Vision Quest

Reconnecting heart & home in Wyoming’s stunning Jackson Hole, Wyoming

This article originally appeared in our November 2006 issue.

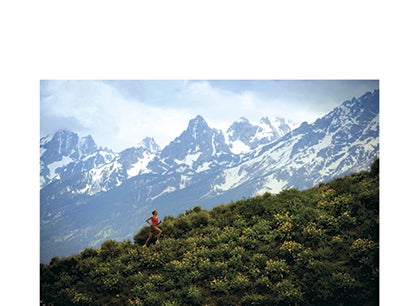

The author reconnecting with her previous home in the Jackon Hole valley, here in Grand Teton National Park.

Photo by David Clifford

When I see their shimmering, silver-tipped leaves dancing jubilantly in the wake of an afternoon thunderstorm, I sense these aspen trees remember me and are marking my return. Their brilliant white bark illuminates Highway 89 along the Snake River, guiding me back to the valley where I grew up. My core cracked open, I surrender to the aspens’ embrace, slightly mystified that I haven’t missed them until now.

Photo by David Clifford

The Jackson Hole valley lies nestled in the northwest corner of Wyoming just south of Yellowstone National Park. To the west, it is sheltered by the craggy Tetons and borders the Gros Ventre Wilderness to the east. At over 6000 feet above sea level, the Snake River and her tributaries traverse the sage-covered valley floor. I am not alone in thinking that Jackson Hole is the loveliest place on Earth—nearly four million tourists from all over the globe visit the valley each year. Strangely, I am now one of them, making this pilgrimage during the summer solstice to run the trails I grew up guiding with my family’s backpacking outfitting business.

Photographer David Clifford and I meet up in the wild-west-themed town of Jackson (Jackson Hole is the name of the valley; Jackson is the main town) and strike out for the trails of Grand Teton National Park. Stacked, puffy cumulus clouds drift overhead as we make the spectacular 15-minute drive from town. David and I board the ferry crossing Jenny Lake (named for the Shoshone wife of fur trapper “Beaver” Dick Leigh) intent on revisiting the pine-forested paths well-worn by my family.

The ferry drops us near Inspiration Point and Hidden Falls. David shoots me a look of horror as we’re herded in with the tourist throngs for an orientation speech from a Park employee.

“This place is like Aspen on steroids,” David says, disillusioned.

“Follow me.” I tug on him and we slip off, making our way along the less-worn Lake Loop Trail. After about a mile and a half, we see only pale yellow columbine, Douglas fir and flaming red Indian paintbrush, the state flower of Wyoming (I remember this from Girl Scout camp). A bit further down the trail we come across a gothic teenage girl from Akron.

“Shhh …,” she says, wide-eyed. “Look.”

She’s fixated on a yellow-bellied marmot. David, a seasoned Colorado Rockies man, rolls his eyes as if she were mesmerized by a cow or pigeon in our path.

I’m suddenly reminded of what it was like when my family first moved to the valley from California in 1978, and what a magical wonderland it was to us. I sense the awe pulsing through the girl, who is normally disconnected from nature, plugged into her iPod or myspace website. For her, a whole world has just become available—call it a marmot moment. Here is the real beauty and power of this place: It takes hold of you and brings you into its fold until you are no longer in the landscape, but, rather, the landscape is within you.

Gemma May and Bridget Crocker pounding out an afternoon run in the Gros Ventre.

Photo by David Clifford

The astonishing, 13,000-feet Tetons themselves were formed by slippages and earthquakes caused by the Teton Fault. The mountains had been hidden underground in the high plains until they cracked through the earth’s crust, rumbling their way into this dimension. Thousands of years of glacial ice then sculpted the range’s finer details. Beauty like this doesn’t come gently or easily; it’s hard-earned, created by epochs of dramatic tectonic force and glacial pressure.

David and I hook up with local trail runner, Zach Barnett, for an afternoon run along the Valley View Trail stretching along the base of the Tetons. Barnett, who is co-director of Grand Teton Races along with ultrarunners Lisa Smith-Batchen (see Making Tracks, page 14) and Jay Batchen, frequents the Valley View Trail as a training ground for the annual three-race event.

“Last year [during the races] we had the most incredibly rough conditions: sleet, hail, rain, bears in the middle of the night,” says Barnett. “It was really exciting; everything that could go wrong weather-wise did go wrong.” The lanky, uber-fit Barnett laughs almost gleefully as he bounds up the trail, hardly sweating. Strawberry-haired and charismatic, Barnett appears like the Robert Redford of the Rockies, vibrating with an intensity matching the cascading creek alongside the trail.

We’re headed toward Death Canyon, a 10-mile round trip jaunt through old-growth pine and aspen groves. From the occasional clearings, we catch glimpses of the gently sloping, emerald-forested Gros Ventre range across the valley, as well as the lumbering Snake River.

I’m starving, having run out of reserves trying to keep up with the relentless Barnett. Somehow, David is managing to keep pace while lugging heavy camera equipment. I’ve forgotten how hardcore the outdoor culture is here; I’ve been an ocean dweller long enough that my rhythm now moves more gently, like the tides. Every so often I hit pockets of fallen, sun-seared pine needles, their sweetness satiating me like thick ambrosia, warming the pit of my stomach and soothing the jagged, hunger edge.

I come loping around a bend, fixated on a yellow swallowtail butterfly gently floating upward and nearly flatten Zach, who’s halted mid-stride, hand held up in warning. I follow his gaze to a young cow moose (my fifth moose sighting today) chewing on willow as God rays beam down, highlighting her horse-like snout and the yellow arrowleaf balsamroot blooming around her. The Grand Teton, also known as Elder Brother to the Shoshone tribe, stands behind her protectively while thick-trunked aspens sashay in the breeze.

Photo by David Clifford

Later that night, I receive a call from my younger brother, Josh Mahan, from his home in Missoula. He and his marathoner girlfriend, Jennifer Sauer, are anxious to do some running in the Gros Ventre, where Josh and I have worked countless backpacking trips with our folks over the years.

“I’ve been looking at maps all week,” Josh says, “and I think we should do Cache Creek to Granite Hot Springs.”

This is an ambitious intention, considering the Cache Creek trailhead is in town and Granite Hot Springs is an hour and a half drive up the Hoback to the south.

“Is there even a trail that links them?” I ask dubiously.

“Howie used to winter-ski it in an afternoon. I remember picking him up at Granite.” Howie Wolke is our stepfather and a man widely known for undertaking epic wilderness journeys—usually solo—over vast chunks of seldom-trod land. Drop Howie naked in the middle of grizzly country, and he would emerge months later well-fed and thriving.

“Yeah, but do you see a trail on the map?” I ask my brother, who, like me, has learned most of his wilderness skills (including map reading) from Howie.

“We may be on game trails but, yeah, there’s a route. It’s about 13 miles over the ridge. If we get an early start we can make it in time to soak in the hot springs.”

I have no reason not to believe him. We make plans to meet up the next morning at Granite Creek to set the shuttle.

David and I whiz along the southern end of the valley through grey and yellow shards of early morning light. We pass by the home where Josh and I grew up: our sledding hill by the Snake, the cottonwood grove where we built forts and gathered morel mushrooms. David is a good sport, humoring my memory-lane monologue.

“My mom used to load us up and take us to Granite Hot Springs. My brother loved to play this game, Blind Man, in the pool there,” I say. “He’d walk around aimlessly with his eyes closed, trusting that someone would point him in the right direction—someone usually meaning me. He was so cute with his long eyelashes wet and poking out like a baby elk, I couldn’t let him just smash into the pool wall.”

Josh and Jenn are ready to go when we arrive at their Granite Creek campsite. We leave a car and head back to town, stopping in at Bubba’s Barbeque to carbo-load before entering the Gros Ventre, named for the Gros Ventre Indians who now live in north-central Montana. The French trappers mistakenly called the Gros Ventre Indians the “Big Bellies” because of the stomach-rubbing hand signal used by other tribes to represent the mountains. The Gros Ventre call themselves the White Clay People, believing that they were originally created from the earth found below water.

Crocker on the Cache Creek-Granite Hot Springs adventure, Gros Ventre Wilderness

Photo by David Clifford

Our small group arrives at Cache Creek, a local trailhead well-loved by mountain bikers and runners for its easy access. Five minutes from the town square where RVs vie for parking spots and we are in an expansive 455,000-acre wilderness paradise. With luscious sub-alpine meadows, spongy, moss-lined springs and stunning limestone peaks, this pristine area supports grizzlies, black bears, moose, elk and mountain lions.

“I brought bear spray,” my brother volunteers as we load up our gear. Jenn, her long blond hair glistening in the midday sun, sports a delicate fanny pack while checking her GPS somewhat anxiously. David fills his pack with lenses, filters and a water bottle. Josh and I both don unwieldy, overstuffed day packs.

“What do you have in that thing?” David snorts as he hands my pack to me.

“First aid. Food. Supplies for evacuation.”

“I doubt we’ll be doing any evacuating,” says David, laughing.

“Girl Scout motto: ‘Be Prepared’,” I counter and start up the trail, lagging behind the wonder couple who, like antelope, have disappeared from view with a few hops.

We ascend snow-covered ridgeline after ridgeline, stopping every so often. Josh checks the map while Jenn reports the mileage from her GPS.

“Nine miles,” she says as we chew on jerky. We’re laughing. This is delightful: views of the monolithic, ice-covered Tetons tower behind us, gurgling creeks filled with snowmelt. Josh and Jenn even glimpse a black bear in a meadow below.

The path all but disappears and we’re threading our way along game trails, hugging the limestone cliffs. The light starts to scatter as the sun dips down.

“Fifteen miles.” We’re muddy and our lips are sunburned. Sweat has drenched and dried on us more times than we can count. Jenn nervously declares that she does not intend to run in the dark.

My little brother hands me the topo map, as if it were a jar with a lid in need of loosening. I spread the map out in the twilight, matching contours to features. There’s a perceptible shift inside of me, a rumbling knowledge of what’s about to unfold and the level of intensity required to survive it.

“This way!” I take to a faint trail spurring high along the base of the limestone cirque. We have been pretending that it’s not dark for several miles now. Josh and I break out headlamps from our giant daypacks.

“Are we going to spend the night out here?” asks Jenn, as Josh gives her his light.

“I’ve got a space blanket,” Josh reassures her.

“Let’s keep going.” I’m all business.

Miles pass, marked by the movement of infinite stars, more coming into focus the further into night we venture. David follows closely behind me, gleaning what he can from my dimming light. The trail becomes blocked by downed trees, which we strain to bypass, losing our trail in the process. I pause, opening wide that space inside my core that is this land, this place formed by hardship and drama.

Over here, the aspen trees whisper through the darkness, leading me instinctively back to our path.

“How are you seeing the trail?” David asks me after we lose and recover it several times. He’s perplexed since my light has all but died.

“I’m not so much seeing it as feeling it,” I explain.

We push on past midnight, until we finally arrive to the steep switchback descent. Lights across Granite Creek come into view.

“Look, there are the lights of my old Girl Scout camp,” I point out.

Jenn informs us that, according to her GPS, our 13-mile adventure is actually more like 23 and a half. “I’m ready to be out of here,” she says.

I touch the luminescent bark of an aspen as gently as a loved one and know that even if I am out of this place, it will never be out of me.