New perk! Get after it with local recommendations just for you. Discover nearby events, routes out your door, and hidden gems when you sign up for the Local Running Drop.

Photos by Luis Escobar

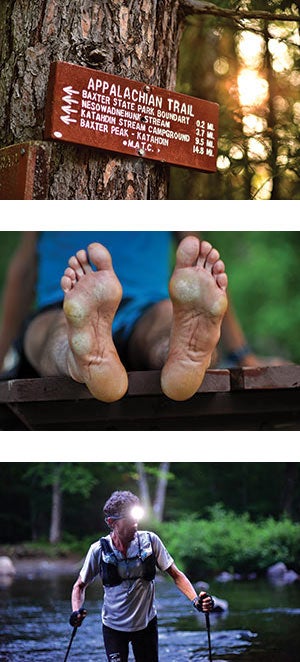

Scott Jurek was stuck in the mud. In late June, the veteran runner was a month into the longest run he’d ever attempted—the 2,189-mile Appalachian Trail from Springer Mountain, Georgia, to Mount Katahdin, Maine. After a few early setbacks, Jurek was regaining ground, once again on pace to break the standing speed record of 46 days 11 hours 20 minutes.

Then he hit Vermont. The state’s characteristically soft ground—“They call it ‘Vermud,’” Jurek says—had been turned to complete slop after an unusually wet spring. The tedious slog, far more walking and slipping than running, was some of the slowest movement Jurek had ever experienced. Day after day, he spent extra time and energy, and cut back on sleep, trying to cover enough distance to stay on record pace—and he was still losing time.

It didn’t get any better across the state line, either. The rocks and roots of New Hampshire offered no reprieve. Jurek was running out of time and mental reserves.

And for the first time in a while, there was no place he would have rather been.

Before he became the elite endurance athlete who won the Western States 100-mile Endurance Run seven straight times between 1999 and 2005, before he even trained on trails, Jurek, now 41, found solace in the outdoors. Growing up outside Duluth, Minnesota, he often ran or skied as a way to reset and recharge in the face of personal setbacks.

“I’ve never used the trails to run away,” says Jurek, who lives in Boulder, Colorado. “They are a source of strength and reflection that allows me to grow and understand life.”

When his mother ailed with multiple sclerosis during his high-school years, Jurek chased his friend Dusty “Dustball” Olson, then the superior athlete, through the cold northern woods. Spurred on by Olson, he ran longer and longer, eventually entering his first 50-mile race—where he beat the Dustball for the first time.

In the early 2000s, Jurek trained in the lush mountains outside Seattle, then his home, for the bulk of his Western States wins. He followed that streak with two straight wins at the 135-mile Badwater Ultramarathon, a road race in Death Valley, in 2005 and 2006; a course-record win at Colorado’s Hardrock 100 Endurance Run in 2007; and three consecutive victories—2006, 2007 and 2008—at Greece’s 153-mile Spartathlon.

But then his racing became less requent, his mother died and his first wife left him, and the trails didn’t seem to go anywhere. In 2010, seeking sun and a change of scenery that would reinvigorate his running, Jurek relocated to Boulder. There, he shared time in the Rocky Mountain foothills with Jenny Uehisa, whom he had met in Seattle and started dating in 2008. The trails were a place he could go to try to remember what mattered, what made him happy—why he was doing all this in the first place.

But in those days, the trails led to questions more than answers. What did make him happy? Why did he do all this? As his racing schedule quieted down, no one seemed to know—least of all Jurek himself.

In 2010, Jurek set an American 24-hour record. He placed 23rd at the Chuckanut 50K in 2011 and came in eighth at the 2013 Leadville Trail 100, with no race results in between or since. It was a far cry from his peak racing days, and surely not enough to satisfy someone who had made a career out of pushing his limits.

“I’m at the point where racing doesn’t motivate me,” says Jurek now. “It’s an awesome and amazing way to explore one’s potential. But our passions and how we experience those things change.”

Jenny sensed that his heart hadn’t been in it for a while. “I’ve seen him at all these 24-hour things and Leadville, but there wasn’t a joy about it,” she says. “It seemed like he was trying to convince himself he was enjoying this and wanted to compete.”

Jurek was finding that, more and more, he simply enjoyed spending time outside with Jenny. The two of them hike regularly in Colorado, and spend about a week each year trekking 100 or so miles of the Pacific Crest Trail, or PCT. (Jurek jokes that he and Jenny are on the “25-year finishing plan” to complete the entire trail.)

“It was just a way to be out in the woods and spending time in nature,” says Jurek. “You unplug and don’t think about other things for the week or weeks you’re on the trail.”

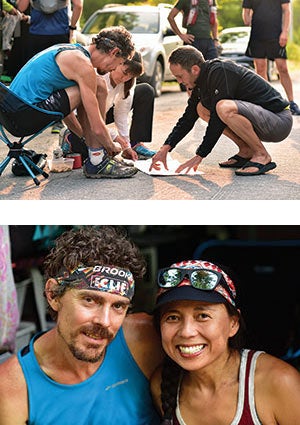

In 2012, he and Jenny married. That same year, Jurek’s best-selling autobiography, Eat & Run, came out. With racing out of the picture, and book royalties and speaking fees to pay the bills, he threw around the “R-word”: retirement. He and Jenny made plans to start a family, and in the spring of 2014, they were expecting.

That May, however, Jenny miscarried. Their plans suddenly pulled out from under them, the couple went back to the PCT. Once again, Jurek says, he could “use the woods and the wilderness to reflect on things. Not to forget about them, but to spend some time without them constantly in the back of your mind.”

“We wanted to get away from the hospitals and the sorrows, go into the woods and reconnect,” says Jenny. “We wanted to get a fresh outlook on life. That’s what we always did.”

On the trail, free from the shadow of his racing career and the clutter of book tours and speaking engagements, Jurek’s mind returned to long-dormant “passion projects.” One such project was to complete a National Scenic Trail. Long thru-hikes had always intrigued Jurek; a 1,000-plus-mile trek would be more challenging and solitary than any 100-mile trail race.

“I’ve been mesmerized by going on these long journeys and going for a fast effort,” he says. “I wanted to experience that.”

Around that time, Jurek told Jenny he was considering the Appalachian Trail speed record. This new goal caught Jenny off-guard. They were regulars on the PCT, but had no real connection with the AT.

“The PCT did seem like the obvious first choice for a thru-hike or a speed record attempt, since we’d spent so much time out there,” says Jurek. But he wanted to keep exploring the PCT bit by bit with Jenny. “So the AT came up. I’d only seen about 30 or 40 miles of it at that point, and it seemed like a neat adventure to go and try to do the whole thing.”

Plus, Jurek reasoned, the PCT’s sections were long and isolated, while the AT had innumerable road crossings where he could meet Jenny. It was something fun the two of them could do together.

“That’s how he framed it, anyway,” Jenny says. “I think we both had no idea. I had no idea how rugged or remote it was, or how desperate it was going to be at times.”

—

Jurek’s idea of a “neat adventure” was 2,189 miles through 14 states, starting in Georgia and ending atop Mount Katahdin in Maine. Ubiquitous rock, gnarly root systems and relentless climbs and descents—the total elevation change, 515,000 feet, is roughly twice that of the PCT—have defeated many a would-be thru-hiker.

“The AT is a lot tougher than the PCT, Colorado Trail or any other route,” says prolific 100-mile victor Karl Meltzer, 47, of Sandy, Utah. Meltzer grew up in New Hampshire, hiking nearby sections of the AT, and has twice attempted the fastest known time, or FKT. “It’s technical, rocky, rooty, very steep, slick, endless. [There are] bears, moose, marshes, bogs, big river fords,” he continues. “It spits people out because they don’t realize what they are getting into if they only look at maps.”

When Jurek started the trail in May, the FKT was held by Jennifer Pharr Davis, of Asheville, North Carolina, who in 2011, at age 28, completed the AT in 46 days 11 hours 20 minutes. There might be no better illustration of the trail’s technical, slow-moving nature than the fact that Pharr Davis set her record without running a step—and, in so doing, beat the times of several men who had run at least part of the way.

“My approach was simply to cover as much ground as I could, as efficiently as I could,” says Pharr Davis, now 32. “The reality of this trail is that you’re definitely going to hike at least half of it.”

After Jurek mentioned the AT to Jenny in May 2014, they decided to travel there the following year. Then, in early 2015, Jenny became pregnant a second time. Again, they focused on planning their family.

“We thought she would be pregnant while I was out on the trail,” Jurek says. “We thought it wouldn’t be too bad, mostly hanging out in the van. Not a vacation, but there would be a lot of down time.”

But in April, Jenny miscarried a second time. They decided to stick to their late-May departure date for the AT. “It was like, ‘We need to do this now,’” Jurek says. “We needed to process what happened.”

Unlike his reflective hikes on the PCT with Jenny a year earlier, the AT became a goal in and of itself. Jurek had found a new way to push himself into unknown places.

At 5:56 a.m. on May 27, Jurek set out from Springer Mountain, Georgia, the AT’s southern terminus. When she saw him at road crossings that first day, Jenny noticed something different. She had seen her husband trudge through plenty of races as if they were obligations. But that day, Jenny says, “He looked like he was genuinely having fun. I was so psyched to see that spark and that freshness in his face.”

At 5:56 a.m. on May 27, Jurek set out from Springer Mountain, Georgia, the AT’s southern terminus. When she saw him at road crossings that first day, Jenny noticed something different. She had seen her husband trudge through plenty of races as if they were obligations. But that day, Jenny says, “He looked like he was genuinely having fun. I was so psyched to see that spark and that freshness in his face.”

And alongside the FKT—a goal that would require him to run between 48 and 56 punishing miles every day—fun was a priority for Jurek. He took in the scenery and stopped for leisurely half-hour lunch breaks with Jenny.

“Some would say I was wasting time,” he says. “I didn’t treat it as every second of every day counts, because I wanted to stay balanced. It was a record attempt, but I also wanted to see this big, beautiful trail.”

Leaving some details unplanned, they ran into early logistical challenges. A GPS device didn’t work, and cell coverage was nonexistent in the woods, complicating communication. Jenny had to navigate to road crossings with a paper map, then dash into nearby towns to stock up on fresh produce, greasy diner potatoes and whatever else she could scrounge up to supplement the nutrition products and vegan ingredients crammed into their van. When Jurek’s day was done, Jenny was figuring out logistics for the next.

Friends and fellow runners accompanied them at different stages: Meltzer; Krissy Moehl, another elite ultrarunner, who, in September, would set a new FKT on Califonia’s Tahoe Rim Trail; David Horton, a previous AT record holder; Luis Escobar, a close photographer friend of the Jureks; and others. The support made Jenny’s difficult task easier.

“We were pretty disorganized, but when Meltzer and Horton got there, they righted our ship since they were veterans of the AT,” says Jenny. “They were like NASA scientists with their spreadsheets.”

Meltzer and Horton kept Jurek moving when he’d stop for lunch—they’d tell him to eat while walking. Occasionally, they even acted as crowd control when fans from the running and vegan communities, following Jurek’s progress on social media, came out to meet their hero, run with him and take photos.

“A few times I pushed people back and told them to wait till he’s ready,” Meltzer says. “It was invasive at times, but he was very gracious with people, a real professional.”

Running 60 or 70 percent of the time at the outset, Jurek had gotten a jump on Pharr Davis’s ghost. But in Tennessee’s Great Smoky Mountains, less than 300 miles in, he came down with patellar tendonitis in his right knee and, compensating for the injury, quickly acquired a quad tear on his left side. After just seven days, he was running on two bad legs.

“I thought for sure we were done,” Jurek says. His crew took him into town for a rare night in a hotel. Horton told him to try hiking the next day; he could still get to a trailhead 37 miles away, then reevaluate. Jurek wouldn’t break the record on 37 miles per day, but he had a big cushion over record pace.

Walking felt OK, and was all he could manage the next few days. Going easy, he hoped, would let his injuries heal while still allowing him to put in enough miles.

“I’ve been doing this enough years that my body has a great ability to recover,” he says. “Soon I was doing 50 miles a day and the pain was decreasing gradually.”

In a way, he relished the constant ups and downs. “The beauty of something long like this is you’re going to hit a low point, but you can crawl out of it,” he says. “It’s part of the ebb and flow.”

Horton says Jurek’s attitude was surprisingly positive under the circumstances—but didn’t know if it would be enough.

“Scott has run, and won, some really long, tough races, but he’d never done anything nearly this big, this long,” he says. “It was going to take everything he’s made of.”

That test came in the last 10 days. Jurek’s cushion over the record dwindled as he battled Vermont’s mud, New Hampshire’s rocks and roots and an unidentified, energy-draining sickness crossing into Maine.

Jurek woke up around 5:30 a.m. on Sunday, July 12—Jenny’s birthday—after an hour of sleep. He had until 5:15 p.m. to cover the 18 miles to Mount Katahdin’s 5,270-foot summit, the trail’s endpoint, and break Pharr Davis’s record.

After arriving at the base of the mountain with hours to spare, the Jureks spent Jenny’s birthday hiking the five-mile summit trail with some friends, as Jurek describes it. They moved at a good but relaxed clip. For the first time, he felt confident the record was his, and could savor the beautiful climb and good company.

Just after 2 p.m., the group reached the summit. Jurek had completed the AT in 46 days 8 hours 7 minutes—a new record by about three hours. Jurek, alongside his crew and a crowd of hikers who had climbed the summit to see him finish, popped open a bottle of champagne, enjoyed the view and hiked down.

That champagne caused a headache as soon as Jurek reached the trailhead. Baxter State Park rangers waited with citations for drinking alcohol in the park, littering (because champagne had splashed on the ground) and hiking with an oversized group, even though most of the summit crowd had hiked up independently. In September, Jurek paid a $500 fine for drinking as part of a plea deal to drop the other two charges.

Worse than the fine, to Jurek, was the rebuke it represented. Shortly after his AT finish, Baxter officials castigated him on the park’s Facebook page. They wrote that Jurek had held a “corporate event” that was “incongruous with the Park’s mission of resource protection, the appreciation of nature, and the respect of the experience of others in the Park.”

Jurek defended his FKT celebration as a grassroots event, its fanfare due to social media and word-of-mouth rather than a well-oiled corporate hype machine. He questioned whether citing him was an effective way to bring attention to overcrowding and its negative effects on open spaces.

“It’s unfortunate they tried to draw attention to it that way,” he says. “My goal was to inspire others, and to do it in a respectful manner toward the land.”

The controversy was especially bizarre because in many ways Jurek—who has long adhered to Leave No Trace ethics—embodies the values Baxter officials were ostensibly trying to promote.

“Say what you want about Jurek, but he’s the last guy you need to teach about littering,” says Olson, Jurek’s childhood friend and training partner. “If you wanted to beat him in a race, all you had to do was drop some garbage in front of him and take off sprinting, because he’d stop and pick it up every time.”

Pharr Davis, though naturally a little disappointed to lose the record, was happy that Jurek was the one to break it. “Scott is such a great ambassador for trails, and for a healthy lifestyle,” she says. “And he got way more coverage for his record than I did. I’ve actually been interviewed more times for losing the record than I was for getting it in the first place.”

Treading lightly on trails and in the wild places that surround them is more than a priority for Jurek; it’s a reflex. It’s also likely to form the basis of his post-racing career.

“I’m just as excited by speaking and writing, and being part of the outdoors and running community, as I was by competition,” he says. “It’s about giving back, inspiring and being inspired by the stories I hear—about people getting off the couch and surviving chronic disease, or about how running trails turned their lives around.”

There may be another book, but probably not soon. Another major thru-hike could be in the cards, though not at the same level. And, the Jureks hope, a family.

Whatever Jurek’s future holds, the trails will be there. “What fires me up is a two- or three-hour run in the mountains, or backpacking with my wife,” he says. “I’m drawn to the trails because they’re a challenging place, and I’ve taken on a lot of difficult tasks, but they’ve also taught me a lot … They’re really woven into the fabric of my life, whether I expected them to be or not.”

Alex Kurt is also contemplating retirement. He is 28 and lives in Minneapolis. This article originally appeared in our December issue.