New perk! Get after it with local recommendations just for you. Discover nearby events, routes out your door, and hidden gems when you sign up for the Local Running Drop.

Tough new trends in backcountry running

Hal Koerner and Ian Torrence rock through a blackened section of the Colorado Trail. Photo by Richard Durnan.

“I flop to the ground, this time unable to do anything but shiver and sob uncontrollably. Twenty-five miles from the end of the 220-mile-long John Muir Trail, and after 83 hours of nearly non-stop travel, I’m a complete physical and emotional wreck.”

– Peter Bawkin of Boulder, Colorado, recalling his low-point on the John Muir Trail.

John Muir, the trail’s namesake and founder of the Sierra Club, probably did not envision an experience like Bawkin’s or speedy traverses of long mountain trails when he said, “Climb the mountains and get their good tidings.” Still, more and more trail runners are hitting the major trails in search of solace, beauty and, with any luck, new speed records. Call these hearty, adventurous souls a new breed of “through-hikers.” You won’t see them, however, wearing bulky coats, external frame backpacks or leather hiking boots. Instead, these runners train like Olympic hopefuls, don super light gear and plot ways to cover great distances fast.

This summer saw six new speed records on major U.S. trails – plus several failed attempts. Bawkin ran the John Muir Trail in California in 3 days 22 hours 4 minutes; Betsy Kalmeyer of Steamboat Springs, Colorado, became the first person ever to break 10 days on the 487-mile Colorado Trail (9 days 10 hours 52 minutes); just three days later, Hal Koerner of Aurora, Colorado, beat Kalmeyer’s Colorado Trail time – by 33 minutes; Ray Greenlaw of Savannah, Georgia, spent his summer establishing the new record for the 2650-mile Pacific Crest Trail (83 days 5 hours); Skye Thompson of Telluride, Colorado, circled Washington’s Mount Rainier on the 95-mile Wonderland Trail in a record 25 hours 45 minutes; and the very next day, John Stamstad of Seattle, Washington, blitzed the Wonderland Trail almost two hours faster than Thompson (24 hours 1 minute). With this season’s record-breaking frenzy, all signs point at this being the new craze in trail running.

Why are more trail runners going farther than ever – aren’t there enough trail races to satisfy their long-distance appetites? For more and more of them, the answer is “no.” This mega-distance obsession is a little bit about pride and competition, but mostly about personal challenge. As Buzz Burrell, former holder of the Colorado Trail and John Muir Trail records, says, “Expert endurance athletes are now getting on wilderness trails, not for a relaxing respite from their normal training, but instead to commit serious planning, effort and courage to accomplishing a major personal goal.”

Bawkin seconds Burrell’s opinion: “Running is pointless – except maybe to the few who are getting paid. In our society, people do not challenge themselves very often or very deeply. These types of events do just that. Overcoming obstacles brings rewards that are not always tangible, but definitely worth the struggle.”

Kalmeyer, an accomplished endurance athlete and the only woman to ever break 30 hours at the insanely difficult Hardrock 100 Mile Endurance Run, had dreamt of running the Colorado Trail for several years. Finally, she felt ready and had enough free time to attempt it. “Plus,” she bashfully admits, “maybe turning 40 had something to do with it.” This was the ultimate physical and mental challenge for her – a life-defining run.

Says Greenlaw of his record-breaking journey on the Pacific Crest Trail (PCT), “To break this record took essentially a lifetime of mental and physical preparation. I put myself through all sorts of purgatory to set the record and knowing I was strong enough makes typical everyday struggles a breeze.”

But whether the driving force is personal discovery or trail-running glory does not change the challenge and grueling difficulty of undertaking a trail-record attempt. Months and, sometimes, years go toward planning one. Map out the logistics. Become a student of the trail. Coordinate the crew and find a vehicle that can handle the miles. Plan the drop-offs for supplies. Save your money. Arrange the time off work. Train … a lot.

Photo courtesy of Ray Greenlaw Collection.

The plan of attack for any trail records depends on a number of factors. On the Wonderland Trail, Stamstad went with a minimalist approach; he took only the necessities with him and relied on strategically placed supply bags along the trail. Of course, he could do this because of the accessibility of the trail. It also helped that his record-setting run took only 24 hours.

Kalmeyer, on the other hand, needed a crew to follow her along her Colorado Trail journey. Her boyfriend, Dick Curtis, drove over 1000 miles on suspension-wrecking jeep roads to meet her at different points. She’d emerge from the forest, inhale chicken-noodle soup, Pepsi, potato chips, hot dogs or a burrito, trade out gear if necessary, and then vanish into the woods for another 15 or 20 miles.

In more extreme adventures covering thousands of miles – such as the PCT or the Appalachian Trail (AT) – years of logistical planning are required to coordinate supply drops at general stores and post offices along the routes. Sometimes, runners will even hitchhike from the trailhead to the nearest town for hot food or a lumpy mattress at a motel. The possibilities are endless and that’s all part of the fun – tackling such a colossal challenge inevitably requires some creativity and problem-solving along the way.

The preparation is enough to qualify as a full-time job. Dave Horton of Lynchburg, Virginia, knows the game well. The former record holder for both Vermont’s Long Trail and the AT, Horton advises would-be trail-record seekers to take a look inside their heads. “[Challenging a trail record] requires that you accept for a certain amount of time your life will be only running, eating and sleeping. The question becomes, are you smart enough to listen to your body?” says Horton. “You’re going to destroy yourself for a while, and there will be low points. But you have to want it. Are you willing to pay the price?” On his AT attempt, Horton exemplified such toughness; his ankles swelled wider than his shoes and he peed blood.

Running consecutive 40-mile days for several days simply breaks down the body. It’s elementary math: 40 miles of running equates to almost 5000 calories. That’s roughly two Thanksgiving dinners per day, just to maintain. On top of caloric needs, injuries are common and, in almost every case, expected. Add it all up, and trail records are the ultimate frontier of pounding the body through barriers of fatigue, exhaustion and injury.

This summer, veteran trail runners Ian Torrence and Koerner began their quest for the Colorado Trail record together. It was to be a grand accomplishment for two pals sharing a passion for big challenges. From the start, however, an injury to Torrence’s IT Band threatened to cut the journey short. He was willing to nurse his knee pain through 320 miles, but even trail-running super heroes have their limits and he had to stop with 170 miles to got. “I was bummed I couldn’t finish and I had to swallow a little pride and ego,” says Torrence. “The pain was too much.”

And if the physical and mental demands of running long trails over several days don’t ruin the hopes of the greatest trail runners, there is always the most powerful variable of all: luck. Luck can be a gust of wind blowing a tree branch out of the way just long enough to spot a trail sign. Or it can be a freakish storm bringing sideways snow to a ridge that moments earlier bathed in sunlight.

Koerner felt the bite of bad luck in his Colorado Trail record attempt. Later on the same day he said good-bye to Torrence, he ran through a thinly marked section of trail high on a ridge. Fog materialized and visibility disintegrated to poor. Then his headlamp malfunctioned, leaving him with only a dim LED for route finding. He missed a crucial turn-off, descending thousands of vertical feet down the wrong side of a mountain. As his support crew worried and even contacted a local mountain-rescue unit, Koerner wandered through the Rocky Mountains alone. Finally, at 6 a.m. the next morning, he found his way to the meeting point. Luck went against him and, ultimately, almost cost him the record. Recalls Koerner, “As I wandered around, it was my greatest moment of doubt. I felt like I went 100 miles that night.”

Out on the PCT, Greenlaw danced with Lady Luck many times. “To break the record, I had to be lucky with the weather and fires,” he says. “Plus, there are so many other things that could go wrong. If a bear takes your food, you’re screwed. If you get giardia, that’s it.” Fortunately for Greenlaw, the weather held steady and the forest fires didn’t flare up during his journey. In the time since his record, however, sections of the PCT in Oregon and Washington have closed due to fires. Lady Luck … she ‘s fickle and plays favorites.

If everything works in the runners’ favor, and their legs carry them to the end of the trail, they must receive massive recognition, ticker tape parades and book contracts. Right? Nope. There may be a few family members, crew helpers and a bottle of champagne, but that is it. Some record setters cry, others hug trailhead sign and some even laugh uncontrollably. Oddly enough, there is a common element to many broken records: beer. For Stamstad, his Wonderland Trail record was savored alone, in a trailhead parking lot, while drinking a Rainier Beer. After a hot shower, koerner and his crew gorged on pizza and – what else – Colorado Trail Ale. And Ed Kostak, upon setting a new standard for running Vermont’s Long Trail, sat on the Vermont/Massachusetts border and swigged a bottle of Long Trail Ale.

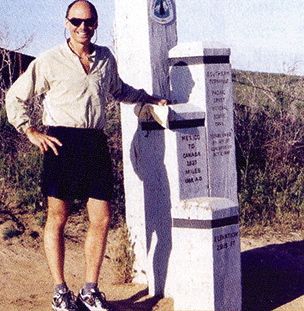

California Dreamin’: Peter Bawkin jams on his way to the John Muir Trail record.

If he could hear the stories of suffering, frustration and record-seeking, would John Muir roll over in his grave or applaud from the heavens above? What would other famed pioneers and explorers – Lewis and Clark, Sir Edmund Hillary or Ernest Shackleton – say about it all? Critics feel running these famed routes for speed goes against the very idea upon which many were established – to provide an escape from society’s pressures, commercialism and fast pace. The purpose of these trails, some may say, is to provide a safe haven from all of that. In fact, some trail organizations will not even recognize such speed records. In 2002, the Colorado Trail Foundation Board of Directors adopted the following policy statement regarding competitive events and activities:

“Competitive events and activities on The Colorado Trail are not compatible with the mission of The Colorado Trail Foundation or the Foundation’s vision of The Colorado Trail. We do not endorse such events or activities or keep any records with regard to them.”

Brian King, director of public affairs at the Appalachian Trail Conference, says, “We don’t recognize any speed records for hiking, running or walking the AT, primarily because we have neither the resources nor the desire to validate claims in a credible manner. We can’t stretch ourselves into being a ‘mini-Guinness’ or a governing body for the sport.”

On the other side of the issue, advocates of trail records see their mission as an expression of Muir’s ideals or, more generally, self discovery through nature. Brian Robinson, the only person to every complete the AT, PCT and Continental Divide Trail in one year (known as the “Triple Crown”), says, “I am glad that more attempts are being made on major trail records. The challenge adds spice to an already wonderful experience.” And, with an attitude that would bring a smile to Muir’s bearded face, he says, “I hope that no one going for one of these records gets so caught up in the attempt that they miss the joy to be found in the wilderness. The power of wild places to transform one’s spirit is more valuable than all the records in the book.”

Unwritten Rules of Engagement

Setting a trail record seems simple enough: cover every inch of the trail by foot, from beginning to end, faster than anybody else. But for every major trail, there seems to be a disputed record – and even a hoax or two. If you tackle a trail record, avoid the scrutiny. Tackle these rules:

1. Advertise your intentions. You don’t need to shout it from the mountaintops, but you should not “sneak under the radar” either. Send a press release. Create a simple website. Email your friends, fellow runners and the local running club. Just gt the word out. Many runners also contact the current record holder to honor their accomplishment and sometimes even ask for pointers.

2. Share your record. Do not privately go about your adventure. Invite other runners to join you – they can crew, pace or just cheer you on. The more people witnessing an event, the more credible it is.

3. Write everything down. The more documented your trip is, the more validity it will hold. Sign all trail registries. Keep a journal. If possible, post entries online. Years later, when many details of your trip are forgotten, you will appreciate this reminder, too. Photographs beside trail signs provide additional proof.

(Adapted from “Long Days & Lonely Nights,” by Buzz Burrell, Trail Runner, April/May 2001.)

“Um, Boss, can I have the next three months off?”

If you’re one of the fringe-of-the-fringe trail runners who hopes to tackle an uber-distance trail record, you have plenty of options. Here are the “FKTs” (fastest known times) for some of the classics. [Records as of January, 2004.]

Pacific Crest Trail

>Length: 2650 miles. Linking Mexico to Canada through California, Oregon and Washington.

>Beware: Diversity of elevations and terrains, poor trail markings, forest fires and river crossings.

>Record: Ray Greenlaw, 2003 (83 days 5 hours)

Appalachian Trail

>Length: 2160 miles. Georgia to Maine.

>Beware: Roots, ticks, humidity.

>Record: Peter Palmer, 1999 (48 days 20 hours 11 minutes)

Tuscarora Trail

>Length: 252 miles. Spur of the Appalachian Trail running from Pennsylvania to Virginia.

>Beware: See AT above, plus briars and sporadic trail markings.

>Record: Joe Clapper, 200 (3 days 22 hours 27 minutes)

Colorado Trail

>Length: 487 miles. Through the Colorado Rockies, from Denver to Durango.

>Beware: High altitude, extreme weather, 76,477 feet in elevation change.

>Record: Hal Koerner, 2003 (9 days 10 hours 19 minutes)

Continental Divide Trail

>Length: 3100 miles. Canada to Mexico, along the crest of the Rocky Mountains. Five states, 25 national forests, 20 wilderness areas and three national parks.

>Beware: Still under construction (70 percent usable) , rugged and remote, dry and hot on the southern end (NM).

>Record: Brian Robinson, 2001 (88 days – in two stages due to inclement weather and snow)

John Muir Trail

>Length: 220 miles. Mount Whitney, California, to Happy Isles, California.

>Beware: Mountain passes between 12,000 and 13,000 feet, Mount Whitney summit (14,494 feet) and cold nights.

>Record: Peter Bawkin, 2003 (3 days 22 hours 4 minutes)

The Long Trail

>Length: 273 miles. Oldest hiking trail in the U.S. Runs the entire length of Vermont, along the spine of the Green Mountains.

>Beware: Technical footing in the north, heat, humidity and mud. 135,000 feet of elevation change.

>Record: Ed Kostak 2000 (4 days 15 hours 19 minutes)

Wonderland Trail

>Length: 95 miles. Circles Mount Rainier, Washington.

>Beware: Weather, snow, 24,000 feet in elevation change.

>Record: John Stamstad, 2003 (24 hours 1 minute)

This article originally appeared in our January 2004 issue.