Running the Qhapac Nan

The chaski relay system in the ancient Incan Empire

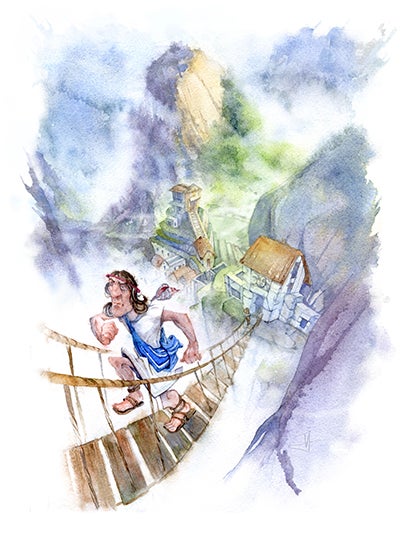

Illustration by Daniel Yagmin

The blast from a conch shell cuts through the cold Andean night. Lying beside the embers of a dying fire, you hear the patter of footsteps running on cobblestones. You jump to your feet and grab your sling and conch shell before ducking out of your stone hovel and onto the “Qhapac Nan,” the Incan Royal Highway, the Incan Empire’s sprawling road system.

You know this section like the back of your hand. Two miles in either direction is your exclusive domain. At 12,000 feet, oxygen is scarce, but you can still run a six-minute mile. A runner dressed in a white robe approaches and hands you a knotted cord that bears a message for the King. He whispers the message’s final destination in your ear and you begin to run toward the next outpost.

You are a chaski runner, a relay messenger in the ancient Incan empire.

Between the 13th and the 16th centuries, thousands of chaski runners were positioned two miles apart throughout the Incan Empire that stretched across the Andes Mountains from modern-day Colombia to Chile. Messages could be relayed at the pace of 240 miles a day. Thus it took only five days for a message to travel 1200 mountain miles between 375 runners from Cuzco to Quito. Lima to Quito took four days, a distance of about 1000 miles, at altitudes above 10,000 feet.

In one of the most famous examples of the chaski messenger’s speed and efficiency, fish could be harvested in the coastal village of Chala and hand delivered to the Incan aristocracy in Cuzco, about 450 miles away up the steep slopes of the Andean mountains, two days later. In other words, mountain rulers in the central Andes were dining on fresh fish in the 15th century.

The Royal Incan Highway

The Incas were consummate road builders. In the middle of the 15th century, they built or improved upon 25,000 miles of roadway through some of the toughest, highest terrain on the planet. Alexander von Humboldt, the German naturalist and explorer, who roamed through much of Latin America in the early 19th century, said, “The roads of the Incas were the most useful and stupendous works ever executed by man.”

The heart of this massive circulating system was the Incan capital at Cuzco, deep in the Andes Mountains of present day Peru. The Qhapac Nan had two main north-south routes: one cutting through Cuzco and the central Andean highlands, the other stretching some 2250 miles along the Pacific coast. In between these primary arteries were hundreds of smaller roads, connecting distant outposts, villages and garrisons within the heart of the empire.

The Incan roads tunneled through massive rocks, ascended steep cliffs with stone staircases and spanned treacherous mountain rivers with rope suspension bridges and, most commonly, were between three and 12 feet wide. Grand stretches of frequently traveled highways were paved with cobbles or flagstones, particularly the roads connecting the high plateaus of modern-day Peru and Ecuador. However, the majority of the roads consisted of flattened dirt, sand or grass, and marked with walls, cairns and wooden posts.

The first eyewitness report of the Incan roads entered history in 1548, when Spanish solider Pedro Cieza de Leon, wrote: “I believe since the history of man, there has been no other account of such grandeur as is to be seen on this road, which passes over deep valleys and lofty mountains, by snowy heights, over falls of water, through the living rock and along the edges of tortuous torrents.”

The Chaski Runners

The chaski runners who relayed messages and expensive trade goods along this vast network were well-respected citizens in a culture that placed a high value on running ability. Part of the Incan ritual transition to manhood involved running races up sacred mountains. Fast runners in the ritual races were recruited as potential chaskis. “These guys were groomed and trained for their role,” says Hugo Mendez, an Incan descendant and one of the founders of Inca Runners (see sidebar), an adventure expedition company that leads trail runners along the Inca Trail in Peru. “They would live and train solely to be chaski messengers. It was an elite group of people with a huge responsibility.”

Active chaski runners served in rotating shifts of 15 days on duty, followed by 15 days off. While on duty, the runners lived in stone huts by the side of the highway stationed at approximate two-mile intervals, where they awaited the call of a conch shell announcing the arrival of a fellow messenger. Chaski runners stationed on busy sections of road must have made the trek many times a day, while those on remote stretches were unlikely to run a message more than several times a week.

The chaski runners delivered many message types, mostly relating to the empire’s business. Dr. Salomon, a professor of anthropology at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, says this typically included “military and policy messages, and information for coordinating rituals.” Therefore, it was crucial that messages were transmitted exactly the same way between each runner.

“The authorities who managed the chaski were strict about the accuracy of messages,” says Mendez. “The chaskis couldn’t mess up.” Punishments were harsh: If you insulted the Royal Inca, or any of the Gods, you were thrown off a cliff. If you were caught stealing, your hands and feet were forfeited. And if you were found guilty of less serious offenses, you could be stoned.

So the chaskis were extra diligent about maintaining the accuracy of their messages. Since the Incans were a pre-literate culture, qhipus were an invaluable tool for conveying numbers. In addition to carrying qhipus, the chaski sometimes carried luxury trade goods, like fine cloth, elaborate jewelry or precious objects on behalf of the Incan aristocracy. And then there were the fish, of course.

The chaski ran barefoot or in simple leather sandals made from llama skins, and wore a loose-fitting white tunic. Sometimes they carried a blanket tied around their back to store food, water and trade goods if necessary. They armed themselves with a sling or a mace. Thanks to the brutal efficiency of the Incan justice system, the roads were relatively safe, but lonely sections attracted bandits and some parts ran through the unpredictable territory of recently conquered tribes.

Running the Incan Highways Today

By the mid-16th century, the Incan communication system had completely fallen apart after the Spanish conquistadors toppled the Incan regime and repeated rebellions and uprisings sent shock waves throughout the former empire. Many of the roads in remote areas quickly sank into disuse and ruin. Thankfully, major highway sections are well preserved today and are now collectively referred to as the “Inca Trail.”

The Inca Trail to Machu Picchu, the most famous Incan ruin site, has become an enormously popular hiking destination. In recent years, several expedition companies have begun marketing the Inca Trail as a destination for trail runners.

This year, for the first time ever, you can run in an official Inca Trail Marathon, which finishes in Machu Picchu. Says race director Erik Rasmussen, “The trail is difficult due to the elevation. It ranges from 8,300 to 13,800 feet at the high point called Dead Woman’s Pass. It is mostly paved ancient Inca pathway—flat stones or brick with steep steps. It passes through geographical zones such as Andean grassland and cloud forest.”

Alternatively, you can take part in a 10-day running expedition along the Inca Trail from Choquequirao, another Incan ruin site, to Machu Picchu, hosted by Inca Runners. This expedition, called the Chaski Adventure, takes place several times throughout the year. The deep mountain setting and historic singletrack trail lends itself perfectly to the sport, with its undulating hills and rotating views of evocative ruins and mountain landscapes.

“The mountains are young and seem to shoot straight toward the heavens, constructing impossibly steep walls and breathtaking vistas,” says Walter Rhein, author of Beyond Birkie Fever, who has run on the Inca Trail. “The air is fresh and pure, and the difficulty of the trail and the altitude make running the trail the type of physical challenge that brings you face to face with what you’re truly made of.”

This article originally appeared in our June 2012 issue.