Running Roots

Tom had warned me that the turnout would be low but I was buoyant as I bumped down the rutted red road to the race grounds in Asaayi, New Mexico. I had no idea this beautiful place existed. An hour earlier I’d left my home in Shiprock, on the northeastern edge of the Navajo Nation. I drove through familiar dust, tumbleweeds and glaring, relentless sun. But, following Tom’s directions, I turned off the highway, climbed into the Chuska mountains and arrived at this picturesque lake. Ponderosa pines scented the damp air. I craned my neck back to take in the full imposing height of the sandstone cliffs. As I pulled into the staging area, I mentally planned a return visit to hike and swim with my kids.

It was easy to find Tom Riggenbach in the small crowd. A head taller than anyone else, visor shading his eyes, he constantly bobbed and moved, encouraging runners, emptying trash cans, filling food trays and delegating to volunteers. This was the first ever “12 Hours of Asaayi,” the newest addition to the Navajo Parks Race Series that Riggenbach, executive director of the nonprofit NavajoYES, puts on. The race course was a 2.4-mile trail loop that he’d rehabilitated over the summer with a group of 8th-grade boys from the reservation town of Chinle, Arizona.

Originally from rural Illinois, Riggenbach has lived on Diné Bikéyah, the Navajo Nation, for 30 years. He taught school for most of this time and organized the youth-empowerment organization NavajoYES on the side. Now he runs the nonprofit full-time from a community center in Beclabito, a 600-person town on the New Mexico-Arizona border. Riggenbach lives in its small office, having moved his cot there after he quit teaching in 2015. From there, nestled between the red rock of Beclabito Dome and the extinct volcanoes of the Carrizo Mountains, he organizes trail-running and mountain-bike races, and youth outdoor activities.

“It’s a pretty sweet set-up” he says. He is grateful that they have a storage shed out back for donated bikes and helmets, boxes of race T-shirts and medals. He doesn’t mind that graduation parties and local council meetings happen right outside his bedroom door, or that he sometimes has to stand in line for his bathroom.

I met Riggenbach about nine months earlier, when, on a whim, I entered a race at the Four Corners Monument. I had lived near the Four Corners for a decade, but had been to the monument only once, eight years before. I remembered stray dogs picking through trash while my cousins straddled New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado and Utah and posed for goofy photos. I hadn’t been back since. Then I saw a Facebook post about the Quad Keyah: four days of trail marathons and half-marathons, one in each state. There were running trails there?

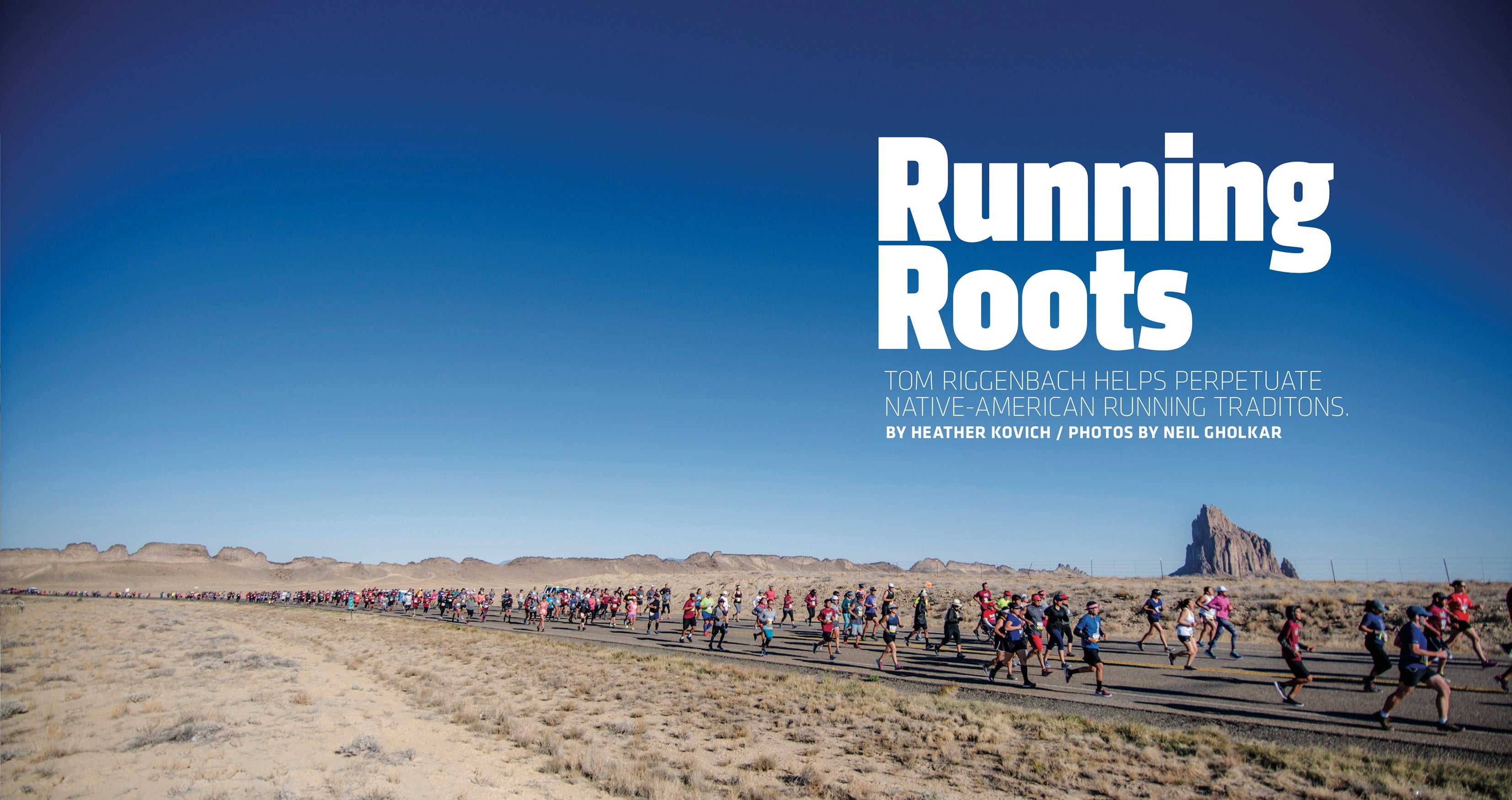

At the Quad Keyah race, people laughed and talked like old friends in the registration tent. There was a mix of Navajo runners and people from all over the country, many pursuing a 50-state marathon goal. Riggenbach gave a pre-race informational pep talk each morning, giving the usual route and weather information but also calling out notable runners: those who’d run well the day before, those celebrating a birthday, the 10-year-old running his first half-marathon. I wondered about this white guy, sun weathered and unshaven, who seemed know everyone.

The race itself was painful: rocky, sandy and steep. But its course revealed the landscape’s majesty—eons of geology displayed in the slickrock mesas and the cut of the San Juan River below. The runners on the trail smiled and encouraged each other. Tom was out chatting and jogging with different people all day. I didn’t even mind (much) when I limped across the finish line of the Colorado Trail Marathon and Josh, the timer, told me to keep running—they’d misjudged the distance and I still had a mile to go. I went home and registered for the NavajoYES Monument Valley Ultra. The next time my parents came to visit, I took them hiking on the Four Corners trail.

Riggenbach founded NavajoYES in the early 1990s when he was a teacher at a small school in the reservation town of Shonto, Arizona. Each summer he led his students on a bike tour of the 27,000-square-mile Diné Bikéyah, a chance for them to spend time outside and get to know their land, with its canyons and mountains, windswept open range and towering rock formations. NavajoYES—the YES stands for Youth Empowerment Services—was initially a way to raise money for these trips, which Riggenbach called The Tour de Rez.

Riggenbach was not a runner when he came to the Navajo Nation; he was a cyclist. He had just graduated from college with a teaching degree, and his mentor, who had taught briefly on the reservation, encouraged him to push his boundaries further than Peoria, the town closest to where he grew up.

“He’s like, ‘Just get away for a year,’” Riggenbach remembers. He sent a resume to Shonto Boarding School. They called him on a Monday in August and the following week he was in the classroom teaching third grade.

He’d planned to stay for a year, but, “It was pretty cool place. It’s gorgeous out there and it’s so quiet,” he says. He felt at home in the rural setting. He’d grown up on land that had been his grandparents’ farm, which they’d divided between their children. He was surrounded by cousins.

“All the neighbor kids, we’d go out and play whatever sport was in season … just play till dinner time. And then go back out for a couple of more hours.” In Shonto, he found a similar community structure, with extended families full of “cousin-brothers.” And in Shonto, where the vast, sparsely populated land inspires long distances, Riggenbach learned to run.

For centuries, the Navajo have kept a tradition of waking and running east to greet the sun. While the tradition is not daily practice for most people, “Everyone has a running story,” says Riggenbach. Schools start cross-country teams in 2nd grade. The Kinaaldá, the coming of age ceremony for girls, includes a daily sunrise run. The girl, representing a deity, the Changing Woman, runs in moccasins and turquoise jewelry. Her family runs behind her, encouraging her, pushing her to go a little farther. The daily distance is often a mile or more.

Desiree Deschenie, 30, of Farmington, New Mexico, was 10 when she completed the ceremony. “It’s 5 a.m. and I was running in full traditional clothing … and everyone was shouting for me,” she says. “I felt that I had a really important role to do.” She laughs remembering that she kept telling herself, “Just don’t fall!”

She became a cross-country runner after that. “The Kinaaldá gave me the idea that running is very important and very sacred.” As an adult she’s participated in the Shiprock Marathon, a NavajoYES race. “Their series of races highlight the beauty in the area.”

In a land where less than 20 percent of the roads are paved, being a runner means running on dirt. “When I came to Shonto, I discovered, ‘Hey, this is a totally different kind of running,’” Riggenbach remembers. “I started running quite a bit and did a lot of trails all over the western rez.” Navajo Nation abuts the Grand Canyon. “I did a lot of rim to rims, double crossings, stuff like that.”

He taught all week and, on the weekends, despite being hours from an airport, managed to complete sub-four-hour marathons in every state between 2005 and 2015. In 2014 he moved on to ultras. The annual Tour de Rez began to incorporate several days of trail running.

NavajoYES expanded its scope over the years and in 2015 Riggenbach quit teaching to focus on the nonprofit full time. He and Rygie Bekay, a 23-year-old former-student-turned-colleague, now bring outdoor-fitness programs to schools, teach kids to repair bikes and work with local communities to build dedicated trails for running, hiking and biking all over the reservation. They partner with Navajo Parks and Recreation to host races that highlight the trails. Some races are in famous and popular locations like Monument Valley. Others bring runners to little known areas like Lake Asaayi.

When I met up with Tom at the Asaayi race, he wanted to show me the trail work by the Chinle students. We started toward the trail many times, but he kept getting pulled back to the staging area. When food and trophies were finally organized and we were ready to go, Scott Nydham, a volunteer and NavajoYES board member, reminded Riggenbach they needed to meet about logistics for an upcoming race. Nydham and Riggenback live on opposite sides of the Navajo Nation, 150 miles apart, and this was their only chance to hash out the details in person before race day.

Eventually Riggenbach and I got out onto the course. The trail was well graded and easy to follow up gentle switchbacks. Tom jogged with four gallons of water and a backpack of Honey Stinger bars to resupply the aid station at the top. He kept stopping. I offered to take some water, but the load wasn’t the problem. “Sorry about that,” he apologized when he caught up to me. “I got a signal back there and I had to send some messages.” This is why he’d had to organize with Nydham face to face.

Much of the reservation has spotty cell service and no internet, including the NavajoYES offices in Beclabito where the lack of lack of internet is a constant problem. Riggenbach wants the races to be accessible. He puts his personal cell number and email address on every registration page, but he needs to be able to retrieve the messages. He often drives 20 miles to the McDonald’s in Shiprock, where a dollar buys a hot coffee and fast Wi-Fi.

As we jogged up the trail at Asaayi, Riggenbach unwittingly ruined my plan to come back and hike with my kids when he lamented that the trail is closed to the public except during official events. He understands the concerns from Navajo Nation Parks and Recreation. “One, they’re worried about liability and, two, they’re worried about knuckleheads coming in here and jacking up the place.”

We met a family on the trail. They’d come to cheer on Amanda, one of the runners. She is from the reservation but lives in Phoenix and often drives the six hours back for NavajoYES races. “She just looks so effortless out there,” Riggenbach told her father. “Just so steady.“

He resumed his train of thought on public-access trails. “I’m trying to figure out how to answer that concern without going crazy.” He thinks a gate across the road with a pedestrian entrance a quarter mile from the trailhead would work. “I don’t know too many knuckleheads who are going to go that trouble to drag their 40s that far.”

Riggenbach likes working with Parks and Rec, and he is optimistic they’ll agree on a plan to open the trail for everyday use. Matt Gunn, 42, of Willard, Utah, who operates Vacation Races, has always been impressed by Riggenbach’s ability to build local partnerships. “When you get a permit to run on Navajo land, it requires talking to the families that have the grazing rights and the local residents, as well as the Parks Service and the Navajo Nation. Through years of work, Tom has those relationships. They know when Tom’s doing something, it’s solely for the benefit of their community.”

Riggenbach and I reached the top of the trail, where we could see the staging area and finish line. The band, Red Hawk, of Montezuma Creek, Utah, ricocheted Creedence Clearwater Revival off the cliffs. “They will play all day.” Riggenbach appreciated their enthusiasm. He’d paid them $200, figuring it would cover their gas money, and they were happy to blast a classic rock soundtrack for 12 hours.

Blaze Braford-Lefebvre, a 17-year-old, limped to the aid station. He rolled his ankle in a previous lap and was weighing his options. “Should I pull a Kilian Jornet?” he joked, wondering if he should gut out the remaining six hours on a gimp ankle (Jornet had run much of the 2017 Hardrock 100 with a dislocated shoulder, winning the race). Riggenbach reminded him that there were EMT’s at the staging area. He rested for a moment and jogged off.

As we ran down the far side of the loop, Riggenbach pointed out the absence of mud on the trail. A thunderstorm had rolled in the night before while they were out preparing for the race and it turned into an opportunity to check the trail conditions. “We were out here with McCleod rakes, clearing the drainages in the rain,” he said proudly.

When we got back down to the staging area, I asked Bekay how he’d liked working in the thunderstorm. “Oh, that was just Tom,” he chuckled. Bekay and the other volunteers had gone back to camp shortly after it started raining. I’d noticed that Riggenbach always uses “we” to speak of his work, a pronoun brimming with optimism.

I spotted Braford-Lefebvre sitting on a cot as the EMT brought him an ice pack. He was done for the day. His younger brother Soren was still out running. Their family drives down from Silverton, Colorado, a trail-running mecca, for NavajoYES races. “We love the desert,” Blaze explained with a wide smile, “and we love Tom’s races. The energy is so good.”

I realized it had gotten quiet. Only the drummer was still playing; the rest of the band milled around. A singer wandered my way and asked if I had a rubber hose. Their generator had run out of gas and they needed a siphon. I had no hose, but 20 minutes later they were playing again. I squinted at my gas tank. Maybe $200 wasn’t quite enough gas money.

NavajoYES operates on donations and a few grants. They don’t make much money off of their races; they keep the entry fees as low as possible to maximize accessibility. Some of their bigger marathons yield a small profit, but the Asaayi race had only drawn 13 participants, 12 of whom Riggenbach knew personally. After paying for the EMTs, food, port-a-potties, race T-shirts and pint glasses, it would not be a money maker.

Riggenbach works hard to keep costs down. Before coming to Asaayi, he had a meeting with the United Way in Window Rock, Arizona. He had meetings scheduled over two days so he brought his cot and slept in their offices overnight. I asked if they minded. He laughed. The United Way funds some of NavajoYES’s budget. They were thrilled he didn’t expense a hundred-dollar hotel room with their grant.

Riggenbach doesn’t get paid for his work, although he’s quick to point out that his rent (the floorspace for the cot) is covered and his gas money gets reimbursed. Otherwise, he lives off of his teacher’s savings. He’s bashful about this, worrying that people will take his work less seriously if he’s “just a volunteer.” Bekay balances NavajoYES with a full-time job and school— “That kid can work!” says Riggenbach.

“The one thing I wish we could get better at is fundraising.” Riggenbach is forthright. Matt Gunn has raised money for NavajoYES just by having a donation link on his registration website. Riggenbach would like to emulate that. “I think if we took the message to all the non-rez runners and said, ‘Hey you know, we’re trying to promote health and wellness and we have these projects.’ I think we could do it. I mean, part of our problem is just having someone who’s got the tech skills and the time to do the website stuff.”

It irks him to see other organizations raise money by highlighting the poverty on the reservation. “‘Oh, diabetes is horrible here; healthcare stinks.’ You know, that plays real good … then they get more donations, but I don’t know, we never really tried to play that card.”

“It’s true, diabetes is a problem. Obesity is a problem,” he continues, “but if you just go on and on about it, it not only becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy, it becomes a real downer for the folks living here. They’re like, ‘Dang.’” He looks at the ground and shakes his head, impersonating the despondency.

He prefers to be an optimist. “We’ve got a lot of exciting things happening around the area … Every year we’ve got more races and runs. I mean there’s literally something almost every weekend somewhere on the rez, which is pretty remarkable for a population of this size … Rather than dwelling on all these dire stats, we portray a little happier place.”

He knows the standard narratives of reservation life but he appreciates the complexity, the struggles and the resilience. He taught in the schools for 25 years. He witnessed the traumas of his students and also saw them persevere. He’s also sensitive to the fact that 30 years in, he’s still an outsider, a biligaana.

“We’d have more impact if I was ‘Tom Begay,’” he says, citing a common Navajo surname. “I feel like there’s a little sense from some people: ‘Oh, he’s a missionary’ … Even though I’m a white dude, hopefully, people see me as just Tom.”

It chafes when outsiders ask, “‘So how are things on the reservation? … You know, you’re doing such good work.’ …. I’m just living, you know? I mean, no matter where you are, hopefully you’re trying to improve life and make things better for folks.”

He admits that when he arrived on the reservation, “I may have had little bit of a missionary mindset.” After all, he’d chosen to teach after seeing the movie Stand and Deliver, in which a high-school teacher inspires impoverished Los Angeles teenagers to master advanced calculus. “Dang! That changed everything. The teacher changed the whole neighborhood and the whole community.”

After 30 years in education and nonprofits, he laughs. “I don’t know if that’s really worked out, but that was the way I was thinking, and I’ve pretty much stayed in education and nonprofit stuff since.”

As Riggenbach presented plaques to the winners at Asaayi, runners sat exhausted, on cots and folding chairs, waiting for the masseuse. Aury Yazzie, 11 years old, shook my hand solemnly, manners intact even after finishing the six-hour race. His mother proudly explained that Aury has known Riggenbach his whole life and has grown up running these races.

Dylan Schwindt and Mike White had come down from Cortez, Colorado. Like Blaze’s family, they make an effort to drive to the reservation for NavajoYES races. Schwindt pointed out that the races immerse him in the beauty of the reservation. “Like in the Monument Valley Ultra, you get to go up Mitchell Mesa,” he said. Mitchell Mesa is a 1500-foot climb in less than a mile, but the top presents a panoramic multi-state view of one of the American West’s most iconic locations. Back at the bottom, runners scarf down quesadillas at Lorraine’s sheep corral and get directions from ranchers on horseback. Tourists, meanwhile, are confined to the paved roads.

Schwindt didn’t mind that there weren’t many participants at Asaayi. “Sometimes really elite runners show up,” he says, “and that’s fun because you get to run with them. But sometimes the turnout is low and you hit the jackpot.” His winner’s plaque stood on the table next to him.

Riggenbach’s goal is to get the community, his community, outdoors, to marvel at the majesty of the land that is their birthright, and to take pride in the feats their bodies can accomplish.

Heather Kovich is a family doctor who lives and runs in Shiprock, New Mexico.