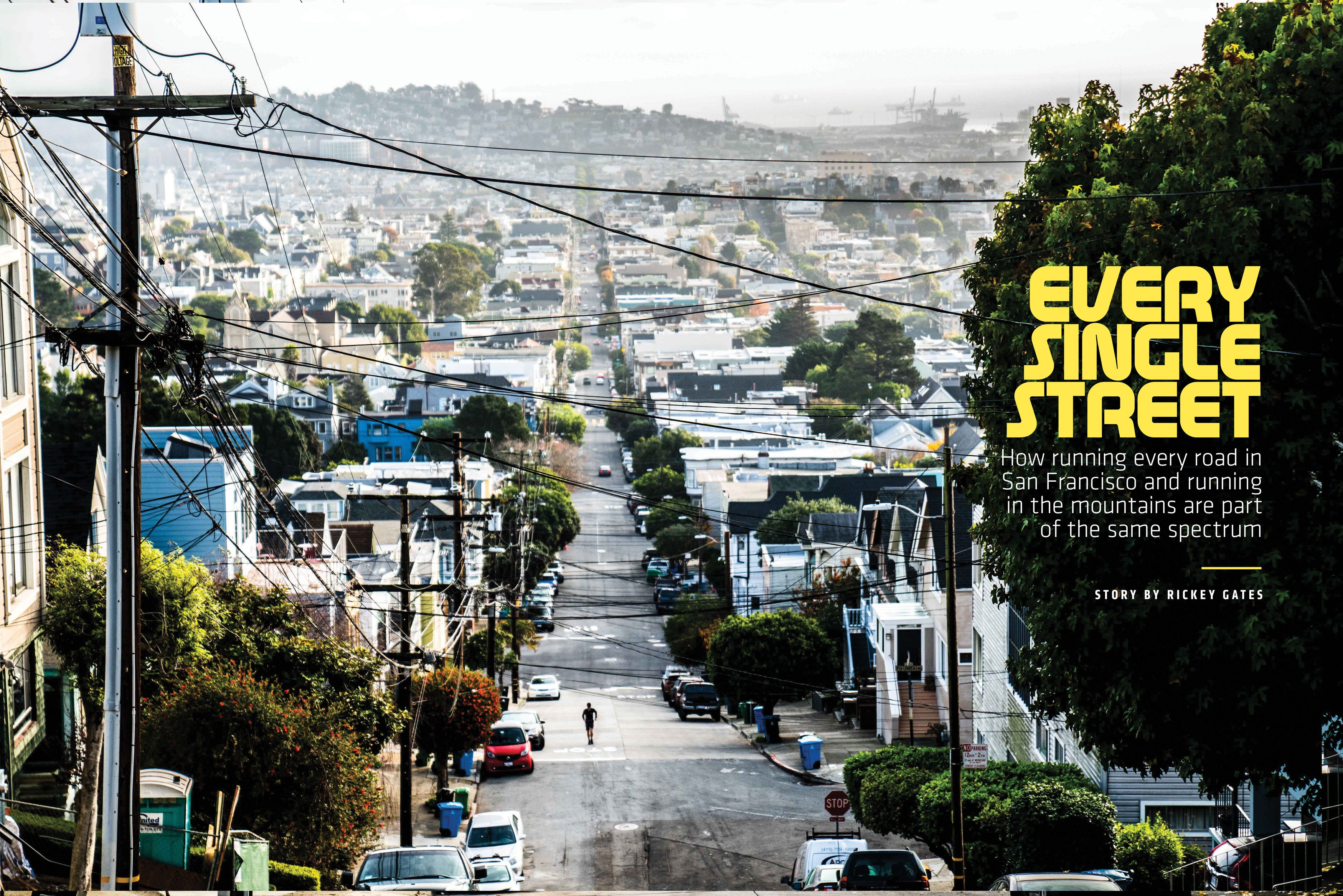

Every Single Street

Ocean Beach—Day One,

November 1, 2018

“Hey man! What the fuck?”

I glanced over at the surfer half changed out of his wetsuit to see who he was yelling at, only to find that it was me.

“What the fuck are you doing?” he yelled, pointing at my small camera that was sitting on the concrete berm alongside me. Though the camera was off, it just so happened to be pointed at him.

I had sat down to watch the waves crashing and seagulls floating and to take my mind off the immensity of the project that I had just begun only hours before. Nothing was going well. It was unseasonably hot for San Francisco, my Halloween hangover continued to linger, my phone was still missing and now a disgruntled surfer appeared ready to brawl under the suspicion that I was taking photographs of him changing.

I told him that the camera wasn’t on, that it was coincidental that it was pointed in his direction. I offered to show him my most recent photos to prove that I wasn’t taking any photos of him.

“Just don’t take my fucking picture, bro.”

I had recently seen a short film about a surfer. He looked out at the chaos in the water and with a calming South African accent proclaimed, “The Ocean … when you’re out there, you become a part of it, and it becomes a part of you.”

Bro? I thought. I should have continued on, but I couldn’t shake the surfer’s rage that was quickly becoming infectious. If he has become part of the ocean, I thought, and the ocean has become part of him, what part of the ocean had he just visited?

“How was the surf?” I asked.

“This conversation is over,” he said. “Have a nice day.”

“That good, eh?”

“I said, ‘This conversation is over,’” he repeated. “Have a nice day,” which, by the tone of his voice and everything else, suggested he didn’t really mean it.

A year ago, I had finished running across the country right there at Ocean Beach [see “To Have Run Cross Country,” Issue 127, April 2018]. Staying on in the Bay Area for the weeks and months that followed my run and observing the intricacies that contribute to create the conglomeration of people and infrastructure made me quick to acknowledge that the route that I had created and traveled was but a thin line across the country. Now living in a city, I reflected on how relatively quickly a city would pass beneath my feet—that, in contrast to the hundreds of miles of vastness, passing through the city felt like just a few short strides.

The 3,700-mile run taught me a great deal about the land and people that make up this incredible patchwork of culture and terrain. It gave me a new appreciation for a full spectrum of environments, shaking the binary belief system of wilderness versus urban that I had subscribed to in the past: In this place, Mother Earth is in control; in that place, Human Kind is in control.

My trek taught me that to think of environment in that way was a luxury of cars and planes getting us to start lines and trailheads—that, in reality, all environments, from the depths of the Grand Canyon to 5th Avenue in Manhattan are part of the same spectrum.

To truly appreciate any of these environments, I concluded, warranted giving equal effort to the extremes. To spend an intense period of time in the city was the only logical progression and, having been a resident of the Bay Area off and on for over five years, San Francisco seemed to make the most sense. In a masochistic sort of way.

I left the surfer and his rage and continued south along the Great Highway, skirting the Pacific Ocean, toward the southern border of San Francisco. I was 13 miles into what I had estimated would exceed 1,300 miles to run every single street in a city that measures barely seven-by-seven-miles square.

Visitation Valley—Day 10,

November 10, 2018

The smoke from what is being called the Camp Fire northeast of Sacramento had destroyed thousands of acres of forest and personal property, and killed several dozens of people. Now the smoke was being carried directly over San Francisco. I bought a cheap face mask that helped keep much of the smoke out of my lungs allowing me to maintain the 30-mile-per-day mileage I needed in order to finish this project before Christmas.

I had been chipping away at the southern part of the city where, unlike those defined by the bay or the ocean, the city’s limits are seemingly arbitrary. With map in hand I clicked off the various neighborhoods, most of which I’d never visited before and some that I’d never heard of. Excelsior, Stone’s Town, Lake Merced, Lake View, Outer Mission, Little Hollywood and Ocean View. As each neighborhood passed beneath my feet, I struggled to improve my method for covering every block of every street in every neighborhood without backtracking or leaving any to be done on another run.

A winter prior, I mentioned this idea to Michael Otte, a friend from high school, whose life path led him to math, engineering and a professorship at an East Coast university. Our chance encounter on a snowy Colorado mountain top couldn’t have contrasted more with the project we were discussing. His long, almost-white hair and wild Viking beard accentuated his excitement as he explained to me that, if I were to attempt running all the streets with any sort of efficiency, I was, in fact, solving a famous math problem called the Chinese Postman Problem.

On that brisk morning I received a brief introduction to Otte’s line of work, a layman’s lesson on graph theory, and how this problem was in fact a variant of the more famous Traveling Salesman Problem. Where the Traveling Salesman Problem takes a bunch of points and connects them with the least amount of distance, the Chinese Postman makes sure that every line between those points is also covered at least once, you know, to deliver the mail.

I should have known from his enthusiasm that this challenge would not be a simple problem and that doing it wrong or poorly would result in extra miles … which is only a word until you have double backed on a block several times and know that you could have done much better if you’d have just stopped and thought about the problem to begin with.

On Arleta Avenue, I chased down an older gentleman who had accidentally dropped a shirt on his way to the cleaner. His tall frame moved slowly. Unlike most of us out on the street, he was not wearing a mask.

After I handed him his shirt, our conversation quickly went to the smoke. The smoke was ubiquitous, not just in the air, but in people’s minds.

“This smoke is bad,” he said in a voice that wasn’t quite Southern.

“Sure is.”

“Real bad. Cause people ain’t prayin.’”

“You pray?” I asked.

“Every day.”

“You pray for rain?”

“I pray for everything!”

He went into the cleaner while I carried on down the street.

Potrero Hill—Day 20,

November 20, 2018

Having run all of the north-south streets of Potrero Hill the previous day, the following day I planned to click off all of the east-west streets in the same area. Located just south of downtown and adjacent to some of the oldest docks on the West Coast, Potrero Hill sits apart from the other hills in the city. Though only 300 feet tall, the hill boasts some of the steepest streets and deepest history.

Around its base lie emerging tech companies and hospitals while quaint houses and old-time bars crawl toward the summit. I anticipated adding another 6,000 feet of climbing to the 50,000 feet of vertical that I’d accumulated thus far. If done efficiently, it could be run in 27 miles or so, but it would likely take me closer to 30, adding to the 600 miles I’d already run.

The rain had been falling off and on throughout the day. My paper map had all but disintegrated. The smoke was gone. Truly, it felt like the city was finally being washed.

The gingko trees had all turned a bright yellow, many of those leaves already making their migration toward the ground, the gutter or possibly a trash bag. The magnolia trees had already lost their heavy brown leaves, revealing the new buds for the coming year.

I continued to think a lot about the mountains and wilderness during this endeavor—how we go to the mountains because we need a break from the city—the noise, the crime, the hustle, the poverty, the graffiti, the smell.

Growing up in the mountains, I saw these people that came to the mountains and had absolutely no clue. They tried to make up for it in clothes and shoes and a handsome guide. But it’s not something you can hide. Twenty-five years later, I’m that guy, but the wilderness is the city, and my mountain is a 300-foot hill that I’ll go up and over at least 13 times today.

I crossed the streets, one after another: Vermont, Kansas, Rhode Island, Wisconsin, Arkansas, Connecticut, Missouri, Texas, Mississippi, Pennsylvania, Indiana, Minnesota, Tennessee, Illinois, Michigan. I reached the Bay and turned around.

Golden Gate Park— Day 34,

December 5, 2018

“Turn right on to Spreckles Lake dee arr,” the woman’s voice in my pocket said. A glitch in the program had her saying the abbreviation for “Drive” as the two separate letters. She was actually an it—a computer program that Professor Otte enlisted to interpret his algorithm on which we have finally worked out most of the kinks.

“Turn around,” she said to me as I approached the dead end.

Over a month into my run, mapping my route day to day, hour to hour and block to block reigned as the most challenging part of the run. Though Otte’s algorithm was finally detecting the shortest possible path needed to cover an entire predetermined area, we were challenged by how to convert the results into a format that would allow me to move quickly. Golden Gate Park provided simple enough parameters for the signal in my phone to determine my location and anticipate the intersections spaced far enough apart to not be confused with another intersection.

I had saved the park for a day when I thought I might need something that felt like wilderness, or, if not wilderness, at least nature. I recalled a quote from Benton MacKaye, the creator of the Appalachian Trail and an outspoken proponent of the need for wild places: “However useful may be the National Parks and Forests of the West for those affording the Pullman fare to reach them, what is needed by the bulk of the American population is something nearer home.”

Over the previous days I had finished off both the Sunset and the Richmond districts—two of the youngest neighborhoods in the city, built upon rubble brought over from the dense downtown, replacing the sand dunes that had otherwise made the districts unsuitable for much more than sand castles. The mostly Chinese demographic of the two neighborhoods ensured a steady supply of dim sum and dumplings for my efforts while the simple layout of the neighborhoods allowed for easy navigation, even allowing me to leave my map in the car.

South on 34th Avenue, the streets descend alphabetically through the historic surnames that helped shape the city in its early years: Irving, Judah, Kirkham, Lawton, Moraga, Noriega, Ortega, Pacheco, Quintara, Rivera, Santiago, Taraval, Ulloa, Vicente, Wawona.

And then north on 35th Avenue.

Wawona, Vicente, Ulloa, Taraval, Santiago, Rivera, Quintara, Pacheco, Ortega, Noriega, Moraga, Lawton, Kirkham, Judah, Irving.

In the Richmond, I met Ben working on an old Datsun. The engine was out of the car, sitting in the garage nearby, the wires and tubes meticulously taped up. Ben was sanding the frame by hand. Athletically squatted on his haunches, his stance suggested that it was also his workout.

“It’s a labor of love,” he said. “Most people don’t get it.”

He’s accustomed to explaining or justifying his hard work on something that is beyond most people’s comprehension.

“I get it,” I said. He smiled and knew that I did.

Overhead, a distinct sound like a dog’s squeaky toy flew over. We both looked up to spot the Parrots of Telegraph Hill, which playfully travel about the city spreading their call that is familiar though not exactly song-like.

The feral parrots brought up from the Amazon as pets and likely freed as a result of their abrasive song have made the city their home over the past hundred years. Whenever they fly past, I look around me to see who else is paying attention to the birds. Right then, though, it was just Ben and me.

Golden Gate Park separates the two neighborhoods with trees, lakes, museums, coyotes, dirt and bison. It provides a quiet place, “nearer to home.” On that cold, rainy weekday, it was providing me with a 23-mile route that was simple enough for a computer program in my pocket to tell me where to go.

“Turn left on 36th Avenue,” it said.

SoMa—Day 39,

December 9, 2018

We try to make sense of places at first by seeing them and then by labeling them. SoMa (an abbreviation of South of Market) has been a place of industry, commerce, trading and human-rights protests, and continues its paradoxical trend as a site of both great prosperity and immense poverty, living side by side. AirB&B, Salesforce, Adobe, LinkedIn—names that I’d only ever seen in digital form take shape in converted warehouses and brand-new SoMa buildings that only tech can seem to afford.

In running every street in this city, I forced myself to observe the good and bad on equal levels. In pursuing this project, I positioned myself within the depths of this human wilderness where hope is everything and hope is nothing.

Just down the block from the headquarters of Twitter, a man is lying down on a damp piece of cardboard, his spent needle, clear and orange, just beside him. Another few blocks away, the second tallest building west of the Mississippi protrudes into the sky.

On that day in early December, I walked rather than ran. It felt entirely too strange to be a tourist down some of these dead-end alleyways where people are setting up camp with the last of their possessions, living from needle to needle. The conscious ones I looked in the eye and nodded.

The ideas of wilderness and mountain tops seemed so foreign to me at that moment. The feelings that they evoke in me however were right there—fear, confusion and a great desire to understand them better.

Downtown San Francisco—Day 45,

December 15, 2018

The city confronts you with all the things you don’t know and don’t understand. It makes you make sense of them. In any way you can.

To run across a place is to observe and participate in a vast, intricate and complex web of infrastructure. It is to experience the history of that place in a very real and personal way. It is to have a better understanding of what that place is. Where that place is. Who that place is. Why that place is. Is that why it spits so many people out? And is it actually all that different from the brutality of the mountains?

My accumulation of fitness allowed me to cover the bulk of the city’s downtown attractions in a single day: Fisherman’s Wharf, Nob Hill, Telegraph Hill, Little Italy, China Town, the Civic Center and Russian Hill. Again, I felt like I was doing an injustice by covering such a dense area in such a short period of time, but I felt like both my mind and body were ready for it.

Trance-like, I meandered through the canyons of tall buildings and tunnels below the hills with the same joy and clarity that had carried me across the Rockies or Great American Desert a year prior. I was feeling, not thinking, moving, not running, listening, not hearing.

Twin Peaks—Day 46,

December 16, 2018

The roof of clouds descended, and the rain started falling as I approached the summit of Twin Peaks, where the final miles of my run were taking me to what I had hoped would be a view of all the ground that I had covered over the previous six weeks.

If it was a clear day, you could see right down Market street—the street cars moving along, buses, taxis, bikes and scooters jockeying for position.

If it was a clear day, you’d be able to see the cars coming and going across the Golden Gate Bridge and the Bay Bridge. If it was a really clear day, you could see the same on the San Mateo Bridge and San Rafael Bridge.

If it was a clear day, you’d be able to see the gantry crane at Hunter’s Point and the dog walkers of Bernal Heights.

If it was a clear day, you wouldn’t be paying quite as much attention to the feel of the city below.

The life pulse of it wouldn’t feel quite as palpable. But you can hear it, smell it and feel it, and you know it’s there because you’ve become a part of it, and it’s become a part of you.

With these final 22 miles and 3,500 vertical feet of climbing, the journey to the heart of the city has matched the distance it took me to run from Denver to San Francisco and equaled the climbing equivalent of five times up Mount Everest from sea level. With this level of exertion comes an emptiness that lends itself to profound understanding—an understanding that leaves words at the door—an understanding of the most peculiar wilderness of them all, the wilderness deep inside the human hive.

Following the completion of this endeavor, Gates took to the streets again in Mexico City. The “tourist edition” of Mexico City took him through a dozen neighborhoods and over 250 unique miles.