing surges at Hamilton going up to Hope Pass. I’d let him come close, then surge ahead. Then I’d repeat. By the top of Hope I was pretty whacked. Bill Clements passed me here, and I let him go.

I saw Skip on his way up to Winfield while I was heading back to the base of Hope Pass—he wasn’t long for the race (and dropped at Twin Lakes). The return leg to Twin Lakes took 2:30 as planned.

I took the lead back from Bill at Twin Lakes. Midway between Twin Lakes and Half Moon, it began to dump rain. The trails turned to grease. I dropped my first pacer who was suffering from intestinal distress, and ran solo to Fish Hatchery [mile 75]. I picked up a wild-card pacer, who probably had a snappier workout than he bargained for, slipping and sliding up Pole Line Pass—complete with lightning and hail.

Out of May Queen [mile 87] the mud was so bad that a USFS truck sank to its hubs on the dirt road while trying to light the way.

O’Brien crossed the finish line in a record time of 17:55. There had been three inches of hail on the streets of Leadville at the finish line. His record stood until 1994 when it was broken under a mild full-moon dry night by the Tarahumara runner Juan Herrera wearing huaraches.

The following year, before running Wasatch, O’Brien was convinced that a record was possible. Once again, he did the homework. He stayed in Park City for three weeks, and trained with Dana “Blood and Guts” Miller. Their families socialized together and made the business of training more pleasant. Finally, he ran the course in three sections over three days.

Race day was notable for the pouring rain that greeted the runners at the top of Francis Peak, and that Miller had completed half of his Double Wasatch along with Dennis Herr.

The race threw a succession of obstacles at O’Brien. The course itself is difficult on a good day. Fog and rain made routefinding up Chin Scraper very difficult, where he topped out on a rock crag. Rain-battered, he decided going up was safer than down-climbing. Continued rain throughout the day turned trails into mud-runs and bottomless shoe-sucking misery. Dense fog at night added to route-finding challenges up past Desolation Lake [mile 70]. O’Brien left Brighton [mile 75] just ahead of RD John Grobben, who was seriously considering stopping the race due to the extreme wet conditions. Houses were sliding off hillsides at this point. I can only imagine what the steep climb up to Ant Knolls must have looked and felt like after 18 hours of soaking rain!

Jim won it in 22:50—not a course record but almost two hours ahead of second place Neal Beidleman. There were 55 finishers out of 105 starters.

What stopped your ultra career?

A knee injury that initially was a result of a fall in 1995 while running, where I fractured the head of the femur, cracked the bone inward, which took a year and a half to heal. All other knee issues are directly related to this fall. Three years ago I had a cartilage replacement on the left knee, using my own tissue grown in a lab in Boston, which seems to have helped.

Best memories of your own ultrarunning career?

1989 Angeles Crest. The day was magic. Everything came together.

How did you get into coaching?

I was approached by the Foothill Flyers to coach them. I decided that I’d rather have my own club rather than provide “friendly coaching” and then have someone get injured, and then get sued. This way I could get USATF coverage etc.

And this led to Team Blarney, which met on Monday, then Tuesday nights at 7 p.m. for the famous track workouts.

Here is a very short list of some of the runners:

Jennifer Johnston was getting her PhD at Cal Tech, and wandered in O’Brien’s office one day in 1994. She went from being a good marathoner to winning Angeles Crest for the women twice, and was on the USA 100K team.

Bruce Hoff and Dana Taylor came in good, and came out better. Taylor came from road marathons and triathlons—set a course record at Kettle Moraine 100 in 1997, which stood for two years. Hoff began to realize some of his epic goals at places as varied as Wasatch, Hardrock, Jed Smith and Vancouver after training with O’Brien.

Joe Franko finished in the low 22s at Angeles Crest in 1990 and 1991.

Francisco Fabian, while working a six-day week as a baker and going to school, started from zero. He’d originally started jogging in a pair of Costco cheapies to quit a three-pack-a-day smoking habit. After a year with O’Brien, he finished his first AC100 in 1999, in 26:28. He then buttoned it up to a 23:55 in 2001.

Hal Chiasson, who fooled all of us with his Clark Kent CPA exterior, was in reality a tough guy waiting to happen. He did his first 100 at 55 with a 28-hour finish. Admittedly never fast but always cheerful, polite—and tough.

Chip Parsons, Nancy Tinker and many of us would await the monthly handouts of the new schedules and wonder how many spare minutes would be left in our lives. This led to some highly charged speculation on the part of some spouses who felt they were in some way ignored, but it all got worked out somehow.

What are some of the biggest mistakes beginning ultrarunners make?

Not taking the distances seriously. Not treating the training seriously. Being self-coached with no serious direction. A blind willingness to replicate mistakes. Resistance to positive ideas.