An Athlete's Guide To Environmentally Friendly Eating

The science behind food’s climate footprint can feel confusing, and the problem of climate change overwhelming. But, taking just a few simple steps to alter your eating habits can have a big impact. Roughly one-third of global greenhouse gas emissions come from food production, and about half of that comes from animal agriculture. Food production also taps about 70 percent of usable freshwater and occupies 40 percent of global land.

Food production is the largest factor threatening species with extinction, according to a 2017 study published in the journal Nature Communications, contributing to deforestation, desertification, eutrophication (an excess of nutrients in water due to runoff), coastal damage and degradation of reefs and marine ecosystems. Agriculture isn’t just a driver of climate change, but also a victim of its shifting conditions as the climate grows less stable and increasingly unpredictable.

As Jonathan Safran Foer wrote in his book, We Are The Weather, “Changing how we eat will not be enough, on its own, to save the planet, but we cannot save the planet without changing how we eat.”

While global food systems as they exist may not be sustainable, there is hope. Because three times a day (or more, athletes are hungry!), we trail runners can rethink this relationship to the planet, starting with what’s on your plate.

Experts have identified two fairly simple actions as being some of the most impactful actions individuals can take. Minimizing food waste, and reducing consumption of animal products are healthy and cost-effective measures accessible to most trail runners.

“The good news is that a lot of things that are good for the planet are good for athletes too,” says Kylee Van Horn, a Registered Dietitian Nutritionist who specializes in working with endurance athletes. Just eating what we purchase at the grocery store is a great place to start.

Waste Not

According to the World Resources Institute, if food waste was a country, it would be the third-largest emitter of green house gasses behind China and the U.S. Another study by Project Drawdown, a multidisciplinary coalition of experts on climate-change solutions, ranks food-waste reduction as the single most impactful climate action we can undertake (assuming warming of 2 degrees celsius), potentially eliminating 70 gigatons of carbon emissions in the next 30 years (one gigaton is equivalent to a billion metric tons.) Some studies show that as much as 11 percent of greenhouse gas emissions could be eliminated if food waste was brought to zero.

In the U.S., according to the National Resources Defense Council, upwards of 40 percent of food produced each year is wasted. While some food is wasted as part of agricultural processes and throughout the supply chain, consumers actually are responsible for the majority of food waste. An estimated 28 percent of the planet’s agricultural land is used to grow food that ends up in the garbage. Food waste is the single largest solid-waste component of America’s landfills—an estimated 80 billion pounds—and emissions from it are equivalent to the greenhouse-gas output of 33 million cars. This is an environmental and food justice disaster.

“Everyone can minimize the amount of food they waste,” says Emily Olsen, a trail runner and Director of the Cloud City Conservation Center, an environmental and food-justice non-profit based in Leadville, Colorado. “If you want to make a difference at the intersection of climate and social justice, just eating the food we buy is it.”

Where’s The Beef?

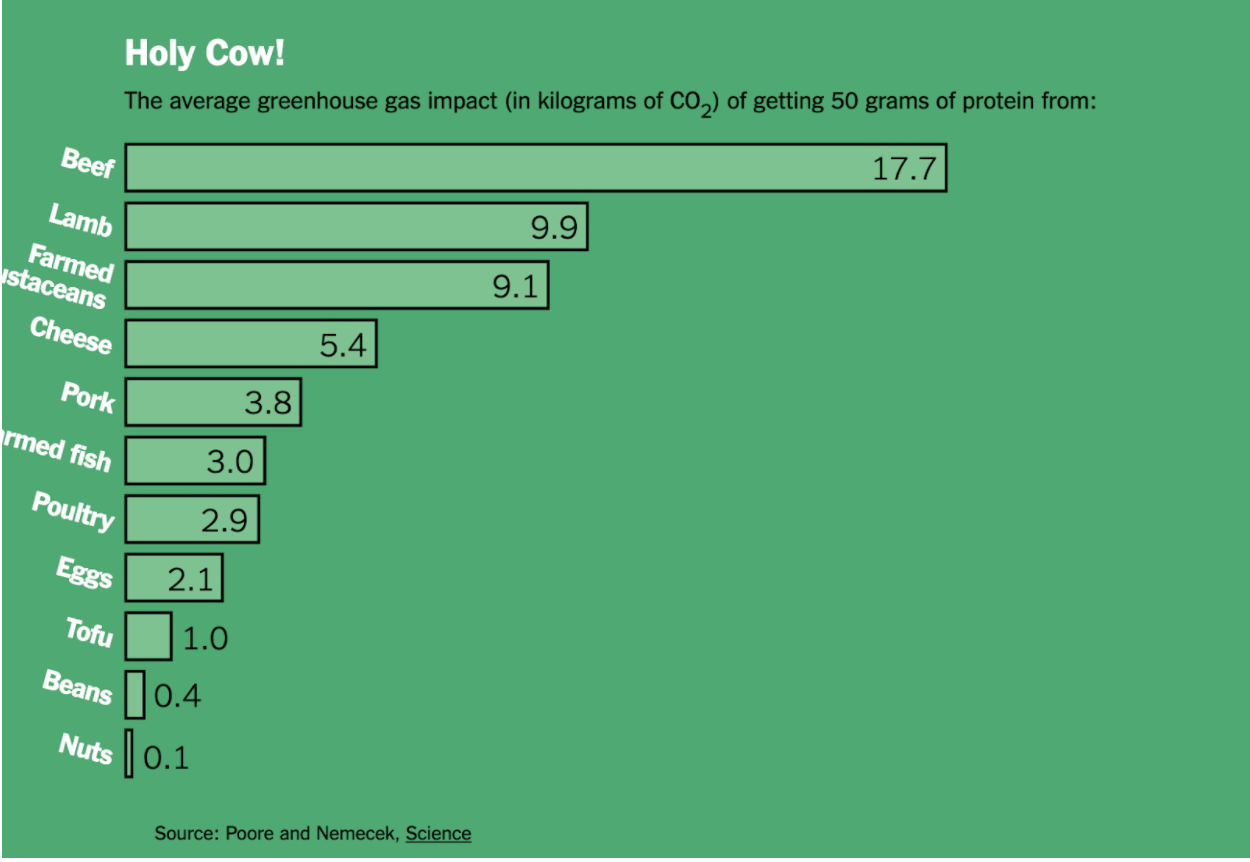

A study at the World Resources Institute (WRI) calculated the greenhouse gas emission associated with producing a gram of edible protein of various foods. Foods like beans, fish, nuts and eggs have the lowest impact. Poultry, pork, milk and cheese have medium-size impacts. Far and away the biggest impacts (just in terms of greenhouse gas emissions—we’re not even accounting for habitat loss, land use or other external costs) were associated with beef, lamb and goat. According to the WRI, the planetary impact of Americans’ meat and dairy consumption accounts for nearly 90 percent of all the land used to produce food, and 85 percent of diet-related greenhouse gas emissions.

The average American eats about 185 pounds of meat a year, which is about eight ounces per day. But, USDA’s 2020 dietary guidelines recommend under half that—3.7 ounces—which comes out to around 84 pounds per year. Eating the recommended amount would mean halving current meat consumption.

“Reducing meat consumption reduces both our carbon emissions and our agricultural footprint,” says Newton. According to a 2016 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, projected global greenhouse emissions could be reduced as much as 70 percent if everyone on earth adopted a vegan diet and 63 percent for a vegetarian diet. “From purely an environmental perspective (i.e., ignoring human health and animal welfare for a minute) most of the problem could be solved without anyone needing to become vegan. Rather, a dramatic reduction in meat consumption would suffice,” says Newton.

Try eating vegan before dinner, and making meat a treat rather than a dietary default. If living without burgers or nachos feels like too big an ask, let yourself have them on special occasions. Enough people making a lot of imperfect decisions and committing to action will have more impact than throwing up your hands at the thought of never eating another cheesesteak. According to a 2015 study by the journal Frontiers in Nutrition, a diet that is vegetarian five days a week and includes meat just two days a week would reduce greenhouse-gas emissions and water and land use by about 45 percent. Eating grass-fed, free-range beef doesn’t let you off the hook either. Meat is still a heavy emitter, no matter how it’s raised.

“Rather than moving immediately from a meat-heavy diet to being vegetarian, try to make small, sustainable changes so that they stick,” says Van Horn. She recommends runners who want to reduce their meat consumption start with eliminating meat at one or two meals a day, rather than going, excuse the pun, whole hog right away.

For athletes concerned about getting enough protein, Van Horn is a huge fan of lentils, which contain twice the protein of most beans per serving. “It’s all about balance,” says Van Horn. Protein recommendations for athletes range from 98 grams of protein a day for casual competitors to 176 grams for serious endurance athletes, depending on weight.

“You can still get plenty of protein while minimizing meat,” says Van Horn. Beans, while less protein-packed than lentils still pack a punch, depending on the variety. Soybeans, split peas and white beans are some of the highest in protein per serving.

Like any trail run, climate action starts with a lot of small steps. Committing to reducing food waste where you can, and cutting out red meat while reducing animal products are the most impactful climate choices an individual can make. A few simple adjustments can go a long way. Emphasize plant-based proteins. Stop wasting food. Get creative in the kitchen. Stop worrying about having the “perfect” diet. You can still eat for performance while minimizing your carbon footprint.

“Your health is linked to the health of your neigbhors, your community and your planet. And that’s powerful,” says Olsen.

Saving the planet begins at breakfast. Let’s do this.