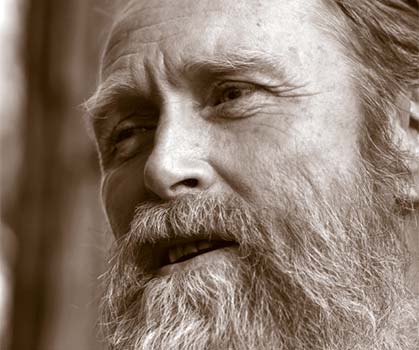

Gordy Ainsleigh, Runnin' Rebel

This article originally appeared in the July 2005 issue of Trail Runner.

Under Gordy Ainsleigh’s puffy, Charlton Heston-esque beard (a la the film Ten Commandments) hides a mouth glued in a perpetual smirk. It is partly mischievous and partly the grin of an omniscient sage who sees profound truths.

It also holds a speck of mystery. Says long-time friend and vice president of the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run Shannon Weil, “Gordy definitely lives in his own orbit.” And that is fitting, given Ainsleigh’s otherworldly claim to fame: over 20 years ago, he ran 100 miles of trails in one day, thereby planting the seed for today’s most extreme trail ultramarathons and, more specifically, the Western States 100.

At 58 years old, Ainsleigh is seasoned enough to remember the days before trail running’s current boom. Long before the days of specialized trail-running shoes, Scott Jurek’s 100-mile records, wicking clothing and energy gels, Ainsleigh ran beyond what anyone imagined possible.

“We are all here to do something,” he says, leaning over a campfire in California’s Sierra Nevada Mountains, “and I really believe I was put on this Earth to start trail ultrarunning.”

As flames flare up and lick his whiskers, Ainsleigh shares an outlandish tale that at first elicits chuckles. “At the end of the 19th century, the Father, Son and Holy Ghost above conspired to urge more people into the outdoors,” he explains with conviction, “so they bestowed upon humankind skiing and horseback riding.

“Years later they checked to see how their plan was working,” Ainsleigh says, “and realized humans were still screwing it up, and they needed to push people into the wilderness with nothing at all–just their feet.” That, says Ainsleigh, is why he was created.

“But the gods didn’t want me to be a happy kid,” he says, “so they broke up my parents and forced my mom and grandma to raise me alone.” As a result, Ainsleigh essentially had two mothers. Says Ainsleigh, “They made me wear long underwear into June, and it all came together to make me a separate and peculiar person.”

A young Gordy lived nearby his elementary school and, over lunch one day, his rebellious spirit blossomed and compelled him to run home. “It was a mile through the woods and across a creek,” he recalls, “My grandma was at home and she treated me like a hero.” He ran back to school, too.

Time warping forward into the early 1970s, Ainsleigh found himself back in the Sierra Nevada after detours through Vietnam and Santa Barbara, California. While at the University of California, he had bought a horse (“He threw me three times before I said, ‘I’ll buy him.’”) and learned of an event called the Tevis Mountain Cup, one of the country’s premier horseback riding competitions that traversed 100 miles of sweltering, rugged trail.

Ainsleigh and his steed, “Rebel,” galloped the race in 1971 and 1972, before the gods intervened once again. “After the 1972 Tevis Cup, one of the finest pieces of female fluff took my horse,” says Ainsleigh, sounding like a country music song. That misfortune, he explains, set into motion a string of events that delivered Ainsleigh to his destined day.

Ainsleigh got a new horse, but it went lame on a training run before the 1973 Tevis Cup, forcing him to sit out the event. Referring to the man who knowingly sold him the lame-horse lemon, Ainsleigh says, “That level of character decrepitude was necessary for what came next.”

1974 saw Ainsleigh horseless as the Tevis Cup approached. What did he do? He participated in the race sans equine.

Ainsleigh ran the 100-mile mountain course in under 24 hours—the time standard set for Tevis Cup racers—and the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run was born. A more formal, inaugural Western States run didn’t take place until 1977, but Ainsleigh’s trot is widely recognized as the event’s first running.

One person who remembers Ainsleigh’s famous run is Jim Edwards, a retired veterinarian who monitored the health of the horses that day. “You had to be there to realize how nuts this whole thing was,” he says. “Here was this guy who could easily hop on a healthy horse, but he chose to run.”

Weil echoes Edwards’ awe of Ainsleigh’s exploits: “It was the landmark event that established the sport.”

Today, Ainsleigh still runs the Western States every year. He is a practicing chiropractor and lives in Meadow Vista, California, a short run from the Western States finish line in neighboring Auburn. He exudes the strong-mindedness and abundant energy of the long-haired kid he once was. “I never want to be sane,” he says, “’Still Crazy After All These Years’ should be my theme song.”

True to his word, Ainsleigh runs the trails with his hair flowing and his shirt off. He’s just slowed down a bit … but not much. “My friends keep expecting me to calm down–quit rock climbing, quit flirting and quit taking all those chances,” he says, “I guess I just don’t get it!”

Then Ainsleigh unpredictably turns poetic, quoting the flamboyant and boisterous Dylan Thomas: “Old age should burn and rave at close of day … Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

The 2005 Western States 100 will take place on June 25. Look for Ainsleigh out on the unforgiving course, where he’ll attempt to complete the race for his 20th time.