Indigenous Runner and Artist Yatika Fields Creates Beauty at the Western States 100

(Photo: Photo: Elmer Ferro for Strava)

Yatika Starr Fields was exhausted with dead legs and blistered feet when he cracked open a Dr. Pepper and slumped back into a camping chair on the turf infield of the Placer High School track.

The accomplished 41-year-old ultrarunner from Tulsa, Oklahoma, completed the Western States 100 in his first attempt, covering the course in 26 hours, 28 minutes and 55 seconds.

“I only drink soda during ultras,” Fields said with as much of a smile as he could. “I love Dr. Pepper when I finish an ultra. This actually helps me finish, knowing that I get to have it at the end.”

What really helped Fields finish, he says, was the ability to represent the Native American people who once inhabited the land of the Western States course. He was running for Rising Hearts, an Indigenous-led grassroots advocacy organization that works to elevate the voices of Native peoples and cultivate community for racial, social, economic, and environmental justice.

RELATED: Indigenous Athletes are Running For Justice

Specifically, Fields was running as part of the Rising Hearts’ Running on Native Lands Initiative to bring attention to the Washoe and Nisenan people, who have inhabited the land of the Western States 100 course for more than 6,000 years, and to develop the first land acknowledgement with the race organization this year, publicly presented at the training camp weekend and before the start of the race.

Although Fields suffered from cramping legs early in the race and struggled to run downhill during the second half — both of which contributed to him missing his goal of finishing in under 24 hours — he said he persevered because of the bigger mission at stake.

“I was running for them. I’m running for a lot of Natives, and I felt that out there,” he said. “We’re mediators, we bridge conversations, and it takes a lot of people to do that. It takes effort and action, and my run was part of that action. That’s what helped me finish, to be honest. I broke down crying out there because I could feel it. I was in pain, but I got it done with that in mind.”

Of the 305 finishers in this year’s race, 204 finished between 24 hours and the 30-hour cutoff to claim a bronze finisher’s belt buckle. The many hours leading up to Golden Hour — the closing 60 minutes before the cutoff time — is a stunning testament to the effort of middle-of-the-pack runners who step away from everyday life and full-time jobs to give uncommon efforts to grind to achieve the extraordinary feat of finishing the race.

“We’re mediators, we bridge conversations, and it takes a lot of people to do that. It takes effort and action, and my run was part of that action. That’s what helped me finish, to be honest.”

Like the other finishers sprawled out around him, Fields is anything but common. A native of Oklahoma with Cherokee, Muscogee, and Osage roots, his race résumé also includes finishes at the Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc TDS, Ouray 100-miler, and Ultra Caballo Blanco Copper Canyon 50-miler. He’s most well-known for being an accomplished painter, muralist, and street artist known for using vibrant colors to authentically celebrate and honor Indigenous people. (In October 2021, Fields helped paint a mural for the Boston Athletic Association to celebrate Indigenous People’s Day.)

Although he discovered running later in life, art was always in his blood and now the two passions are intersecting. As the son of two Native artists, he became fascinated with painting as a young teenager, always influenced by his family heritage and a desire to present a deeper, more authentic understanding of Indigenous cultures that have been misrepresented. He has painted numerous murals on Indigenous lands, but he’s also contributed to art installations and had his work on display around the world.

The kaleidoscopic imagery depicted in a lot of his work has been interpreted as portraying diversity, spiritual symbolism, and forward progression of Indigenous cultures. Since he started running, he’s also tried to connect with some of those same qualities out on the trails.

“Movement through running to me is a reminder of who we are and our true inherent spirits,” he told Native News Online. “I grew up attending our Osage dances and ceremonies in Oklahoma at an early age, where I feel that’s where the first connections of prayer and movement came to be present. There’s a similar dynamic in running for me that ties and intersects with that of prayer in the ceremony. It is a form of ceremony for me.”

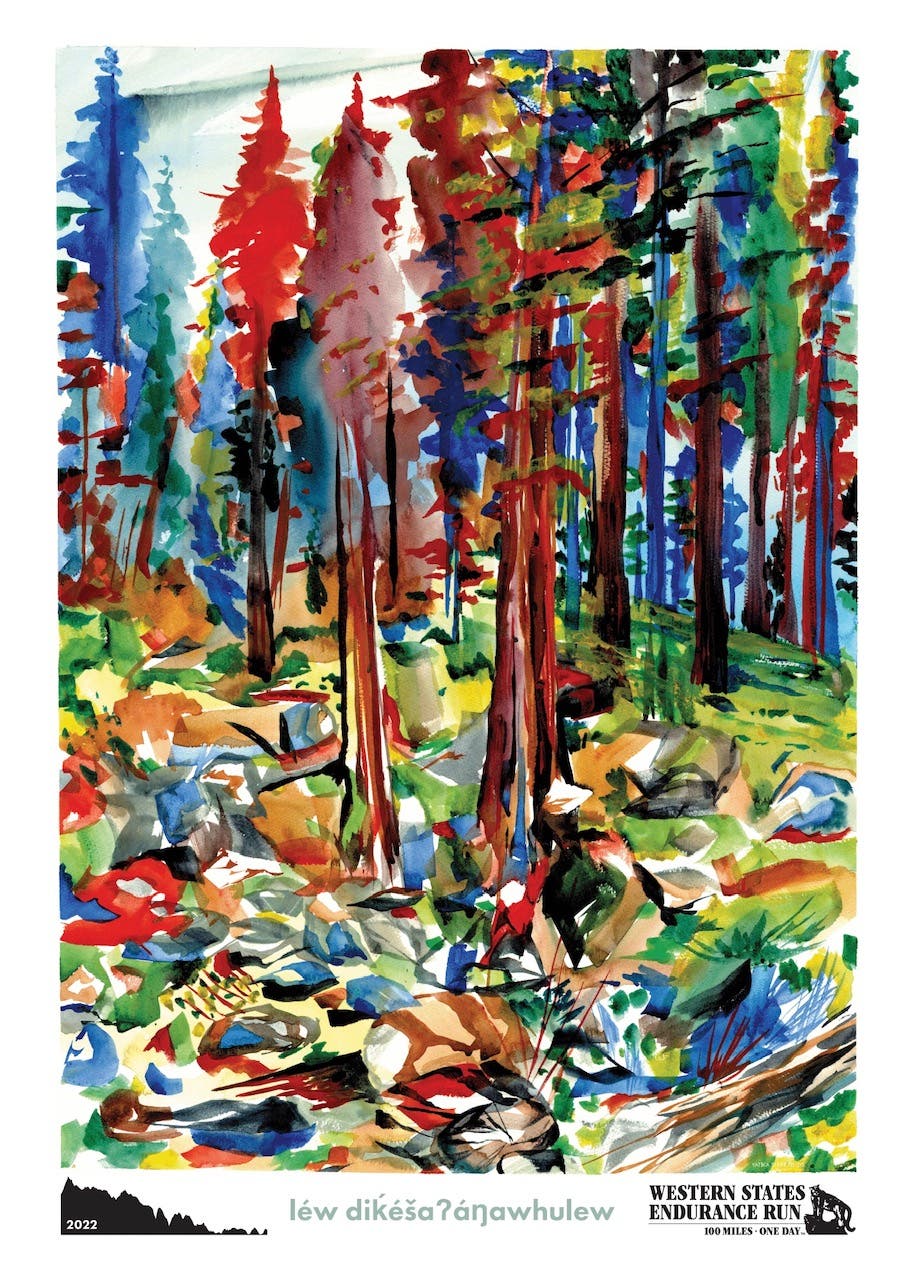

While attending the Western States training camp in late May, Fields covered about 70 miles of the course, but he also took time to paint four pieces of art to honor the Washoe, one of which became the first-ever official poster of the race. (The painting depicts a forest portrayed in brilliant colors with a Washoe phrase that translates to: “Together we will live-breath good.”) Proceeds of the sale of the posters will support the Washoe community and Western States Endurance Run Foundation.

“These are baby steps, but these are steps in the right direction,” said Rising Hearts founder Jordan Marie Daniel (Lakota), who was chronicling Fields’ race with a video crew for a forthcoming film. “We advocate for races to donate a part of their proceeds or donate comped entries (to Native people) and other ways to develop meaningful ways to give back to the community from the land we are running and recreating on. That’s what brought us all together. It was an amazing opportunity, and we had a lot of firsts for the Western States 100.”

RELATED: Recap: Western States 100

During the race, Fields was paced by Native runners Craig Curley (Navajo), a professional marathoner, and ultrarunners Brian Williams (Cherokee) and Dr. Lydia Jennings (Huichol and Pascua Yaqui), who was featured in Patagonia’s film Run to be Visible.

Fields was sponsored by GU, which gave him its sponsor entry as a purposeful way to help expand the diversity of the race and help connect the race to the original people of the area.

“We wanted to make sure that we were unlocking an opportunity for something much deeper than a runner finishing on the podium … for running and racing with a purpose,” says Celia Santi, GU’s Director of Community and Purpose. “We talk a lot about protecting the places we play, but we don’t do a lot to step back and think about, ‘What is this place we are playing on?’ Rising Hearts promotes the idea of ‘running with the land’ and that gives a deeper sense of purpose when we step out on the trails.”

Herman Fillmore (Washoe), culture and language resources director for the tribe, delivered the land acknowledgment prior to the race.

“While the history of colonization has not been kind to Indigenous people, it is our responsibility today to create a better future, as we all face the harsh realities of climate change through increased wildfires and extended drought that are now common in this region. So, as we prepare for the Western State Endurance Run, let us both acknowledge the original stewards of this place, the Washoe [Wašišiw or Wa She Shu], and let us all think of the ways in which we can, through our daily lives, support Indigenous peoples and be better stewards of this land that we all enjoy so much.”

The Western States race organization has said it is interested in working with the Washoe people in new ways in the future.

“We feel it is very important to have this land acknowledgment take place. We see this as a first step in what we hope is an ongoing and developing relationship with local Indigenous groups who inhabited for thousands of years Olympic Valley and the rest of the land where the Western States trail traverses,” says Diana Fitzpatrick, president of the Western States Endurance Run’s board of directors. “We want to honor and respect their role as the original stewards of the land and their continuing presence and importance today. This is an educational and important moment for us all, and we feel extremely honored to have Herman share his words with us.”