A Run To Save The Boundary Waters

Photos by Brendan Davis

“Alex, is this safe?”

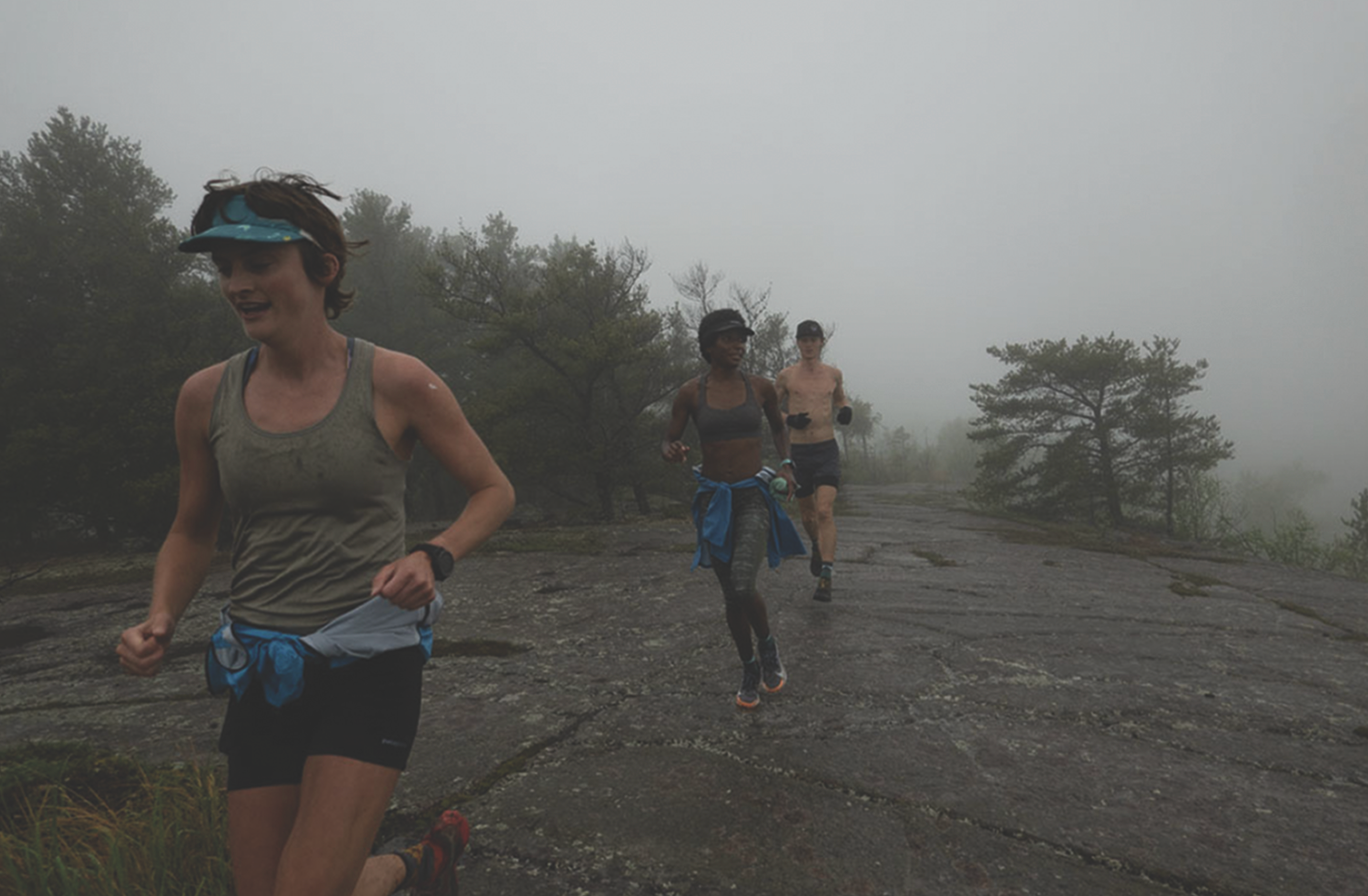

Clare Gallagher wondered aloud, a question that couldn’t possibly have a satisfactory answer. We were at mile 45 of an epic run through the Wilderness with 11 miles to go before we could reach our crew at the first road crossing in 40 miles. Temps had plummeted to near 40 degrees, rain cascaded down and lightning was all around us. “Yes…no…we just need to keep moving” is all I could muster while trying to keep my shivering voice stable for a moment. There wasn’t any other option.

At the Boundary

Tucked away in northeastern Minnesota on traditionally Anishinaabe-Ojibwe-Chippewa lands within what is now known as the Superior National Forest is a remote gem known mostly as a paddler’s paradise. The Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness (commonly called the Boundary Waters) is America’s most visited federally designated Wilderness, with over 155,000 visitors each year. Adventurers from across the country come here each year for the world-renowned backcountry canoeing and fishing, and to appreciate some of the darkest skies on the continent.

A whopping 1.1-million-acre landscape (or waterscape), the Boundary Waters features more than 1,100 lakes all interconnected by rivers, streams, bogs, marshes and other wetlands. It is one of the last places on earth where the water

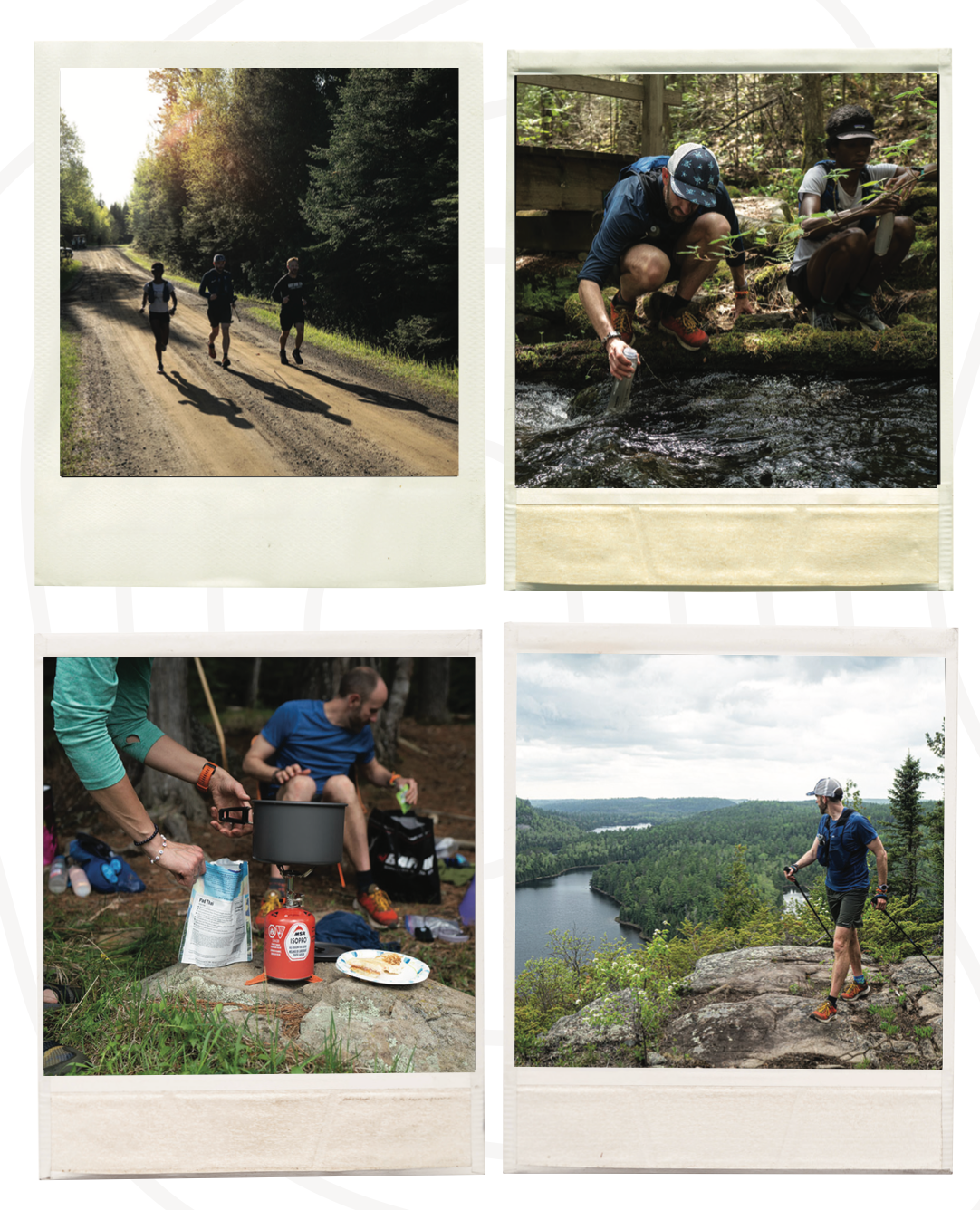

is so pure you can drink straight from the lakes.

The waters and lands are typically traversed via canoeing and portaging, i.e. carrying everything on your back including the canoe flipped upside down on your shoulders, over paths, or “portages”—many, if not most of which, are the same paths Indigenous people have used for hundreds of years.

This is canoe country—which is why I decided to run across it.

RELATED: Laura Cortez Builds Community On And Off The Trails

Land Legs

I am the government relations director for the Campaign to Save the Boundary Waters—a nationwide coalition of over 400 businesses, organizations and constituency groups working together to protect this one-of-a-kind landscape from proposed sulfide-ore copper mining. This kind of mining is America’s most toxic industry and is responsible for the most Superfund sites in the country.

The watersof the Boundary Waters are all interconnected, and a single source of pollution would rapidly spread through the heart of the Wilderness, into Voyageurs National Park, the Canadian Quetico Provincial Park and eventually through Hudson Bay on its way to the Atlantic. Sulfide-ore copper mining has a 100-percent track record of polluting nearby surface or groundwater, and the Boundary WATERS is particularly at risk from the acid mine drainage certain to perpetually leak into the waters of this pristine ecosystem.

I grew up in the Northwoods. As a kid, my grandparents and parents spent the majority of our summer vacation time here, and the Boundary Waters has become our family’s sacred ground. Watching my own children grow up in the wild and seeing the Wilderness newly discovered through their eyes is a joy. They’ve learned how to build fires, navigate, catch dinner and much more.

We have a choice before us. The federal government is considering whether or not to allow Antofagasta, an international mining company from Chile, the ability to open a massive sulfide-mining district at the very doorstep of this wilderness where all pollution would flow through the heart of the over 4-million acres of protected lands and waters. Do we as American citizens and taxpayers want the future of our public lands to be left to the whims of an international mining conglomerate and Superfund sites in its wake? What benefits us when the extracted ore is shipped overseas and the profits land in the bank account of a Chilean billionaire? Or could we leave this corner of the country untouched by the ravages of the modern industrial age for current and future families to enjoy?

Running Waters

In 2019 I started a project to run all of the trails within the Boundary Waters in a public-awareness campaign to bring the issue of sulfide-ore copper mining to the running and specifically trail-running community. We trail runners are a unique breed—we need expanses of relatively untouched land to pursue what most see as an insane hobby. Perhaps because of the intimate relationship we have with the land and surrounding environment, trail runners are increasingly becoming advocates for environmental causes.

RELATED: When Passion Becomes Protection

If I’m not in the Boundary Waters exploring the Wilderness, or at work trying to protect it, I’m usually found out on trail somewhere. The Midwest, admittedly, isn’t the center of the trail-running world like the Mountain West. Minnesota does, however, have the Northwoods, featuring the iconic Superior 100 Fall Trail Races, which include the 10th-oldest 100-miler in the country, a point-to-point race on the Superior Hiking Trail with 21,000 feet of elevation gain—an unrelenting death by a thousand cuts of constant up and down over rocks, roots and boulders.

This trail-running spirit of the Superior 100 can also be found just a bit farther north in the Boundary Waters Wilderness, which is home to more than 250 miles of trails in addition to the almost limitless canoe routes. Typically, the trails are used as multiday hiking and backpacking routes, and all of them are remote, rugged and wild. There are only three human-constructed bridges on any of these trails—the rest are formed from beaver dams or fallen trees. The trails themselves cut through the only section of the Canadian boreal forest in the Lower 48 and are some of the rockiest and rooted trails I’ve ever run on. Oftentimes they are flooded (again the beavers) or blocked by downed trees or are hard to follow as they wind through recent forest fire areas.

Running through the Boundary Waters has only deepened my appreciation and love for this wild place. Alongside eagles soaring at eye level, I’ve stood at the top of 500-foot granite cliffs overlooking the lakes and forests miles into Canada and then run down to cross a river via beaver-dam bridges. I’ve been stared down by moose, startled by black bears and chased by ruffed grouse protecting their chicks. Around a billion mosquitos and deer flies have found a snack from my body. The forest hosts proud stands of old-growth cedars and red and white pines that have been watching over the landscape for 300 years or more. The forest is so alive. And life depends on clean water.

Building Bridges

A couple of years ago, I connected with Clare Gallagher, a Patagonia- and La Sportiva-sponsored runner, the 2019 Western States 100-Mile Endurance Run champion and an environmental activist, at the Outdoor Retailer tradeshow in Denver, and shared my idea to run the Boundary Waters Traverse—a 110-mile route linking the two main trails s through the heart of the Boundary Waters to raise awareness about the copper-sulfide mining threat and, of course, an immense personal challenge. Clare’s activism and passion are electric, and she immediately jumped on board with h this idea. In 2019, seconds after crossing the finish line at Western States after an epic battle to the finish, she shouted, “VOTE FOR THE ARCTIC!”

She was just as game for this adventure.“That is so sick, I’d love to help.”The Border Route Trail (the “BRT”) and the Kekekabic Trail (the “Kek”) together run east to west through the Wilderness with 18,000 feet of elevation gain and loss and they are accessible only by the trail itself or from an occasional portage between lakes. At that time the current FKT on the BRT was more than 24 hours and nobody had established a record of running the Kek. I knew that to be successful this would require some homework, and I put a plan in motion to run each individually that year, and link the two together in 2020.

RELATED: How Trail Runners Can Offset Their Carbon Emissions

On my BRT attempt in 2019, in balmy 93-degree temps, heat exhaustion set in by mile 30, and I was unable to cool off, the mosquitos were relentless, and I couldn’t keep anyfood down. To top it off, I tripped and smashed a toe on a rock around mile 17, which I shrugged off at first. But by the time I was climbing the last main set of switchbacks at mile 45, the pain was unbearable and the opposite leg had lost most function from overcompensating. The wheels had clearly come off. I jumped in a lake to cool off, attempted to get some water and electrolyte mix down and kept going. I ended up DNFing at the first road that crossed the trail around mile 56.

That October 2019, with a healed toe and a Superior 100 under my belt, I took on the 40-mike Kek and finished the run for the first reported FKT.

Finally, in May of 2021, Clare and I were able to conspire on the Boundary Waters Traverse. She was set to support me and also recruited Peyton Thomas, another Patagonia ambassador. Also joining our team was Kyle Pietari, who had four consecutive top-10 finishes at Western States and is a pro bono lawyer on our legal team. The Grand Marais, Minnesota, Jay Arrowsmith-Decoux, Mayor of Grand Marais and a running-store manager Matt Wardhaugh rounded out the runners who agreed to support me on this journey. Also along was photographer Brendan Davis who ran and helped document much of the journey.

With around 90 miles of the route purely within the Wilderness area, I came up with the idea of “paddle-in aid stations” and family, friends and coworkers stepped up to the task, some of them paddling three or more hours and setting up camp overnight to meet us where portages crossed the trail. For logistical purposes, the route was broken into seven segments with six aid stations, three of which were paddle-in aid stations.

Paddling in

Runners and some of our crew camped overnight at the McFarland Lake Campground the night before, which intersects the Traverse at mile 12. During the first segment from the BRT East Trailhead, I was joined by Jay. His energy and quick witted sense of humor were the perfect beginning to the start of the run around 4 a.m.

The sky was just starting to lighten at predawn when we hit the trail to the sounds of my wife, Erica, the kids, Clare and Brendan cheering for the send-off. The 12 miles passed quickly on fairly heavily trafficked trails that were easy to follow and traverse. My fresh legs were cooking along, and we met the crew at our first aid station at the McFarland campground.

RELATED: A Trail Runner’s Guide To Environmental Justice

“Should we emerge from the woods singing ‘Chariots of Fire’ or ‘Oklahoma?’” Jay posited as we neared the end of our segment. It’s funny what you can learn about one another while running through the woods. We pieced together that we ran in the same group of runners during a Spring Superior 50K (where we also watched Coree Woltering pass us by, crushing the field in his trademark Speedo), and we both share a fondness for show tunes.

Jay tapped out, and I headed up the trail with Peyton and Brendan. The weather quickly spiked with the rise of the sun, and soon it was in the 80s and humid. This part of the trail crosses into the Wilderness border with tall stands of red pines and sweeping views out over the Boundary Waters’s lakes and forests. The shade from the trees provided some relief from the heat, though more than once we stopped to dip our hats in the water and fill our flasks.

We made our way to the first paddle-in aid station, where Erica and the kids had escorted Clare out to meet us. After we waived goodbye to Erica, Peyton and the kids, Clare, Brendan and I were off on my favorite segment, but also the toughest of the BRT. This section is characterized by constant climbs and descents, with views into Canada across the boreal forest and lakes stretching to the horizon.

At mile 35, between the heat and my stomach rejecting food, my energy levels dipped. Puke and rally—this is the way of the ultra! Clare forced me to eat an energy gel, which stayed down and was a definite pick-me-up. At the top of the last main climb, Brendan cramped up hard and had to take a break, nursing a double charley horse that literally looked like baseballs throbbing under his skin. The aid station was close, so Clare stayed with him while I ran ahead to get to the Rose Lake aid station with Megan, Ingrid and Cassandra who were all set up and ready. Cassandra took my poles back to Brendan to help him out.

About 15 minutes after I left the aid station, the temps dropped to the low 40s, and the sky opened up and poured on us with lightning all around. It was a fast-moving storm cell, and we could see light behind it on the horizon. Though it rained for only an hour, the foliage was now drenched and kept us soaked through the rest of the night. Hypothermia was a worry, but we kept moving and stayed warm enough. After a couple of water stops and river crossings via logs, we made it to the end of this segment where Erica was waiting at the first road crossing in 40 miles with a warm car and dry clothes. Peyton and I tackled the rest of the BRT together through the night hours, coming to the BRT’s western trailhead just as it was getting light.

Peyton is a wicked smart Ph.D. student out of Wilmington at North Carolina. I was also briefly a Ph.D. student before joining the world of politics, and I listened intently as she described her research. Anything to keep my tired mind out of the pain cave in the dark those last 10 miles of the BRT.

Peyton is a wicked smart Ph.D. student out of Wilmington at North Carolina. I was also briefly a Ph.D. student before joining the world of politics, and I listened intently as she described her research. Anything to keep my tired mind out of the pain cave in the dark those last 10 miles of the BRT.

The next aid station was a welcome respite, with 70 miles and 12K vert on my legs. I hadn’t been able to keep food down for 35 miles and was shivering from being rained and dripped on for the past eight hours. As I sat in a chair with a rubber- ducky blanket wrapped around me, Kyle handed me a piece of gluten-free bread and a cup of broth, coaxing me to down both like a child. “Here comes the choo-choo train,” Kyle e jeered, while the adults all around cheered for every bite.

Here we joined the Kek, which is even more remote than the BRT, though with less dramatic elevation gain. This section crosses the main unit of the Wilderness, and for 40 miles there’s no human infrastructure other than a rickety y old bridge over the Agamok River. Kyle, Matt and I had 20 miles between us and the last aid station, where Levi Lexvold , one of our campaign staff, and Tim Barton, an outfitting guide, would paddle through the storm and set up camp.

Kyle and Matt kept the conversation going with inappropriate jokes, puke and rally stories, while pushing me to down gels and water. The second sunrise of the journey was mostly covered by gray skies, but the light of day was invigorating, and my stomach had turned around, allowing me to feel fueled. The relatively flatter terrain offered some easier running, and the pace picked up.

Our aid station was a buffet on top of an overturned canoe. Tim and Levi had everything we needed ready, and we refueled, put on fresh socks and continued down the trail. The weather held in the 60s and was mostly cloudy, perfect running conditions, and the final miles passed uneventfully.

Erica, the kids and the runners hiked in about a half-mile to welcome me, and we ran as a group to the end. A small celebration was waiting for us with some campaign board members and community supporters gathered. The kids almost knocked me down with giant hugs. I touched the trailhead sign and stopped my watch at 38 hours 15 minutes and 3 seconds for the FKT on the Boundary Waters Traverse.

Next Steps

In the past year, I’ve led more advocacy trips to D.C. than I can remember. There’s one person with a story who sticks out more than any other for what it means to protect this place. A retired U.S. Forest Service Ranger and recounted to members of Congress her days paddling out to check people’s permits and make sure they were abiding by Leave No Trace principles. She shared an analogy for several members of Congress: They, as rangers, had to write tickets to people who were washing their dishes at the lakeside because the water is the main resource that needs protecting. If we’re writing a ticket for food scraps and a little soap for what that can do to the water, how can we possibly allow a massive mining district to leak acid mine drainage into the Wilderness for the next 500 years?

The Boundary Waters is one of the last places on earth where you can drink straight from the lake. Where you can go for days, weeks even, without seeing another human. It’s home to sensitive and protected species and is a migratory flyway. It’s a driver to a nearly billion-dollar outdoor- recreation-based economy in northern Minnesota. of solace, peace, quiet and connection.

Alex Falconer is the government relations director for the Campaign to Save the Boundary Waters. He can usually be found there – either on a canoe trip with his wife and three kids or running the trails that cross this landscape.