New perk! Get after it with local recommendations just for you. Discover nearby events, routes out your door, and hidden gems when you sign up for the Local Running Drop.

Eight people who’ve been blazed new ground, from a 100-miler pioneer to the grand master of Pikes Peak to a modern-day phenom

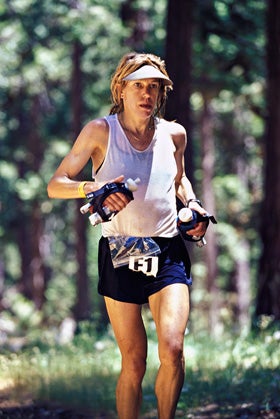

Trason shows the steely focus that made her unbeatable. Photo by Patitucciphoto

Ann Trason

A love of running

Ann Trason is the most successful female ultrarunner of all time. An alternative argument about the now-52-year-old is impossible: in the late 1980s, ’90s and first half of the 2000s, Trason racked up 14 wins at the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run (WS 100) and set gobs of ultramarathon course records. Many of these still stand, including her 1993 6:09:08 at California’s American River 50, her 1994 18:06:24 at Colorado’s Leadville Trail 100 and her 1997 22:27:00 at Utah’s Wasatch Front 100. A glimpse at her running history on Ultra Signup yields more evidence—there, 51 finishes are listed between 1985 and 2004 and 49 of them are wins.

Trason set standards that the women of ultrarunning are just now beginning to catch. Last summer, ultrarunner Ellie Greenwood finally broke Trason’s WS 100 record.

“Admittedly, it’s taking a while for women’s results to come close to Ann’s,” says Greenwood, “When people put Ann in a separate category, I think this is defeatist and unfair for her. She’s a female runner just like us and we should be trying to better her times and not saying, ‘But that was Ann Trason.’ Her records are proof of what we can achieve.”

Trason’s dominance is not surprising to those who know her well. UltraRunning magazine publisher, John Medinger, has been friends with Trason since 1987 and remembers her ethic: “Running was the principal focus of her life. She trained hard, and competed harder. She was, in one word, fierce.”

Medinger recounts, “At the Way Too cool 50K one year, Ann came upon fast ultrarunner Dave Scott not too far from the finish and asked him if he wanted to tie. Dave realized this was Ann’s polite way of saying, ‘Do you want to run in hard together or do you want me to beat you?’ The pair finished together.”

“The mental aspect of ultrarunning was important to her,” says journalist and trail runner Sarah Lavender Smith, who interviewed Trason in 1997 and 2008 and who became acquaintances with her through the east San Francisco Bay trail running scene. “I’ve heard her say multiple times that ultrarunning is a thinking person’s sport.”

Throughout her career—as early as college—Trason was plagued by injuries, including hamstring, knee and back issues. Lavender Smith says that Trason trained and raced with discomfort for many years.

Despite Trason’s once-full-time involvement in ultrarunning as a runner, race volunteer and race director of northern California’s Dick Collins Firetrails 50, she has since chosen to disappear from the scene. She declined to participate in an interview for this article, saying, “[I’m] not running, and it is hard to talk about it.”

Says Medinger, “Ann’s shy when it comes to talking about her running. it’s ironic because she’s incredibly engaging in interactions with friends. i never call her unless I have an hour to talk!” Medinger says Trason has turned her energies to road cycling as a hobby. “She rides double centuries, but just for fun.”

“Publicity or public praise has never been important to her. She ran because she loved it—the challenge, the competition, the adventure,” says Medinger.

Timeline

— 1985 > Ann Trason runs, and wins, her first ultramarathon, California’s American River 50.

— 1989 >Trason wins the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run (WS 100) for the first of 14 times.

— 1994 > Trason sets both the (now-previous) WS 100 course record and the Leadville Trail 100 course record, finishing second overall in both races.

— 1996 > Trason wins both South Africa’s Comrades Marathon and the WS 100, which are less than two weeks apart.

— 1996 > Doctors discover that one of Trason’s hamstrings is 90-percent detached and surgically repair it.

— 1997 > Trason wins both the Comrades Marathon and the WS 100 again. Trason tells journalist Sarah Lavender Smith that, due to her recovering hamstring, she is only able to train for these races at about 80 percent of her usual volume.

— 2000 > Trason and her husband, Carl Andersen, take over directorship of Dick Collins Firetrails 50.

— 2004 > The last ultramarathon result for Trason is listed on Ultra Signup, a win at the California’s Sierra Nevada Endurance Run 52-Mile. She is 44.

— 2010 > Trason and Andersen relinquish RD-ship of the Firetrails 50.

Carpemter in a Skyrunning race back in the day; he excels all altitude-a VO2 max of 90.2 doesn’t hurt.

Matt Carpenter

Jedi master of Pikes Peak

You can call Manitou Springs, Colorado, resident Matt Carpenter one of the world’s best trail runners. The 48-year-old has not only built his life around the sport, but has also helped build the sport.

Carpenter is married to Yvonne, a runner he met during a run put on by the Incline Club, a trail-running club Carpenter co-founded to help support and promote Manitou-Springs-area running. In 2000, the couple ran to their (on-trail) ceremony in Colorado’s Waldo Canyon. Their now-10-year-old daughter, Kyla, accompanied Matt on hundreds of training miles via her jogging stroller and has already run several races of her own.

Carpenter has lived at the base of Pikes Peak (14,114 feet), the hulking peak 10 miles west of Colorado Springs, for almost 15 years and trained on it more than any other human, ever. He has won the Pikes Peak Ascent six times and the Pikes Peak Marathon 12 times, most recently in 2011—you might call him the Jedi master of Pikes Peak. He’s both the ascent and marathon course-record holder (2:01:06 for the ascent and 3:16:39 for the marathon), both of which he marked during the 1993 marathon.

“Matt’s 2:01 Pikes Peak Ascent record is unreal. Probably a couple runners, like last year’s winner Mario [Macias], can run Matt’s splits to Barr Camp,” hypothesizes Simon Gutierrez, who has run the ascent seven times, won it three and has a 2:13:29 ascent PR. Barr Camp is located about seven miles from the start and at a little over 10,000 feet. From there, the course rises six more miles to the 14,050-foot finish line. Continues Gutierrez, “But at the altitudes above Barr Camp, there’s no one who can perform like Matt. Not yet. That record is going to last a while longer.”

Beyond the Colorado mountain, Carpenter’s pedigree goes on forever. He’s won and owns the course record for The North Face endurance challenge 50-mile championship, the Leadville Trail 100, the Barr Mountain Trail race, the San Juan Solstice 50, the Vail Hill Climb, the Imogene Pass run, the Everest Skymarathon and many more. He’s thrice captured the top spot at the Mount Washington road race and he’s championed a pair of Skyrunning race series in the 1990s. Oh, and he’s the world-record holder for running a marathon at altitude, putting down both a 2:52:57 at 14,435 feet (in 1997 at the Everest Skymarathon) and a 3:22:25 at an obscene 17,060 feet above sea level (also at the Everest Skymarathon but in 1995 when the race was held at an even higher altitude).

Carpenter’s racing success is built on good genes—his Vo2 max is an off-the-charts 90.2—and a sacrificing-most-things training ethic. carpenter tells the following story on the incline club’s website, which describes the depth of his training commitment: I had a rather upset stomach once on a day scheduled for a hard workout. So I did 30 minutes of one-minute hard, one-minute easy, on my treadmill [in the garage]. As the one-minute hard was coming to an end I would use the remote to close the garage door and sit on a bucket for a bathroom break because it was not possible to get to the bathroom and back that fast. Then I would quickly open the door for some fresh air and the next hard minute. I called that workout 30 minutes of one-minute hard, one-minute dump.

Carpenter’s connection with running doesn’t end there, as he’s the vice president of the Pikes Peak marathon, inc. Board of Directors. Says president and Pikes Peak ascent and marathon race Director Ron Ilgen, “Matt is the most passionate person i know about the mountain and its races. He’s also fiercely passionate about providing for elite runners at our races.”

Ilgen continues, “I remember the year I took over race directorship, 2002. Matt won the ascent in a time far slower than his record. The first thing he did after he finished was to tell me, ‘Look how slow I ran and won. I should have been beaten. We need to do more to bring in competitive athletes.’ We now offer elite entries, prize money and course-record bounties. He’s convinced me of the importance of these things.”

Timeline

— 1981 > At age 17, Matt Carpenter runs his first marathon, the Mississippi Marathon, in 3:11:11 (He improves his time to 2:41:23 at the 1982 race.).

— 1988> Carpenter wins the Pikes Peak Marathon for the first of so-far 12 times.

— 1990> Carpenter wins the Pikes Peak Ascent for the first of so-far six times.

— 1990> Carpenter’s VO2 max is recorded at 90.2, one of the highest ever for any runner, at the Olympic Training Center in Colorado Springs, Colorado. Recorded at just over 6000 feet elevation, the figure is undoubtedly higher when scaled to sea-level values. Carpenter in a Skyrunning race back in the day; he excels at altitude—a VO2 max of 90.2 doesn’t hurt.

— 1992> Carpenter runs the Olympic Marathon Trials in 2:32:26.

— 1993> Carpenter runs the Pikes Peak Marathon and simultaneously sets both the ascent and marathon course records.

— 2004> Carpenter races the Leadville Trail 100 (LT 100), his first 100-mile attempt, and finishes 14th in a painful 22 hours and 43 minutes.

— 2005> Carpenter sets the LT 100 course record at 15:42:59, avenging his previous year’s race.

— 2011> Carpenter wins the Pikes Peak Marathon, his most recent race, in 3:48:08.

In his element: Bauer orchestrating the Marathon des Sables. Photo by Audray Saulem

Patrick Bauer

In the beginning, there was Patrick Bauer and the Sahara Desert. It was January of 1984, and the young, former French-concert promoter had already spent a couple nomadic years exploring West Africa by car. In an effort to more deeply experience the desert, he undertook an almost-self-sufficient, 350-kilometer pedestrian expedition in southern Algeria. Bauer, then 26, carried all of his provisions save for water, which was resupplied from a car once daily by his brother and a friend. Twelve days later at the Niger border, Bauer emerged with a single thought: other people need to do what he just had.

Two years later, the first Marathon des Sables (MdS), a seven- day, six-stage, 250-kilometer running race of self-sufficiency (which means competitors carry everything they need for the week except water) was held in the more politically benign Moroccan Sahara. With 1986’s MdS, Bauer invented a new format: the stage race. Not even adventure racing had yet been born.

Twenty-three competitors undertook the inaugural MdS. Mário Machado, editor of Spiridon, a Portuguese running magazine, remembers that race well, “My biggest memory is a sense of aloneness, just 23 of us and the desert! For 10 kilometers at a time between checkpoints, I was alone on the unmarked route, using my compass for bearings. It was frightening, yes, but also exhilarating.” Machado has another vivid memory, “It was not easy in those days to find [backpacking] meals. I brought food out of survival packs, what’s stocked in lifeboats. It was horrible!”

The race grew wildly in popularity. In 1989, 170 competitors toed the line; in 2012, a throng of 854 jostled at the start.

“Patrick is the reason this race is so popular.” says Jay Batchen, the MdS representative who coordinates North American entrant registrations and who has finished the race eight times. “He wants every competitor to finish, but He also wants them to experience some sort of transcendent challenge.”

Getting the details of an expedition stage race in the remote and harsh Sahara Desert just right has always been tough. “In the late 1980s, the MdS was a unique event. We started from a blank copy,” says Bauer. each year offers up some unexpected challenge.

Batchen remembers the 2006 race not so fondly, “For unexplained reasons, hundreds of runners became sick. i woke up one morning and projectile vomited.” Such rampant illness threatened many runners’ ability to finish the race. Batchen says Bauer beefed up the race’s medical treatments and allotted competitors more water so they could recover and complete the race. “This was the first time i saw Patrick’s genuine concern for every participant’s experience.”

When asked about other unexpected challenges, Bauer’s response is instantaneous, “oh, 2009! The flood, a volume of water in the desert that i had never before seen! our ability to adapt has never been tested like that.” That year, the Sahara Desert experienced extreme flooding that shortened the race to four days and 202 kilometers, forced organizers to completely change the race route and provide for the safety of hundreds of competitors in cold, wet conditions.

The full-time mdS director, 55, married his wife, Marie, in 1998 after a long-term, live-in relationship, and the two have a 10-year-old son, Rayane. The family lives in France, but spends months each year in morocco. Bauer still runs, saying, with a laugh, “Well, I run when I’m not injured.” he also works on ecology projects in the Sahara, including building wells for remote villages in the region the MdS is held, his way of giving back.

What began as one man’s multi-day, algerian expedition has now blossomed into a race format so popular that dozens of stage races host thousands of runners around the world each year.

“I just wanted people to be able to chase their sense of adventure, and am elated to see more races providing venues to do this.” He pauses reflectively, concluding, “The desert called to me. What can I say? I knew it would call to others.”

Timeline

— 1984 > Patrick Bauer hikes 350 kilometers (almost solo) in the Algerian Sahara. During the journey, he invents the stage-racing idea.

— 1986 > Bauer directs the first Marathon des Sables (MdS).

— 1997 > A Moroccan, Lahcen Ahansal, wins the MdS for the first time. This draws interest in the race from in-country runners, and now elite Moroccans compete each year.

— 1999 > Bauer implements a roving field hospital at the MdS that has since been credited with saving multiple lives.

— 2005 > 777 runners begin the MdS.

— 2009 > Record-level rains flood the Sahara Desert. Bauer makes adaptations to ensure competitor safety and allow the race to take place.

Bjorklund nears the finish line of the 1981 Pikes Peak Marathon, setting a record that still stands.

Lynn BjorkLund

Would Give Back Her record

When Lynn Bjorklund was a kid, she had no female peers in her Los Alamos, New Mexico, neighborhood. She instead played with her older brothers and their friends. “I was littler and slower, always sprinting to keep up,” she says. When she was about 12, Bjorklund’s brothers joined the high- school cross-country team and their playtime pursuits homed in on running, “We’d run for hours on our local trails.”

Though the 55-year-old blazed women’s history all over tracks, roads and trails in the 1970s and ’80s, she is probably best known for running 9:08.6 for 3K on the track in high school. This national high-school girls’ record—set in 1975—still stands.

In 1981, Bjorklund made a deep mark on the trail-running world when she flew through Colorado’s Pikes Peak Marathon fast enough to set both ascent and marathon speed records. Her marathon record of 4:15:18 is now 31 years old, and her ascent record of 2:33:31 was only just surpassed at the 2012 Pikes Peak Ascent by Kim Dobson’s 2:24:58.

“I suppose my childhood had all the right factors, including pedestrian play at Los Alamos’ altitude,” explains Bjorklund when asked about what led to her standout day on Pikes. “As for that specific race, it was quite simple. I had trained more than ever.”

“Let me stop here,” she continues, “I trained too much. It made for one exceptional race, but I spiraled into years of chronic overuse injuries that took away my ability to run, as well as the joy of it.” What ailed her after the 1981 Pikes Peak Marathon? “My ankle, my foot, my knee, nothing singular or specific. If I could replay race day, I’d give that record back in exchange for a life of healthy running. It wasn’t worth it.”

Despite this challenging historical relationship with trail running, Bjorklund remains enamored with the sport. “My body disallows every-day running, but I mix in other sports so that I can be as active as I want. I am fortunate that i can still participate in the occasional shorter-distance trail race.” This fall, she placed second at New Mexico’s Pajarito Trail Fest 15-miler. “I’ve fallen in love with triathlon, cross-country skiing, hiking and backpacking over the years. But if I could run more, it’s perhaps all I would do.”

Though her work took her out of her hometown for a while, she’s now back in Los Alamos and working as a Santa Fe national Forest recreation manager. her work days are largely spent in the outdoors, “I help restore and maintain trails and plan events taking place in the forest, such as trail races.”

She’s still a fan of the mountain-running scene, too. Last summer, Bjorklund reached out to congratulate Dobson after her record ascent. Says Dobson, “Lynn is a legend. I began running on Pikes Peak in 2009, and am in perpetual awe of what she did. It’s amazing that the mountain has now connected us.”

Bjorklund offers up advice for female runners who are pushing their training and racing limits, “eat real food, enough of it. rest more. Keep your period. Train under a coach. Don’t betray the long view for a single event. Train and race with enough caution so that you’ll still be healthy in 20 years. Find your worth inside of you, not in something external like a record or someone’s opinion of you.”

Timeline

— 1974 > Lynn Bjorklund wins the USA Track and Field Cross Country Championships for the first of two times.

— 1975 > Bjorklund runs a 9:08.6 for 3K at an international track meet in what’s now the Ukraine. This national high-school girls’ record still stands.

— 1976 > Bjorklund places seventh at the International Association of Athletics Federation World Cross Country Championships.

— 1981 > At age 24, Bjorklund wins the Pikes Peak Marathon in course-record time, also setting the (now-previous) ascent course record in the process.

— 1997 > On a backpacking trip in New Mexico, Bjorklund witnesses a small- plane crash and runs 18 miles to the trailhead to report the emergency. Her swift action is credited as lifesaving to the two injured and burned passengers.

Western states pioneer Gordy Ainsleigh near his Meadow Vista, California home. Photo by Carl Costas

Gordy Ainsleigh

Oddball Inventor Of 100-MIle trail races

The dude who first raced 100 miles through hill, dale, heat and canyon is about as offbeat as that original run. If you’re familiar with the Western States 100- Mile Endurance Run (WS 100), you’ve likely glimpsed the race’s first participant, the near-naked, hair-flying, devilish-grinned, 200-pound, perpetually flirting Gordy Ainsleigh.

It’s now an oft-told story: in the summer of 1974, Ainsleigh ran The Tevis Cup, a 100- mile horse race across the Sierra Nevada of California, without a horse. He completed the distance in less than 24 hours, proving that 100-mile races were possible on foot, a concept that has wildly evolved. In 2012, 95 100-mile races took place in just the United States, including the 39th WS 100. Ainsleigh blames a woman for his decision to run The evis Cup. “The year before, I gave my girlfriend the horse I’d previously used to race the Cup. I thought she and I would be together forever and that I’d still be able to race with the horse.” That woman eventually left him with the horse in tow. It was about the same time that The Tevis Cup’s administration asked Ainsleigh if he wanted to run the race as a pedestrian, “They noticed my previous strategy when racing with a horse to run with it instead of riding it for portions of the race.” The stars aligned for the strange man’s August 3, 1974, 100-mile, on-foot foray.

And, when Ainsleigh talks about the hardest part of that first 100-mile run, he says a woman saved him. “My friend Diane [Marquard] was at Devil’s Thumb. I was in pain, and I’d just seen someone’s horse dying from overexertion in such heat. I thought I was headed for the same fate, but she gave me salt, water and a leg massage until I got turned on enough to forget about dying.” Ainsleigh is so emotionally attached the WS 100 that he starts it every year, no matter if he thinks he can finish it. “i treasure the epic-ness of this race. it’s far; it’s hot; and, now, it’s highly competitive. i can’t wait to stand at the starting line. But when I’m there these days, i feel equal parts excitement and dread. I’m old, and it’s been a while since i finished under 24 hours. Thirty hours is a stretch. But i don’t stand on the sidelines well.I’m a doer.”

WS 100 race rirector Craig Thornley grew up near the course. Despite always knowing who Ainsleigh was, Thornley, who was named RD in January 2012, only recently got to know him personally. “He’s got a spirit that is tangible when you see it. He beats to the rhythm

of us own drum. he’s an enigma.”

Ainsleigh has strong opinions on the future of this now-hyper-popular race, which had almost 2300 applicants enter its 2013 lottery. “I want everyone to be able to run it, if they want to,” he says, although he has no decision-making power. “The course needs to change just a little, so we avoid the wilderness area that limits the race’s number of entrants. if you want to come out here and suffer and ponder death and find life, you should be able to.”

Ainsleigh still keeps ladies and the race in close relationship, too. At modern WS 100s, he’s typically paced and crewed by a bevy of beautiful women. “They’re very motivating, you agree? My wife doesn’t seem to mind.” He laughs and continues, “The older i get the more I need those pretty women to run with. I didn’t expect to live to be this old and I’m a little mentally unprepared for it. I’m pretty good at keeping myself healthy. I don’t eat white-flour products or sugar, and I do drink a little wine.”

The 65-year-old does enjoy a vibrant life beyond the race. he’s passionate about his chiropractic practice, natural health, climbing and politics. For instance, his scantily clad approach to spending time outdoors is based on reason, “I once co-published a paper about the health benefits of some sun exposure. i try to get a little sun every day.” On climbing, he says, “I love it. But this year I hurt my foot while climbing, and I haven’t been able to run much. Pisses me off, one hobby getting in the way of another.” We have a feeling, though, that we’ll see him at the starting line in June.

Timeline

— Early-to-mid 1960s > Ainsleigh runs on the Colfax High School track team in California, where he sets a then-school record in the two-mile race.

— 1971 >. Ainsleigh finishes The Tevis Cup, a 100-mile horse race, for the first time, on horseback in 19:37.

— 1974 > At age 27, Ainsleigh completes The Tevis Cup on foot in 23:42.

— 2007 > Ainsleigh finishes the Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run (WS 100) for the 22nd time, his most recent official finish, in 29:30.

— 2010 > Ainsleigh finishes the WS 100 but misses the 30-hour cutoff by minutes.

Naylor and one of his beloved Border Collies running in the rugged fells near his home.

In the UK Fells with

Joss Naylor

They say that 76-year-old Joss Naylor is still a sight to behold as he runs England’s Lake District fells, his lanky body bending easily and his arms outstretched, bird-like, as he moves over the technical terrain. “He keeps a steely glint in His eye and His muscles are like High-tension metal stretched to their limit,” says Keith Richardson, who wrote Joss: the life and times of the legendary lake district fell runner and shepherd Joss Naylor (www.rivergretawriter.co.uk). “He is as light as a kite but also hard as nails.” Almost any British sports fan would agree: Naylor is also an icon. The runner has spent most of his adult life bagging England’s fells, usually in record time … That is, when he’s not farming sheep.

In a valley called Wasdale, in the Lake District’s rural Cumbria county, Naylor lives in a 400-ish-year-old farmhouse on about 150 acres. The house and a small collection of outbuildings stand in a cluster on rolling hills between the valley’s lake and steep fells dividing it from the next valley. His fields are cordoned off by rock walls—some as old as his house and some he has handmade—and he uses a posse of friendly Border Collies to work the sheep.

While most people come to this neck of the woods for summer vacation, this has always been Naylor’s home and playground. Almost every day when the farm work is done, naylor takes his dogs and heads onto the fells. Says Richardson, “There is nothing Joss likes more than to be running on the fells with his dogs.”

Naylor’s life has been vibrantly punctuated by marriage to his wife, Mary, and their raising of three children. These days, Naylor also escapes to Spain during Wasdale’s dark, snowy winters.

Naylor experienced major back and knee injuries during the first two decades of his life. residual inflexibility and pain from those injuries, however, didn’t stop him from embracing the lake District’s traditional culture of outdoor work and recreation. and, in his mid-20s, Naylor learned about the beauty of moving fast through the landscape when he entered a fell race near his family’s home. Though Naylor did enter (and dominate) some competitions, he evolved a preference for running that most resembled that of the Bob graham round.

In 1932, Bob graham, a guesthouse owner in Keswick, a town located in the northern lake District, summited 42 local peaks in under 24 hours. When graham made his “rounds,” a route that was between 63 and 65 miles with roughly 27,000 feet of elevation gain, this speed approach to fell travel had already been popular for at least three quarters of a century. graham set a high mark, though, that wouldn’t be repeated until 1960.

In the 1970s, Naylor bettered the 24-hour record on three occasions, the best being in 1975 when he topped 72 peaks in 23 hours 11 minutes on a route he says was around 100 miles long with 38,000 feet of elevation gain (Naylor’s record has twice been surpassed, most recently in 1997 by Mark Hartell, who nabbed 77 peaks in 23 hours 47 minutes). Naylor’s solo fell efforts go on, including running 60 fells in about 36 hours when he was 60 and 70 fells in less than a day when he was 70. and last spring, as if in complete defiance of age, Naylor ran the boundaries of Wasdale, which involved close to 35 miles and 11,000 feet of climbing, in just under 10 hours.

“Don’t be fooled by the man who didn’t race much,” says Richardson. “Joss was and is hyper-competitive, but mostly with himself. He never gives in.

“People love what Joss represents as a runner, a cumbrian character and someone who loves his homeland more than most else.”

Timeline

— 1936 >Joss Naylor is born in Wasdale Head, England.

— 1940s >. Naylor experiences a back injury that debilitates him for several years.

— 1954 > Naylor has surgery for an unknown knee injury. — 1958 > Two discs are surgically removed from Naylor’s back in an attempt to relieve pain caused by a childhood injury.

— 1961 > Naylor participates in his first fell race, which takes place near Wasdale Head.

— 1971 > Naylor runs 61 Lake District Peaks in 23:37, breaking the previous Lake District 24-Hour Fell Record by one peak.

— 1972 > Naylor breaks his own Lake District 24-Hour Fell Record from the previous year, bagging 63 peaks in 23:35.

Naylor and one of his beloved Border Collies (left); and on a run in the rugged fells near his home.

— 1975 > Naylor runs 72 peaks in 23:11, resetting his own Lake District 24-Hour Fell Record by nine peaks (the record has since been twice re-broken). For this nine-peak jump in the record, which is often cited as fell running’s greatest achievement, he was made Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.

— 1986 > Fifty-year-old Naylor sets the still-standing record for running the Wainwrights, a set of 214 Lake District peaks, at 7 days 1 hour 25 minutes. His route was 391 miles long and contained 121,000 feet of ascent.

— 2012 > At 76, Naylor is chosen by the London Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games to be an Olympic Torchbearer at the 2012 Summer Olympics for inspiring generations of runners.

Kilian Jornet

Goes Faster and Lighter

Last September, Catalan Kilian Jornet traversed 15,781-foot Mont Blanc, western Europe’s tallest mountain, from downtown Courmayeur, Italy, to downtown Chamonix, France, in 8 hours 42 minutes 57 seconds. The route, which he created to connect the two towns with a Mont Blanc traverse, was just under 26 miles long and had 12,595 feet of ascent. He used Italy’s airy and altitudinal— but technically moderate—Innominata Ridge to access the summit, which includes a sometimes-hairy (though Jornet said it was fairly safe during his speed outing) crossing of the crevassed Brouillard Glacier.

Says professional ultrarunner and recreational climber Dakota Jones, who reconnoitered the route with Jornet a week before his speed attempt, “The route has insane exposure. But, technically speaking, ‘moderate’ is right. We only roped up on the glacier and one other section.”

Jornet spent 90 minutes approaching the Innominata Ridge route proper and roughly 2 hours 25 minutes descending the mountain in a combination of road running, trail running, snow running, glacier running and scrambling. He says this kind of running is his favorite: “I like the act of running, the moving, the breathing, the wind on my face. But if I’m not going somewhere—to a summit or over a whole mountain—then there is less meaning to the movement.”

At just 25 years old, Jornet is the king of any sport he plays, making him a quite- young legend. He wins almost every competition he enters in ski mountaineering, mountain running and ultramarathoning. But he also rebuffs the concept of sports with strict, differentiating definitions. “If i do just one sport on the mountain, I will only see a part of it. I want to experience the whole mountain, so I use whatever techniques I need.” Jornet approaches mountain projects with an ethic not unlike the way he races. “I go fast. I carry little.”

His fundamental take on mountain travel is not new— the age-old sport of mountaineering has continually evolved to faster and lighter records. Dani Arnold’s work of the Eiger north face and Ueli Steck’s attack on Shishapangma’s southwest face are recent examples of fast-and- light efforts on technically difficult routes.

But many mountaineers think Jornet is going faster and lighter than almost anyone previously. And he has plans to pioneer his style beyond the Graian alps in his Summits of My Life project. The speed records for Mount Elbrus, the Matterhorn, Aconcagua, Denali and Everest are on his hit list between now and 2015. “If he can pull off this proj- ect,” says Jones, trailing off, searching for an apt descriptor for the impact it would have on speed mountaineering. “Well, it would be a really big deal.”

Says Jornet, “I carry less equipment than many. But, when I move fast, I spend less time exposed to weather, avalanche areas, the possibility of rockfall.” His history of multi-season, multi-sport alpine play that began when he was a baby has yielded a robust skill set, and he possesses a training drive like few other humans. But mountaineering possesses inherent risk, and Jornet well knows that no style is immune to it. During a June 2012 speed project on Mont Blanc, he lost his friend Stephane Brosse when a cornice collapsed.

“You have to approach the mountain with the style that makes you feel most secure,” he says. “This shows the mountain the greatest respect. I am lucky that my style also makes me feel free, the same feeling as flying.”

Timeline

— 1987 > Kilian Jornet is born.

— 2004 > Jornet wins his first international ski-mountaineering competition when he becomes the International Ski Mountaineering Federation Vertical Race World Champion in the Cadet (junior) division.

— 2006 > Jornet undergoes two reparative surgeries for a patella fracture that occurred when he fell on the street while walking home from school.

— 2008 > Jornet wins the Alps’ Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc for the first of three times.

— 2009 > Jornet sets the supported 165-mile Tahoe Rim Trail speed record at 38 hours 32 minutes.

— 2010 > Jornet sets the Mount Kilimanjaro speed record at 7 hours 14 minutes via a 32.9-mile round- trip route to and from the 19,340-foot summit.

— 2011 > Jornet is crowned the International Ski Mountaineering Federation Overall World Champion (he again won the title in 2012).

— 2011 > Jornet wins the Western States 100- Mile Endurance Run in 15:34:24, the sixth-fastest finishing time ever.

— 2012 > Jornet captures both the International Skyrunning Federation’s World Series and Ultra Series champion titles.

Smead nearing the finish line at 14,050 feet during the 2011 Pikes Peak Ascent.

Chuck Smead

Takes on the Euros

“In those days, I was getting a course record every time I raced.” Colorado’s Chuck Smead is not afraid to tell you how it is. In reference to his 1970s dominance of American running, he isn’t exaggerating, either.

Smead, now 61, was the 1972 and 1973 winner of the Pikes Peak Marathon and the 1974 and 1976 winner of the Pikes Peak Ascent. His 1976 ascent win included a course-record time of 2:05:22—which stood until 1993 when Matt Carpenter ran 2:01:06. He placed second in the marathon at the 1975 Pan American Games in Mexico City, located at 7900 feet altitude, by running a 2:25:32 and 29 seconds back from the winner. And, in 1976, he won the inaugural Amateur Athletic Union of the United States, Inc. 50K National Championship; his obscenely fast 2:50:46 was an asterisked American record for years due to different measurement standards.

In 1977, Smead became the first fast American trail runner to take his talents across the pond. That year, he won Switzerland’s Sierre-Zinal, perhaps the most respected mountain-running race on Earth. Smead raced Sierre-Zinal four more times in the late ’70s and early ’80s, bringing with him other fast dudes from the United States like Pablo Vigil and Dave Casillas. This troupe together started a trend of Americans racing in Europe that has grown to what’s now a veritable exodus each summer.

“Chuck was the Jack Kerouac of united states mountain running. he was Just a vagabond in Europe, but such a fast one,” recalls Vigil, the Colorado mountain runner who won Sierre-Zinal four consecutive times between 1979 and 1982. “He blazed the way for me to go for the first time in 1979. Now, I’ve traveled to and raced in Switzerland so many times that it’s my home away from home.”

“Seven or eight summers total I raced in Europe,” remembers Smead. “Each time, I stayed a couple weeks—maybe a month—and ran as many mountain races as I could.” Why exactly did Smead cross the Euro mountain-running threshold when no one else was?

“Easy answer, money. I was a poor teacher with a mortgage payment, a wife and young kids. making money on running in America made for a scrappy existence.” he continues, “I could go to Europe for a month, all expenses paid [by race organizers], and make $4000. Back then, that was a ton of money.”

Smead has never stopped racing, though he’s now converted to chasing age-group course records at prestigious races. “Let me tell you the truth. I wake up and think, ‘My competition is running today, so I have to run, too.’ I enter races now because they keep me from being lazy. I’m old, but I want to live a lot longer. This crap keeps me healthy.”

Smead and his wife, Carol, live on 10 flatland acres outside of Mosca, Colorado, which is effectively the middle of nowhere. They have three grown boys and the couple is, according to Smead, semi-retired. “I’m a stamp dealer and Carol’s a tutor. We don’t really need our jobs, but be want them. Old people need things to do, you know.” Smead runs most days, “I do lots of speed workouts, not much mileage but almost all of it fast on the dirt roads out here. I live in the death zone, at 7600 feet. Living at this altitude is hard on the body. No two-a-days up here.” On easy days, Smead swims and pool runs at a nearby hot-springs pool.

Turns out, Smead’s still better than almost all of his competition, too. Last fall, he championed the 60-64 age group at the USA masters 5K cross country championships with a 19:42, 32 seconds faster than everyone else. In 2011, he won and set a course record in the men’s 60-64 age group at the Pikes Peak ascent with a 2:58:47.

“I’m not through with the Mount Washington road race. I tried for my age-group win there in 2012, and failed. I’m going back.” Smead is also thinking about another shot at Sierre-Zinal this summer, “Europeans aren’t as into age-group records as Americans are, but I can’t help wanting to go after a record there, too.” Clearly, Smead’s got some more pioneering to do.

Timeline

— 1972 > Chuck Smead wins the Pikes Peak Marathon for the first of two times.

— 1973 > Smead wins the NCAA Division II Six-Mile Championship for the first of two times while in college at Humboldt State University.

— 1974 > Smead wins the Pikes Peak Ascent for the first of two times (In 1976, he would win and set an ascent course record of 2:05:22, which stood until the reign of Matt Carpenter began in the 1990s).

— 1975 > At the Pan American Games in Mexico City, Smead runs to a silver medal in the marathon. Smead nearing the finish line at 14,050 feet during the 2011 Pikes Peak Ascent.

— 1977 > Smead wins arguably the most prestigious mountain-running race in the world, Switzerland’s Sierre- Zinal. He would race it four more times in the coming years, never placing out of the top five.

— 2008 > Smead sets a men’s 55-59 age-group record at the Mount Washington Road Race with a 1:17:15.7.

— 2011 > Smead sets the men’s 60-64 age-group record at the Pike’s Peak Ascent with a 2:58:47.

— 2012 > Smead wins the men’s 60-64 age group at the USA Masters 5K Cross Country Championships with a 19:42. .